Seasonal Celebrations

Seasonal festivals and other activities take place throughout the Willamette Valley. Such regular displays of ethnic, occupational, or other folklore identities create windows into the varied cultures of Oregon. Some events are private, reinforcing an internal sense of “us” as a group; others are public displays, offering the broader community an insider’s view of a culture.

Though many think of mainstream American culture as “normal” and thus not “cultural,” all people develop cultural practices and beliefs. New Year’s celebrations on December 31 include parties where many drink to health and resolve to change behaviors. These practices reflect American beliefs in self-improvement and progress—folk beliefs not shared by more fatalistic and less individually oriented cultures.

Asian and Asian American communities reckon the New Year on the lunar calendar. Chinese New Year begins at sunset on the day of the second moon after winter solstice. Families clean house to sweep away bad luck and share sayings, called spring couplets, such as, “May all who come and go from here have good fortune.” A feast of six to twelve courses groans on the tables of homes in Chinatown, where two dancing lions kick off the celebration. These practices reinforce the solidarity of Portland’s Chinese community and also trigger reminders of the struggles Chinese people endured locally and nationally.

Chinese immigrants settled in Oregon early in the 1850s. They established laundries, restaurants, and shops; mined for gold; and worked on the railroad. The Oregon constitution forbade the Chinese from buying or owning land. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, denying citizenship to current residents and forbidding entry to others. Despite these discriminatory laws and practices, Portland’s Chinese community and their cultural practices endured.

The Iu Mien, an ethnic minority group from Laos, celebrates the New Year in February. They wear bright red and black traditional shirts, pants, sashes, and turbans made by hand and embroidered in patterns learned by young girls beginning at about age six. Master artist Khen Chiem Saepham learned to embroider from her grandmother in Laos. Whether her children will learn embroidery or the art of the moua, the doughnut-shaped Mien baby hats, will depend on multiple circumstances. Economics, support from the community, and public arts programs can all influence which traditions endure.

As winter turns toward spring, the Lao community who settled in Oregon after the Vietnam War, gathers at their Buddhist temple or wat in northeast Portland for New Year celebration, Boun Pi Mai. At the Baci ceremony, people sit before the pakhouan (altar) as the maw pawn (religious leader) urges them to forget the past and welcome the good in life. These traditions serve as a vital link for people who have been traumatized by war and relocation, even as they adapt clothing, ceremonies, and foods to new circumstances.

In spring, Nisha Joshi, a vocalist and sitar musician raised in Rajasthan, India, joined other Hindus in the valley to honor the Indian festival of Holi. Begun the day after the first full moon in March, Holi commemorates a legend from Hindu mythology. Celebrated differently in the regions of India, the holiday is marked in the United States by music, dance, and feverish frivolity. Celebrants drench one another with water colored with galal powders. Nisha has taught her daughter, Shivani, to chant shlokas, Sanskrit songs about gods and goddesses, dancing, and raags, a form of North Indian classical music.

At Easter, in the streets of Cornelius, “The Passion of Christ” in St. Alexander’s Parish reenacts the journey of Jesus Christ with the cross. In Woodburn, Russian Old Believers observe the Eastern Orthodox Easter reckoned on the Julian calendar a week later than the Gregorian calendar’s celebration. This community descends from Russian Christians who refused to adapt to Tsar Peter the Great’s modernization efforts in 1741. At the Easter service at midnight, women in traditional long dresses and flowered head scarves join men dressed in handwoven belts made on card-weaving looms. Colors and other features of Old Believer dress changed as the group journeyed through South America to Oregon. Even recent innovations have been internalized as traditional.

In May, the Mexican community affirms the connection of mothers to the central figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Musicians begin at midnight to gather under the windows of friends and family to serenade local women.

Also in the spring is Native American Cultural Awareness Week at Portland State University. Nationally, as Native people move to cities for work, their cultures and folk arts changed, with a strong pan-Indian Nativeness emerging. Portland’s Native American residents may still practice folk arts they learned growing up, but they also create alliances with Native artists from throughout the United States. Storyteller Ed Edmo, a Shoshone-Bannock poet, playwright, performer, and traditional storyteller who lives in Portland, worked as an artist in the schools. Alex Muktoyuk of King Island, Alaska, wrote songs in both English and Inupiaq for his performances in Portland and throughout the Northwest. Linguistic and cultural forms have changed with the context, with many Native American performers educating an large audience. Their cultures are traditional but emergent—adaptive to contemporary circumstances.

Weddings have created other traditions White dresses for brides, throwing bouquets, and other taken-for-granted mainstream cultural rituals are from Greek, Roman, and other European traditions. Brides in the Greek community wear stephanas, a contemporary version of the orange blossom-and-olive-branch Greek crowns. Both stephanas to Latino coronas are reminders of a shared need for beauty in rites of passage. Anthropologist Folk arts associated with rites of passage illuminate the range of creativity in cultural communities.

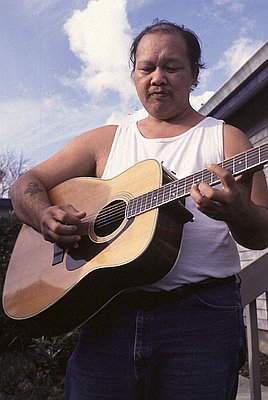

Summer in the Willamette Valley is often a time for outdoor concerts. Sam Kama, a master of the slack-key guitar, grew up up in Honolulu, where he learned a fingerpicking style of playing in which the slacked strings allow for a greater range of sounds. Indigenous Hawaiian arts, including chanting histories and genealogies, have been adapted and changed to incorporate outside influences. Many scholars believe that the guitar arrived in the West with Mexican vaqueros, or horsemen, who came in the nineteenth century to manage cattle. Kama innovates as he transmits his culture to Hawaiians on the mainland who have no other opportunities to learn.

In August, Springfield has a Ukrainian festival, with pysanka (egg dying), icon painting, wreath making, and songs from the Oregon Slavonic Choir. Musicians such as Leonid Nosov play a bayan, a type of accordion, or the harmoshka, a concertina. Nosov’s repertoire has included Ukrainian, Russian, and Moldavian dance and music, all of which he has performed and taught. Many folk artists cross over into other art forms, including styles, and genres. Since coming to Oregon in 1994, Nosov also has written poetry as a way to express the pain and challenges of relocation.

In August, the Homowo Festival takes place in Portland. Ghanian drummer Obo Addy started the festival to recreate an event central to the Ga people of Ghana, the end of the growing season is marked with celebration and thanks. They dance, sing, and cook kpoipoi— a fish, corn meal, and palm oil dish. After a day of feasting comes a fast, during which younger people receive their elders’ blessings and resolve conflicts from the previous year. Valeriana Bandwa has often been part of the festival. She left Angola in 1966, leaving behind her life as a midwife, storyteller, and basketweaver. In Angola, she made baskets with materials from the forest near her home; in Oregon, she uses what is at hand, illustrating both the hardships traditional artists face and the flexible nature of tradition.

The Iu Mien community in Portland calculates the dates for harvest ceremonies according to a strict cultural pattern, the Mien Sixty Year Cycle, or Jaapc Zaangv. A master of this system, Chiem Finh L. Saechao, was born and raised in Laos and moved to Portland in 1981. Because time is cyclical for the Iu Mien, the master of the cycle has to match symbolic meanings from Chinese philosophy to individual lives and group activities, such as planting, and then adapt the cycle again to this new, urban cultural setting.

In Woodburn, one of the oldest Mexican festivals is the Fiesta Mexicana, where there is music, a children’s carnival, soccer matches, and a Miss Mexican pageant. Along with other Latino celebrations like Cinco de Mayo, the festival features mariachi bands and musica norteña—serenatas, corridos, or ballads, and rancheras from northern Mexico. Festivals may also include banda music, born in Sinaloa in the 1930s and popularized in Mexico and the United States in the 1990s. Banda dance styles blend polka and tango, the sounds of big bands, and western dress.

Halloween is a joining of a pre-Christian Celtic festival of the dead with a national holiday. For Celtic peoples, the most important seasonal celebration was Samhain on November 1, when they harvested and stored crops for winter. The Celts lit bonfires and made offerings to the dead, whose souls were believed to return and mingle with the living. Christian missionaries melded this celebration with the Feast of All Soul’s Day on November 1.

Mexico’s El Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, on November 2, is the result of a similar merger, in this case of indigenous Nahuatl and Roman Catholic practices that integrate institutionalized and vernacular cultures. Families clean and sweep the graves of loved ones and create altars with offerings of fruits, sweets, and flowers. Antonio and Bertrand Ramos, traditional woodcarvers from Michoacan, have constructed altars at the Oregon History Center to educate the public about this ancient tradition.

A traditional American Thanksgiving revolves around turkey and football, but other cultures welcome light into the darkest season in other ways. In the Latino community, the feast day of the Virgen de Guadalupe on December 12 marks the onset of the Christmas season, followed by Las Posadas. These folk dramas reenact the search for a birthing place for the infant Jesus. In Cornelius, families dressed as Mary, Joseph, angels, and shepherds go door-to-door recreating the quest for shelter. After nine nights of refusals, the community gathers at Centro Cultural for an evening of food, piñatas, music, and folk theater called la Pastorela, the story of the shepherds’ journey to see the Christ child.

The ancient midwinter tradition of stringing lights on houses has roots in Germanic and English celebrations. In Portland, Fernando Sacdalan has made Filipino Christmas lanterns. The farol, from Spanish for lantern, is a hybrid, fusing Chinese paper traditions with Christian practices brought to the Philippines by the Spanish. Families hung the lanterns in windows during the Christmas season to symbolize the Star of Bethlehem. In Oregon, lanterns now appear at birthday parties and weddings, adapting this form to new settings, often with materials other than paper.

Later in December, Kwanzaa is celebrated—a created tradition whose name is from the Swahili word for “first fruits of the harvest.” African American scholar Maulana Karenga began this pan-African cultural event in the 1960s to celebrate the range of African peoples and cultures in the United States. From December 26, participants honor a different cultural principal each day for a week: unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity, and faith. Lit candles and corn stand for future generations, joining other symbols on the Kwanzaa table. Kwanzaa is a reminder that communities create traditions to meet shifting needs, including political circumstances.

In the Willamette Valley, many different communities are stitched together with folk traditions that are marked by adaptability and resourcefulness, by the expressiveness of people who need to share their values through display and performance. To play the Ukrainian concertina in Springfield or recite the Iu Mien scriptures is to know about dislocation and cultural adaptation. To dance in an urban Indian powwow far from the reservation is to realize the tenacity of tradition and the elasticity of form. To watch the older women at an Iu Mien New Year’s festival, turbans on their heads and sneakers on their feet, is to understand the meaning of a cultural hybrid.

© Joanne B. Mulcahy, 2005. Revised and updated by OHP staff, 2014

Sections

Related Historical Records

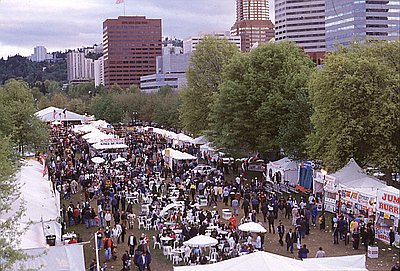

Cinco de Mayo Festival

Portland's Cinco de Mayo Fiesta is held annually at Portland's Tom McCall Waterfront Park and is organized by the Portland Guadalajara Sister City Association (PGSCA). The three-day Fiesta …

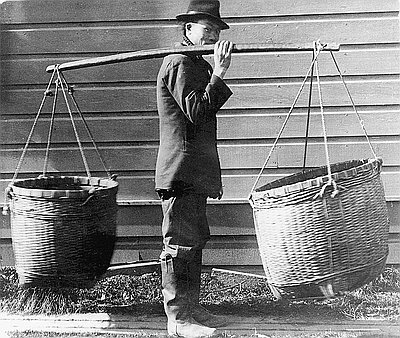

Chinese Street Vendor

This vendor is probably selling vegetables. Chinese gardeners supplied a large proportion of Portland's residents with fresh vegetables. The vendors carried produce through the streets in large baskets …

Hawaiian Slack-Key Guitar

This photograph of Sam Kama was taken in 1995 by Eliza Buck. At the time, Kama was teaching Elroy Aipolani (not shown) how to play “slack-key guitar” through …