The Cascade Range divides the rainbelt of the Willamette Valley from the drier plains and open rangelands of central Oregon. Volcanic activity thousands of years ago left lava caves, pumice deserts, and obsidian flows, a landscape that helps make central Oregon a recreational center. During the summer, windsurfers are on the Columbia River, rock climbers scale Smith Rock outside Redmond, river rafters congregate on the Deschutes; golfers play at the Warm Springs Reservation’s Kah-Nee-Ta Resort, and hikers make their way into the Three Sisters.

Ranching, farming, and other occupations also define central Oregon, and a range of folk arts practitioners appear at festivals between Hood River and southern Deschutes County, including Mexican cooks, bronc riders, cowboy poets, weavers, and quilters. At the Warm Springs Reservation, for example, a root-digging festival and salmon celebration bring outsiders and tribal members together to welcome the land’s abundance. All comprise the cultures of central Oregon.

Hood River, while not properly part of central Oregon, has some of the same cultural and natural features. Windsurfers from all over the world travel to the small town to try their boards on the Columbia River. In the summer, Spanish, French, German, and many other languages are heard downtown cafes, a varied linguistic and cultural heritage that dates to the late nineteenth century when the region had Japanese, Finnish, German, and French farmers and orchard workers. The completion of the Columbia River Highway in 1922 created new possibilities for selling the area’s peaches, apples, cherries, and pears to the rest of the state.

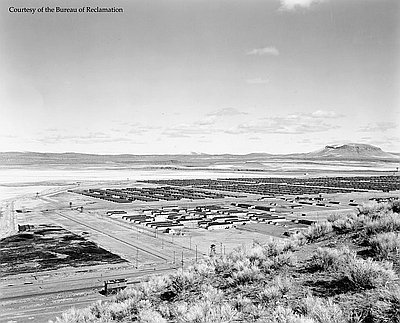

One of the earliest groups of settlers was the Japanese. By 1910, Hood River’s Issei (first generation) population had grown to 468, almost 6 percent of the population. But by 1928, discriminatory land laws and immigration restrictions had reduced Oregon’s Japanese population by 30 percent. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which forced 120,000 Japanese Americans from West Coast states to ten concentration camps inland. Most of Hood River’s Japanese residents were sent to the Tule Lake War Relocation Authority Camp in northern California. Returning to Hood River, many were turned away with signs on local businesses reading “No Jap Trade Wanted.” The Hood River Issei, by Linda Tamura (1993), Stubborn Twig, by Lauren Kessler (1993), and other works document these events, but for years such stories circulated as oral tradition—narratives shaped within a community.

In the twenty-first century, Hood River’s multicultural folklife enlivens local celebrations, and many festivals merge folk and more popular arts for tourists. The Apple Valley’s Quilts on the River celebration, for example, features the work of area quilters who use many traditional patterns, including Trip around the World, Log Cabin, Birds in the Air, Crazy Quilt, and Flying Geese. The crafts also include Father Christmas dolls, weaving, and craft-show items that are not handed down intergenerationally. Folk and popular arts mingle, drawing communities together out of economic need as well as celebratory impulse or cultural tradition.

If folk arts exist on a continuum, a festival quilt whose design was handed down from mother to daughter might inhabit one end, while more idiosyncratic arts rest at the other. One example is the striking tile mosaic work created by Hood River residents Julia Zweerts Brownfoot and her Dutch husband Arnold Zweerts, who adorned their house and garden with mosaics of people from different cultures, brilliantly colored birds, and other aspects of nature. Folk artists carry on traditions making use of existing materials, but they also innovate on what others have taught them.

On the Warm Springs Reservation, traditional dance groups practice for powwows, language revival programs teach Kiksht (an upper Chinookan dialect also known as Wasco), and ritual specialists weave traditional tule mats for longhouse funerals. Wasco, Warm Springs, and Paiute peoples comprise the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation. The Chinookan-speaking Wasco people and the Sahaptin-speaking Warm Springs tribes are both Plateau cultures, joining historically at the sacred fishing grounds at Celilo Falls. Faced with incursions by whites in the mid-nineteenth century, they negotiated their land—one-sixth of modern-day Oregon—for a reservation between the Deschutes River and the Cascades. The Paiutes joined them in the 1880s, after being forced from their homelands in southeast Oregon after the Bannock War and relocated to Fort Simcoe and Fort Vancouver in Washington. Upon release, some Paiutes returned to Harney and Malheur counties, but others settled with the Warm Springs and Wasco peoples.

Many artists have successfully kept the balance between tradition and modernity. Warm Springs poet Elizabeth Woody is also an accomplished painter and printmaker who exhibits regionally and nationally. She apprenticed through the Oregon Folklife Program to learn basket weaving from master artist Margaret Jim-Pennah. Woody’s aunt, Lillian Pitt, is internationally known for her jewelry, ceramic masks, and raku pottery. Both women are firmly rooted in their heritage.

Roma Cartney, a master of Indian foods, has passed on her frybread recipes to young people on the reservation teaches traditional root-digging and berry gathering and preparation. Tony “Big Rat” Suppah and his wife Lucille taught traditional music for many years through the Spotted Eagle Dance and Drum Group. The Warm Springs schools partnered with the University of Oregon’s Northwest Indigenous Language Institute and are now teaching Kiksht, Ichishkiin Snwit (a Sahaptin dialect), and Numu (a Numic dialect). Taaw-lee-winch (formerly Larry Dick) has performed naming ceremonies for others and has made tule mats that line longhouses for funerals and other rites of passage. He has taught medicine singing and the making of deer hoof rattles used for healing ceremonies.

The 2010 census recorded 53,203 American Indians and Alaska Natives in Oregon, 1.4 percent of the state population. Jefferson and Wasco counties, which include a portion of the Warm Springs Reservation, have the highest percentage of Indian residents among Oregon counties (18.4 percent and 4.5 percent, respectively).

The Jefferson County Fair is a sensory multicultural world that links the Warm Springs Reservation, the agricultural traditions of the region, and a growing Mexican population. The region’s economic base of logging, cattle ranching, and hay, grain, and potato farming is linked to the folk arts of Oregon’s pioneer heritage—quilting, leather work, saddle and tack art, wood crafts, and metal work. At the fair, Dan and Joyce Fearrier, both steeped in cowboy culture, exhibit their fine rawhide work, including traditional four-plait riatas and miniature horseshoes of braided rawhide,. Manuela Nuñez Wickham cook homemade tortilla, something she learned during her childhood in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. She decided long ago, she said, that “this is what I want for my kids.” Margarita Chavez of Madras is similarly committed to keeping her Mexican traditions from Michoacan alive through cross-stitch embroidering as well as “pulled thread” crochet work.

In Prineville, Keith Appling has perfected his whittling of flowers, picture frames, balls-in-cages, and other wooden toys. Appling learned to whittle from his father, when carving competitions were part of the family’s entertainment. He carves as an outlet for his creativity, to solve puzzles in wood, and to respond to material surroundings. Folklorist Steve Siporin has written that whittlers are often middle-aged or older men who learned as children, then carried into adulthood “the challenges, the secrets, the puzzles to be solved in demonstrating adult skills.”

Prineville was also home to renowned horseman John Sharp. Sharp grew up riding and training horses on a farm in Oklahoma, arriving in Oregon on a freight train in 1932. During years of ranch work, he developed a skill called “fishing” with a twelve-foot bamboo pole to place horses in 24-by-24-foot pens. With a grant from the Oregon Folklife Program in 2001, Sharp taught Prineville local Dory Howell “how to gentle and tame a wild horse,” an essential transference of folk knowledge from one generation to the next.

In his memoir, New Era, about growing up in Madras, writer and scholar Jarold Ramsey asked how these arts and practices will survive alongside the region’s rapid growth and changing land use. The town is still farm country, green with irrigated fields of sugar beets, carrots, flower seeds, wheat, potatoes, and other crops, but in the twenty-first century developers vie with family farmers and urbanites have taken the place of the rural population.

In Redmond, the population has grown by more than 50 percent since 1990, with tourism and recreation outpacing other forms of development. Off Highway 26, the most visible folk group consists of climbers headed for Smith Rocks, a cultural community marked by shared values, beliefs, and practices. While climbers use highly technical equipment—and discussions of the best materials form part of their lore—they also jerry rig and improvise in ways that qualify as folklife. Climbers also share information through informal networks. Some climbing enthusiasts worry that as the sport grows, it will lose the special nature of this committed group of athletes.

Veteran Redmond bootmaker D.W. Frommer II is exemplary of an artist who carries on a traditional art, but whose less-than-traditional client base reflects changes to the area. Traditional bootmaking begins with a measurement of the foot and building of a “last” or model. Then the leather is cut and sewn, and the boots are finished with stretching the material on a crimping form. Frommer does not use nails, plastic, or paper, and he tans the leather using traditional methods.

Traditional ranching cultures to endure continue in and around Bend. In nearby Alfalfa, Carl Elmer has made saddles since he apprenticed at Portland’s George Lawrence saddlery in 1942, and he ran his own shop in John Day. An Elmer saddle is completely hand-made, from the “tree,” or inner structure, to the stampwork on the exterior—the signature of the saddlemaker.

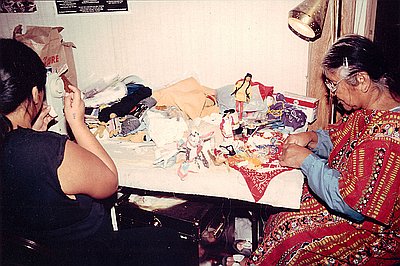

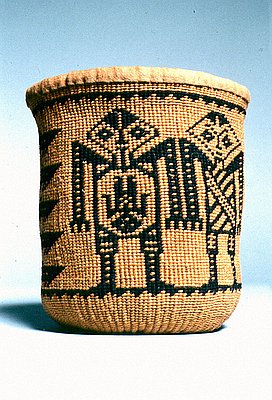

The nature of folk traditions is that of constant change and interplay between so-called outsiders and insiders in preserving and interpreting culture. Dell Hymes, a linguist, folklorist, anthropologist, and native Oregonian, spent years mining the structure of stories from Warm Springs Indians for their ethnopoetic qualities. His translations have brought literary attention to the repertoire of storytellers such as Chinookan speaker Victoria Howard. While doing research at the Smithsonian, non-Native basketmaker Mary D. Schlick rediscovered a rare form of Wasco full-turn weaving. With a grant from the Oregon Folklife Program, she taught weaving to three Native Americans, among them, Pat Courtney Gold, now a master artist. Some of Gold’s baskets tell stories of traditional life; others, such as the deformed “Hanford Nuclear Reservation Sturgeon,” call for social change. Mary Schlick and Pat Gold collaborated to preserve a particular heritage and to create new forms adaptable to social circumstances.

Sometimes, cultural insiders use folk art forms to comment on the dominant culture of the collector. Jarold Ramsey compiled and interpreted Indian trickster tales in Coyote Was Going There. In one example, excerpted in The Stories We Tell, edited by Ramsey and folklorist Suzi Jones, Coyote tricks a visiting anthropologist. The scholar frees Coyote from a trap after the wily animal promises to tell him a “real true story, a real long one for your books.” Later, when the anthropologist tries to play the taped story for his academic colleagues, “all that was in the machine was a pile of coyote droppings.”

Collaboration, change, cross-fertilization—all are as critical as preservation. In central Oregon, the dynamic mix of cultures is evident in the smell of tortillas mixed with Indian frybread, in the brilliantly colored quilts hanging alongside the masonry of Julia Zweerts Brownfoot, and in the climbers and ranchers who share tables in a Bend coffeehouse.

© Joanne B. Mulcahy, 2005. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014