The Exposition and Native Americans

On the 1905 fair grounds, the most prominent presence of Native Americans was inanimate—the bronze statue of Sacagawea that would later stand in Portland’s Washington Park. The Indian exhibit in the Government Building, put together by the U.S. commissioner of Indian affairs, was largely devoted to the training programs at government-run schools like Chemawa in Salem and to products manufactured by students in manual arts classes such as the blacksmith work from Warm Springs or the buggy harness, tools, and wagon from Chemawa. “This is the first exhibition of Indian work made on the Pacific Coast where the general public have had the opportunity of examining the character of the training given people in the Government Indian schools,” said the official program.

A century had wrought a drastic change, transforming the everyday inhabitants of western Oregon into an exotic group of “others” and a “problem” whom the fair organizers treated as a topic of formal discussion at a Conference on Indian Affairs and a Pacific Coast Institute that brought together staff from the various Indian schools. The papers and discussion at the Institute concerned practical issues of school administration and curriculum. Portland housewives might have been happy to learn from the Institute that Indian girls could be trained as “neat and capable housekeepers” for upper-class families.

The situation had been different a century earlier. Between Celilo Falls—above The Dalles—and the mouth of the Columbia, speakers of Chinookandialects dotted the river islands and entry points of small rivers and streams. Their “metropolis” was Sauvie Island and the adjacent Oregon shore, a scant ten miles from the future fairgrounds. Lewis and Clark counted 2,400 people on the island and 1,800 along the south side of Multnomah Channel. Six years later, British fur trader Robert Stuart reported a population of about 2,000 on the island itself—a denser population than the island supports today. There were perhaps fifteen separate villages on Sauvie Island and immediately adjacent areas. Residents fished for salmon, sturgeon, and smelt; hunted migratory birds and deer; gathered nuts and berries; and dug wapato roots along the rivers. “Wappato Island” was Lewis and Clark’s name for Sauvie Island. Cedar logs provided materials for canoes, cooking utensils, and longhouses. Villages were built to last for years rather than decades, for the abundance of natural resources made it easy for a group to move from one spot to another within its general territory.

In contrast to their bustling settlements along the Columbia, Native Americans made only limited use of the lower Willamette River. Not until they reached the Clackamas River and the Willamette River falls, twenty-five miles upstream, did European explorers find more than scattered and often temporary settlements. Here, where the salmon stopped, the natural environment again made life relatively easy for the Cushook, Chahcowah, and Clackamas peoples. The falls were a point of contact between maritime groups and hunting peoples of the Tualatin Valley. Twenty or so small villages of Tualatin Indians used the valley, traded with river people, and occasionally gathered near Gaston. They were a subgroup of the Kalapuyas of the central Willamette Valley, all of whom had learned to improve their environment with periodic fires. Their purpose, they told naturalist David Douglas, was to clear the land for ease of gathering wild foods and to force deer into areas where they were easy to hunt.

The growing presence of white traders introduced a very different change in the natural environment that now destroyed the Native Americans whom it had nurtured. Among the world's most isolated peoples, the Indians of the Northwest Coast were easily susceptible to new diseases that arrived with Europeans. Smallpox came upriver in the 1770s, 1801-1802, and 1824-1825. In 1830, the “Cold Sick” or “Intermitting Fever” appeared in Chinook and Kalapuya villages. It raged for the next three years along the Willamette and lower Columbia. It is likely that the disease was malaria brought from the tropical Pacific by traders. Whatever its true identity, the Cold Sick spread outward from an infection epicenter at Sauvie Island and Fort Vancouver. It killed half in some villages, 90 percent in others, leaving a few hundred Native Americans and a virtually unoccupied Willamette Valley landscape for the English-speaking settlers who began to arrive over the Oregon Trail in the 1840s. By 1905, the few thousand survivors of plague and war were squeezed onto reservations east of the Cascades and scattered near the coast.

© Carl Abbott, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

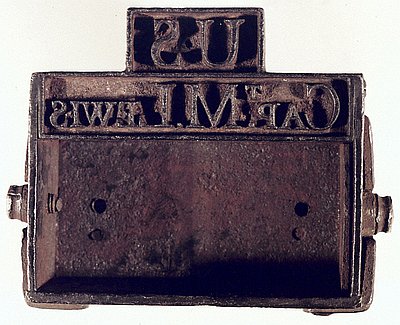

Captain Meriwether Lewis's Branding Iron

Captain Meriwether Lewis carried this branding iron on the Corps of Discovery’s 1804–1806 exploration of western North America (the captains also carried a smaller "stirrup iron" used to …

Dalles of the Columbia, 1805

This roughly sketched map labeled Dalles of the Columbia, with camps of October 26-28, 1805, depicts the area from Celilo Falls downstream to the Klickitat River. It was …

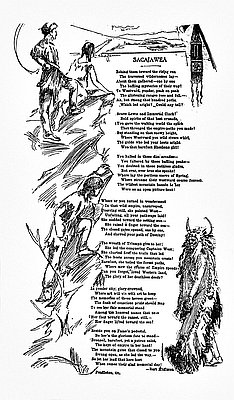

Ode to Sacajawea (Sacagawea)

Click here for transcript. This poem, by Bert Huffman of Pendleton, was probably written in commemoration of a bronze statue of Sacagawea (Agaideka Shoshones spell it "Sacajawea"; the …