The Booster City and Business Leaders

Portland started the twentieth century with a flourish of self-promotion. After a half century as the most important city in the Pacific Northwest, Portlanders were looking nervously toward the pushy new cities on Puget Sound, Bellingham, Seattle, and Tacoma. While Portland businesses still struggled with the aftereffects of the financial panic of 1893, Seattle boomed as the staging point for the Klondike gold rush. The response of the Portland business community was to reassert the city’s importance, publicize its commercial advantages, and boost its future growth to every available audience. The Lewis and Clark Exposition was simply the most spectacular example in this revival of Portland boosterism.

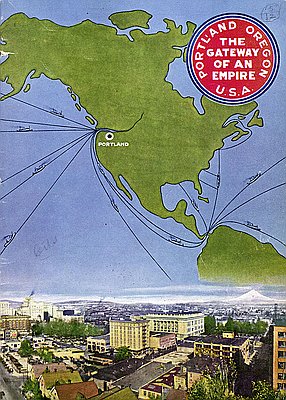

The central theme in Portland’s self-portrait was the claim to be the natural metropolis of the northern Pacific Coast. The Oregonian was extremely pleased that Seattle had fallen 10,000 short of Portland’s population in 1900 and asserted through the next decade that Portland was more than holding its lead. Many residents assumed that the preeminence of Portland in the industrial life of the Northwest was beyond debate. In particular, the city’s bankers and wholesalers dominated the financial life of Oregon and Washington. It was not merely a “neighborhood center,” Albert Holman told the readers of World’s Work, but a city like Atlanta, New Orleans, St. Paul, or San Francisco that served as the metropolis of an entire region. “There is no place in the world where the optimist has more chances of realizing his greatest dreams,” added editor William Wells of Portland’s Pacific Monthly.

Future growth for the city seemed assured by its location, for Portland was the natural gateway between the growing agriculture of the Columbia Basin and the vast markets of East Asia and Latin America. Time and again Portlanders talked about the products of forest and field, about lumber and grain. They pointed to the water level route to the interior which supposedly assured their success over Seattle and Tacoma and to the new twenty-seven-foot channel to the Pacific. The illustration of choice for most articles in the early years of the twentieth century was a photograph looking north from the Steel Bridge over a harbor crowded with rafts of logs and dozens of grain ships. The conclusion was simple for those who read the future from the landscape: Portland was “chosen by a decree of fate, which inertia, obstinacy or folly may postpone, but never alter.”

The Lewis and Clark Exposition drew on the same leadership as other booster efforts in the new century. The first serious efforts came from Joel .M. Long of the Portland Board of Trade, who put together a provisional committee that met occasionally during the second half of 1900 to consider a Northwest Industrial Exposition. The date and the theme came from the Oregon Historical Society. Meeting under the leadership of Oregonian editor Harvey Scott on December 15, 1900, the society endorsed the suggestion for a commercial exposition to be held in conjunction with the centennial of Lewis and Clark’s exploration of the Oregon Country. Two months later, the Oregon legislature endorsed the Oregon Historical Society’s suggestion, pledged state aid once an effort was organized, and appointed five commissioners to report on progress to the next session. The chairman was Henry W. Corbett, president of the First National Bank, former United States senator, and the city’s leading businessman.

Official participation by the state of Oregon was a foregone conclusion. Portlanders were careful to point out that the fair was designed to attract attention to the entire state for “the development of our material resources and manufacturing interests,” and the legislature acted early in 1903 to appropriate $450,000 for an exhibition of Oregon’s “arts, industries, manufactures, and products.” To oversee the state effort, the legislators established a Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition Commission. The commission was tasked with organizing, promoting, and managing the Exposition. It was to pay for many of the necessary buildings, obtain state and county exhibits, and keep an eye on the businessmen who were running the show in Portland. The result, said the people’s representatives in the rolling language of public bodies, would benefit the people of the state “by way of the advertisement and development of the agricultural, horticultural, mineral, lumber, manufacturing, shipping, educational, and other resources of said state.”

The first hurdle for the private corporation that Portland’s elite set up to stage the event was to persuade other state legislatures and congressional committees to share the costs of yet another fair in a small, aspiring city. During 1903 the corporation dispatched five special agents to stalk the corridors of western capitols and cadge votes in the nearby barrooms. At year’s end, lobbyists reported success in Sacramento, Boise, Salt Lake, Helena, Bismarck, St. Paul, and Jefferson City.

Sixteen states came through with appropriations for exhibits before the fair opened, and ten constructed special buildings. Maine, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Illinois erected modest exhibit buildings. Missouri, Massachusetts, and New York built larger structures to match their population and importance. Washington and California took advantage of the opportunity offered by the first western exposition with buildings that rivaled some of the main halls.

The focus on economic development set the theme for the more difficult lobbying job in Washington, D.C., in the winter of 1903-1904. No one in Congress had much interest in the historical heroes and their two-thousand-mile trek. But they did share the same vision of Pacific trade that had motivated the exploration and settlement of the Oregon Country. Oregonians pushed the idea that a Portland fair was “an undertaking of national interest and importance.” With help from the Washington and California delegations in Congress, they argued successfully that the Exposition was a Pacific Coast enterprise with support stretching from San Diego to Spokane.

© Carl Abbott, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

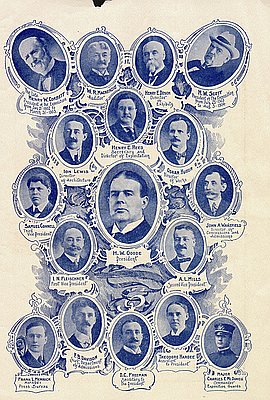

Exposition Company Leaders

This image, showing the directors and officers of the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, is from the fair’s “Portland Day” program. The officers were mostly local businessmen, who …

The Gateway of an Empire

This 1924 booklet promoted Portland as the natural “gateway” for ship trade between the Pacific Northwest “empire” and markets on the East Coast and in foreign countries. The inside cover asserted that “The …