When the last visitor walked out the gates on October 15, Portlanders could be especially satisfied at the impression that the city and its extravaganza made on visitors. Leslie’s Weekly described “the latest great exposition” as “Portland’s pride.” Walter Hines Page summarized the consensus when he told eastern readers that “'the enterprise has from the beginning been managed with modesty, good sense, and good taste.” The first notices in Portland were just as glowing. The Oregonian and the Pacific Monthly marked the closing day with editorial tributes to enthusiasm and regional cooperation.

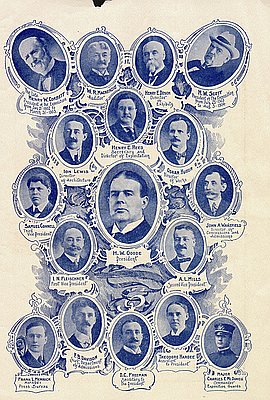

A year’s reflection did nothing to change the belief that “the Lewis and Clark Exposition was a great thing for Oregon.” Oregonian reporters interviewed George Chamberlain, Henry W. Goode, Willis Nash of the Board of Trade, and other leading citizens in October 1906. To the man, they shared the paper’s editorial opinion that “the Lewis and Clark Exposition officially marked the end of the old and the beginning of the new Oregon.” Portland and its sister cities of the Northwest, said Richardson, had “caught step in the great march of progress.”

After half a decade, Portlanders were still satisfied. “It seems that confidence came with the Exposition,” wrote C.H. Williams of the Commercial Club in the Banker’s Magazine. On a return visit in 1913, former vice president Charles Fairbanks marveled over the new skyscrapers built since his opening-day visit in 1905 and told a reporter from the Telegram, “No place that I know of has made such remarkable development and progress.” Portland historian Joseph Gaston summed up the consensus in 1911:

The very decision to hold the exposition, strengthened every man that put down a dollar for it; and from that very day Portland business, Portland real estate, and Portland’s great future commenced move up—to move with confidence, courage, steadfastness, accelerating energy; and the movement never halted or hesitated from that day to this. The exposition . . . attracted hundreds of thousands of people, many of them wealthy, to this city, who knew nothing of the advantages of Portland and its surroundings. They were surprised and pleased at what they found and learned, and went away to spread the story of Portland's beauty and future prospects, and then came back to invest their money in Portland property and business.

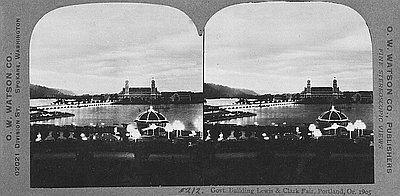

The fairgrounds themselves, however, had a less glamorous future. The Exposition company had leased rather than purchased the site, and constructed buildings that were not intended to last. Most of the buildings were demolished within five years, and only the massive Forestry Building survived to the 1960s before burning in a spectacular fire. The lake itself was filled in the 1910s and 1920s with dirt sluiced off the West Hills (to make the streets and building lots of Westover Terrace) and mud dredged out of the Willamette as the Port of Portland deepened the channel. The fill dried and settled in the 1930s and was ready for industrial buildings in the 1940s and 1950s.

At the Lewis and Clark Exposition, Oregon staked a claim on the future. As the first world’s fair on the West Coast, its success sent a simple message: Despite upstarts like Seattle and Los Angeles, Portland was still a place to be reckoned with. It was cultured and civilized and as up-to-date as electricity could make it. The exhibits and activities elaborated on the theme. Oregon had grown by harvesting its natural bounty from forests, fields, and rivers for national and international markets. In the coming decades, Oregonians hoped to produce more and more and sell its products more and more widely around the rim of the Pacific Ocean.

Much of that vision came to pass. Oregon did continue to develop through farming and forestry, which remained the state's dominant industries through much of the twentieth century. The Pacific vision did not work out quite as planned, but shipbuilding for the great war with Japan from 1941 to 1945, a new role in the 1980s and 1990s as a major port for the importing of Japanese and Korean automobiles, and Asian investment in Oregon electronics factories all forged unexpected ties to the Pacific economy.

As Oregon commemorates the two-hundredth anniversary of Lewis and Clark’s transcontinental trek, the question and challenge is to understand the changing balance of old and new. The older Oregon of 1905 still shapes attitudes and opportunities in many parts of the state. But nearly every corner also shows traces of a “new” West that is networked in ways that would have astonished—and probably delighted—the boosters of 1905. The examples range from European windsurfers in Hood River to new information companies benefiting from new Internet connections in Burns to nationally known art businesses in Joseph to trans-Pacific fiber optic cable landings on the coast. Just as Oregonians in 1905 wanted to keep what they had accomplished as a base for the twentieth century, the test for today is to maintain the best of the last hundred years as the springboard for a sustainable future.

From Two Centuries of Lewis and Clark: Reflections on the Voyage of Discovery, by William L. Lang and Carl Abbott. Published in 2004 by the Oregon Historical Society Press. © Oregon Historical Society Press. Revised and updated for this OHP narrative.