Clark, Pomp, York, and Sacagawea

Statue of William Clark's slave York, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806. The statue is installed in Louisville, Kentucky.

Unlike Lewis, Clark lived into his sixties and played an important role in the development of the Louisiana Territory, including investment in one of the first fur companies to work the upper Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. By 1813, Clark had become governor of the newly created Missouri Territory, a position he held for three terms until Missouri achieved statehood in 1820.

During his years in St. Louis, Clark remained connected to several members of the Corps. Although he had said farewell to Sacagawea and Charbonneau at the Mandan Villages in 1806, Clark had offered to care for Jean Baptiste and provide him with an education. By 1809, his parents had come to St. Louis and handed over Pomp (Clark’s nickname for the child) to the care of a man who presided over governmental relations with Indian tribes for the entire region. Clark fulfilled his promise, providing for Pomp’s nurturing and enrolling him, for a time at least, in a St. Louis school. As a young man, Pomp worked in the fur trade business and spent time as a guest of Prince Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg in southern Germany in the late 1820s. He returned to America in 1829, re-entered the fur trade, and eventually participated in western gold rushes until his death in southeastern Oregon in 1866.

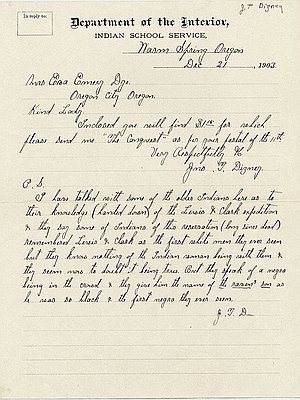

For many years, historians believed that Clark had freed Yorkafter the Corps returned to St. Louis. References to Yorkin the Expedition documents emphasize his reception by Indians along the route and his service to his master, but there is no indication that Clark planned to manumit York after the Expedition. Nonetheless, Washington Irving reported in the 1830s that Clark had freed York, but a letter between Clark and his brother makes it clear that York remained his slave until at least 1810. Whether Clark ever freed York is unclear. York does not appear on a list of Corps members that Clark recorded in the mid-1820s. Some sources have York engaged in the fur trade on the Missouri or living with Crow Indians well into his late sixties. As an intriguing figure from the Expedition, York has achieved heroic stature among historians who have rescued the African American past from obscurity.

Sacagawea also has a contested biography. According to most historians, she continued to live with Charbonneau, had a second child, daughter Lissete, and died of fever at Fort Manuel on the Missouri in December 1812. An alternative biography, however, has Sacagawea living with Charbonneau until about 1820, when she left him because he took another wife. According to oral histories taken on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming, Sacagawea lived out her life among the Shoshone, where she was known as Porivo. In this biography, she lived until 1884 and recounted many times how she had gone to the Pacific Coast with Lewis and Clark. The documentary sources of her death on the Missouri in 1812 are more immediate to the era and Clark appears to have accepted trader John Luttig’s report of her death.

Regardless of the truth of these contradictory stories, Sacagawea has become one of the most recognized figures from the Expedition story. By the end of twentieth century, she had become an icon for women’s rights movements, her fame had created statues in her honor in several states, and her image became only the second picture of a female to be used on U.S. currency. For others, Sacagawea stands as a symbol of the Expedition’s non-aggressive purposes and successes in Indian relations, an interpretation that generates as much controversy and discussion as the correct spelling of her name and the true date of her death.

© William L. Lang, 2004. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.