The Coastal Lumber Industry

It was clear by the last decades of the nineteenth century how logging was altering the coastal landscape. In 1872, writer Frances Fuller Victor visited the renascent town of Astoria, which had between four and five hundred inhabitants. Describing Smith Point, the site of the old Fort Astoria, she wrote:“The whole point was originally covered with heavy timber, which came quite down to high-water mark; and whatever there is unlovely in the present aspect of Astoria arises from the roughness always attendant upon the clearing up of timbered lands.” If a person were to look out toward the river, she continued, “with your back to half-cleared lots, made unsightly by the blackened stumps of trees, the view is one of unsurpassed beauty.”

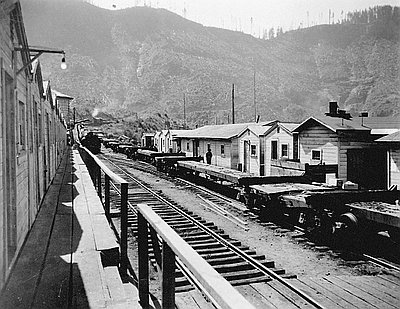

After a decade-long heyday in the 1880s, the cargo mills like those started by Asa Simpson on Coos Bay were gradually supplanted by bigger mills, as rail and steamships began to favor locations that could serve as both railheads and ports for large ships. At the same time, innovations in milling technology demanded expensive upgrades that drove smaller operators out of business. Technical innovations in the woods, such as the logging railroad, the steam donkey, and the two-man crosscut saw, were greatly improving efficiency in logging and quickening the pace of cutting in the hills around coastal communities.

Also during the 1880s and 1890s, the choice timber pickings in the West were attracting midwestern lumber barons like Frederick Weyerhaeuser of St. Paul, D.A. Blodgett of Grand Rapids, and Charles Stimson of Muskegon. These entrepreneurs came to the Pacific Coast from the exhausted pine forests of Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin with deep pockets of capital, looking for “other worlds to conquer,” in the words of an 1898 article in the Coos Bay News.

One lumberman, Charles Axel Smith, left an indelible mark on the landscape and communities around Coos Bay. Born in 1852 in Östergötland, Sweden, Smith had immigrated to the United States in 1867 and settled in Minneapolis. As a student at the University of Minnesota (or, as another story has it, as a hardware store clerk), he met John S. Pillsbury, governor of Minnesota and a member of the well-known flour-milling family. Pillsbury became Smith’s mentor and eventually his business partner.

Smith made several discreet trips to the West Coast in search of timber. To keep competitors from divining his intentions, he traveled incognito and worked through anonymous agents who scouted the region for the richest stands. In this way he acquired thousands of acres of Douglas-fir and redwood, some of it by illegal means. He also picked up thirty thousand acres of timberland from E.B. Dean and Co., along with their logging railroads and Marshfield mill facilities.

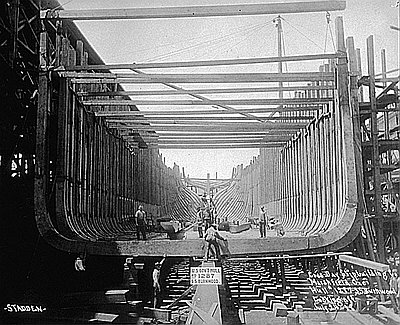

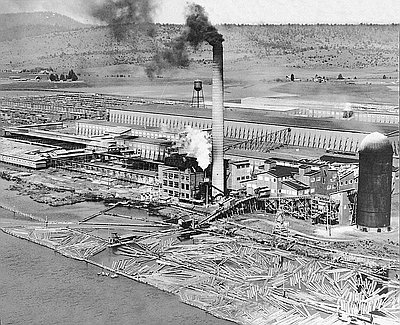

In 1907, Smith built a state-of-the-art sawmill on the tide flats of the upper bay and brought in Scandinavian workers—Swedish and Finnish millwrights, machinists, blacksmiths, mechanics, sawyers, edgers, trimmers, planers, greenchain-pullers, and water boys—to build and operate his Big Mill, as it came to be called. With his Oregon partner Albert Powers, Smith operated seven logging camps along the wooded tributaries to Coos Bay. By 1920, about half the loggers and sawmill workers on Coos Bay worked for him.

Smith took pride in pioneering the most efficient milling technology and the most enlightened forestry practices of the day. He and Powers brought in trained foresters to start a reforestation program. They invited Carl Alvin Schenk, the director of the Biltmore School of Forestry and a leader in scientific forest management, to bring his students on field trips to learn from Smith’s operations. He was one of several turn-of-the century entrepreneurs who transformed the timber economy on the West Coast into a highly capitalized, technology-heavy business. The Big Mill dominated lumber production on Coos Bay for almost fifty years; and although Smith never lived permanently there, he left an indelible stamp on Coos Bay’s landscape and communities.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Weyerhaeuser Timber Company

At the time of this photo in 1941, Weyerhaeuser Klamath Falls employed approximately 1,200 men and produced 200 million feet of wood products each year. Weyerhaeuser experienced a …

Scandinavian Immigration

This undated photograph of a group in Scandinavian costumes was taken in Portland by a photographer documented only as “Erickson.” Between 1820 and 1920, more than 2.1 million …

Coos Bay Lumber Company Steam Donkeys

The steam donkey, invented in 1880, greatly increased the efficiency of logging operations in Oregon’s forests. It replaced animal labor, which could not work as fast in rainy …