Labor Unrest between the Wars

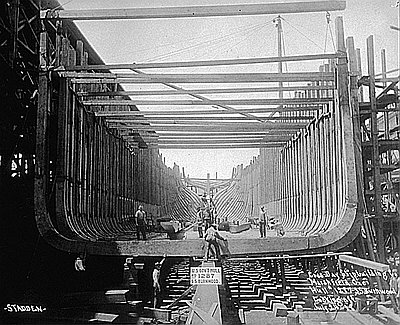

By the end of the 1920s, conditions for workers had improved from those of the days before World War I. The eight-hour day had been almost universally adopted, and other improvements had come with the wartime upswing in the economy. Still, conditions in the mills and woods and along the waterfront were far from ideal.

The Wobbly spirit rose again in 1929 with the formation of the National Lumber Workers Union. The NLWU, which made no secret of its communist sympathies, carried on some of the Wobbly demonstration tactics, but it was unable to bargain effectively with mill owners. By the mid-1930s, however, Roosevelt’s New Deal was making things easier for unions. In particular, collective bargaining had been established as a worker’s right under the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. The Supreme Court struck down that law, but the right of labor to organize was ultimately preserved in other legislation.

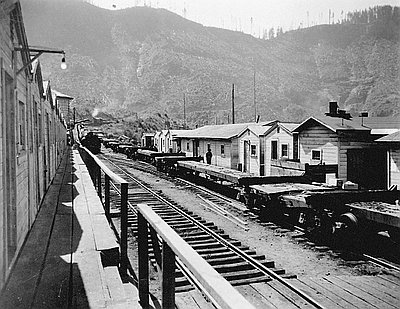

In May 1934, the International Longshoremen’s Union (ILU), affiliated with the AFL, struck West Coast ports. There were a couple of violent incidents when employers tried to bring in nonunion workers from outside and strikers threw rocks at the strikebreaking workers and overturned a bus in Empire, near Coos Bay. The strike ended when waterfront employers and the union agreed to federal mediation. The longshoremen subsequently won considerable concessions from owners, including higher wages, a thirty-hour work week, and less arbitrary hiring procedures.

A strike in 1936 and 1937 led longshoremen along Coos Bay to leave the AFL and form the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union under the Congress of Industrial Organizations. The CIO, which sought to represent workers across an entire industry, was more militant than the craft-based AFL.

As for sawmill workers, in 1935 the weakened NLWU disbanded and encouraged its members to join the Lumber and Sawmill Workers, part of the AFL. The sawmill workers were lumped in with the carpenters, which made some sense in the AFL’s craft-based worldview; in practice, however, the two groups had little in common. A surge of militancy ensued that, fueled by workers’ fears about what would happen to them without the protection of the National Industrial Recovery Act had been overturned, led to a large-scale sawmill strike starting in May that shut down half the mills in the Northwest.

The union demanded first that the owners recognize its right to exist. On top of that, the workers wanted a minimum hourly wage of seventy-five cents (the minimum wage at the time was about forty-five cents an hour in sawmills), a thirty-hour work week, time-and-a-half pay for overtime work, and paid holidays. The strike was resolved in August 1935, with workers gaining a five-cent-an-hour wage increase, a forty-hour work week, and recognition of the AFL in logging camps and sawmills.

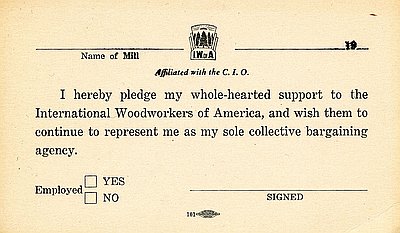

As had happened in the dockworkers’ ranks, the more militant sawmill workers chafed under the yoke of the conservative AFL. Some of them broke away and formed the International Woodworkers Association under the CIO. The two unions fought each other bitterly through 1937 and 1938, leading to disputed strikes, challenged elections, boycotts, plant shutdowns, and standoffs with employers.

In view of the unquiet history of the Northwest labor movement, it is not surprising that union-management and union-union conflict was bitter and sometimes violent during this time. By the late 1930s, however, the environment surrounding management-labor relations had shifted greatly, largely because of the increased federal presence of the New Deal. The federal government mandated minimum wages and collective bargaining, and federal mediation offered a forum for the resolution of disputes when labor-management talks broke down. Federally funded jobs put people to work, and federal assistance programs blunted the sharpest edges of poverty for the unemployed.

Finally, the recognition of the union by sawmill owners indicated an emerging consensus (however reluctant on the part of some owners) that unions had a legitimate role to play in a free-market economy. After further struggles with owners after World War II, Pacific Coast unions embarked on a period of strength and relative stability that would last forty years. Union membership in the twenty-first century continues as a bond of identity among sawmill and dockside workers in Oregon’s coastal towns.

© Gail Wells, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

IWA Membership Card

Shown here is a membership card for the International Woodworkers of America (IWA), a timber workers union. It probably dates to 1937 or 1938, shortly after the union …

The Lumber Strike Wanes

This editorial appeared in the Coos Bay Times on May 29, 1935. It describes the 1935 lumber strike, one of the largest labor strikes in Pacific Northwest history. …