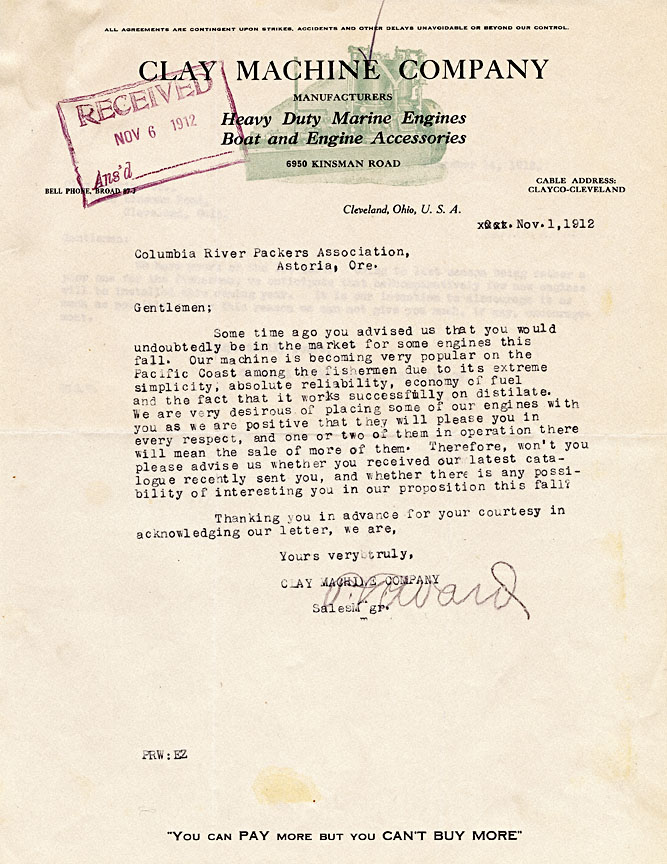

The sales manager for the Clay Machine Company sent the first letter reproduced here to the Columbia River Packers Association (CRPA) in November 1912 hoping to sell engines to the CRPA for use in their fleet of fishing boats. The second letter is from a representative from the CRPA, who responded that the previous fishing season was poor and that they did not anticipate installing many new engines. “It is our intention to discourage it as much as possible,” they concluded. Also included is an advertisement that shows the Clay Machine Company’s engines.

In the late nineteenth century most salmon commercially harvested in the Columbia River were taken by gillnetters who operated small sail- and oar-powered boats. Gillnetters began experimenting with motors in the late 1890s. Although not particularly powerful or reliable by today’s standards, these small engines revolutionized the Columbia River salmon fishery.

Despite the negative response of the CRPA to the first letter reproduced above, Columbia River salmon canneries did install engines on most of their boats over the course of the 1910s. Independent fishermen with motorized boats were able to access areas that the canneries’ sailboats could not, giving them a competitive advantage. Commercial gillnetter and writer Irene Martin notes that “this competition undoubtedly applied pressure to the cannery owners to capitulate and modernize.”

By 1915 one observer noted that “one of the most picturesque sights of the Columbia River as seen from Astoria is when the fishing fleet of three thousand boats start for the fishing grounds. The boats have one large sail and nearly all of them have a gasoline engine.” By 1927, another writer observed, the fishing fleet had lost their sails: “Now they chug along to the popping tune of a gas motor. The beauty is gone, but security and efficiency are there.”

The replacement of sails and oars with gasoline-powered motors changed the way fishermen operated. Gillnetters could move up and down their drifts more swiftly, greatly increasing their daily catch. Many also ventured to different parts of the river to fish, sometimes leading to conflicts over drift rights. The increased mobility of motorized boats also enabled fishermen to venture beyond the Columbia bar out into the ocean where state fishing regulations did not reach. Trolling became a new, controversial method of catching salmon before they returned to the Columbia. The ocean troll fishery increased rapidly during the first half of the twentieth century, eventually eclipsing the in-river gillnet fishery.

Further Reading:

Martin, Irene. Legacy and Testament: The Story of Columbia River Gillnetters. Pullman, Wash., 1994.

Smith, Courtland L. Salmon Fishers of the Columbia. Corvallis, Oreg., 1979.

Taylor, Joseph E., III. Making Salmon: An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis. Seattle, Wash., 1999.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.