|

Oregon women joined millions of women across the country who found meaningful employment in war-related industries. Women who had been restricted to particular jobs—or to no jobs at all because of their gender and race—worked with men in factories and farms The increased democratization of the labor force in the United States during World War II was a consequence of the desperate need for workers to begin working immediately. Because of the draft, which took many men out of the workforce, the tens of thousands of government-contracted jobs that were opened to Oregon women were the highest-paying and often the most interesting jobs most women had ever held. Many women moved to Oregon to take jobs, but most of those who were engaged in war-related employment were already living in the state. By 1943, women made up 65 percent of new hires in Oregon shipyards. Beginning in February of that year, about a thousand workers a week were trading their non-war-related jobs for war-production employment. What happened when these thousands of women exchanged their traditional low-paying unskilled jobs for those that required skills and earned them higher pay? Some women making three dollars a week as domestics were suddenly making up to $230 a month as welders in the shipyards. They had money to spend and could buy houses and farms, pay for college, afford childcare, and influence consumer trends. Federal, state, and local governments could see the cultural shift resulting from the massive labor recruitment campaigns for women workers—a shift that caused anxiety in the male workforce unused to competing with women in the labor market. The War Department responded to that anxiety by distributing propaganda characterizing the return to prewar employment conditions as a patriotic duty. Women enthusiastically engaged in the demographic reorganization of the economy in ways that forced men to see women’s physical and intellectual capabilities and, in many ways, how invested they were in the health and well being of their communities and workplaces. That investment is evident across race, ethnicity, and circumstance, and it endured beyond the end of the war. As women lost their jobs to men returning from the war, they could see the grim realities of a post-war economy that would likely deny them employment as high-paid skilled workers. During the war, many had anticipated the impending female labor purge by joining unions, earning certifications, and forming labor associations. “What will [women] ask in return?” Banning wrote in 1942. “First, I hope they will insist that if they have done well and shown staying power and ability, they suffer no more in the period of readjustment than do men. They should not be penalized or discriminated against as women.” |

|

|

|

|

The Hermina Strmiska papers |

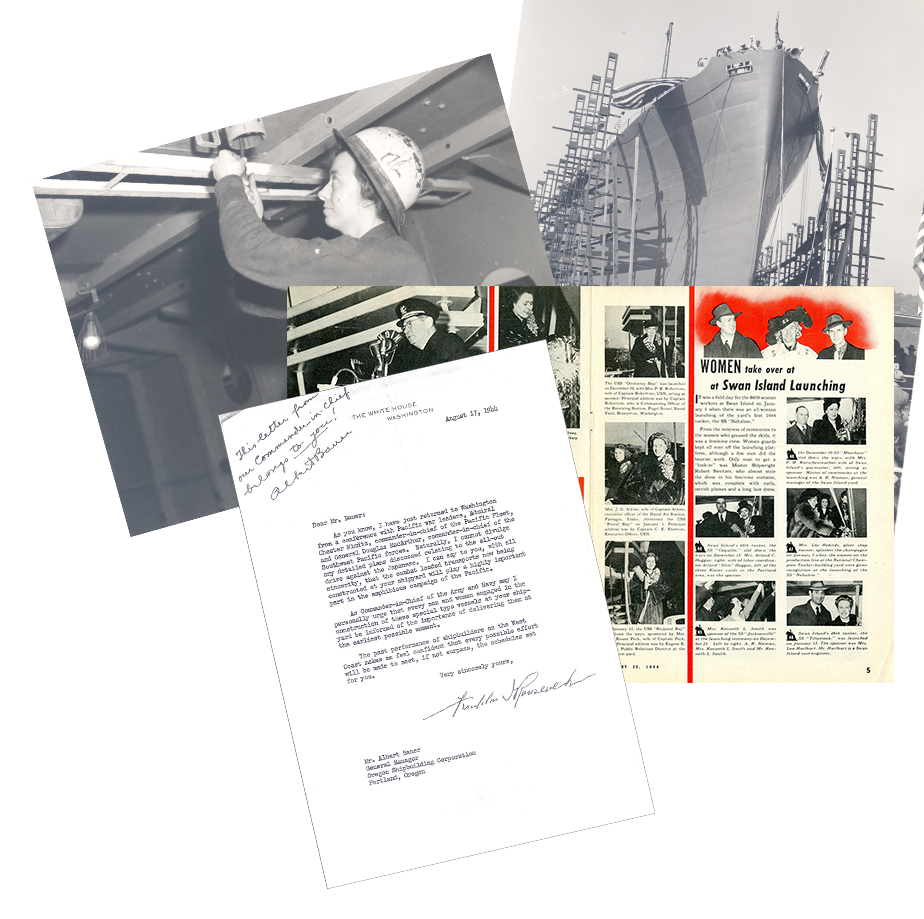

The Launching of the S.S. Nehalem |

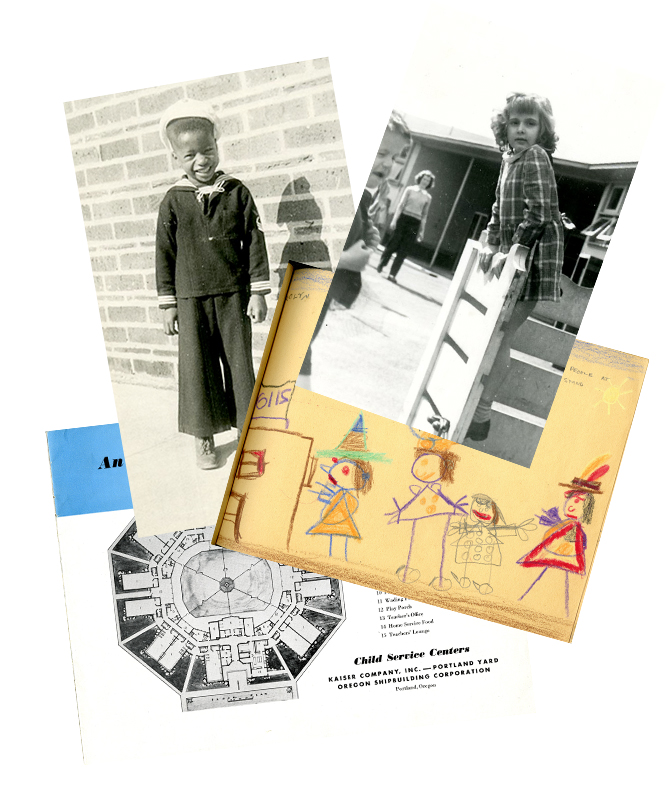

Swan Island Child Services Center |

|

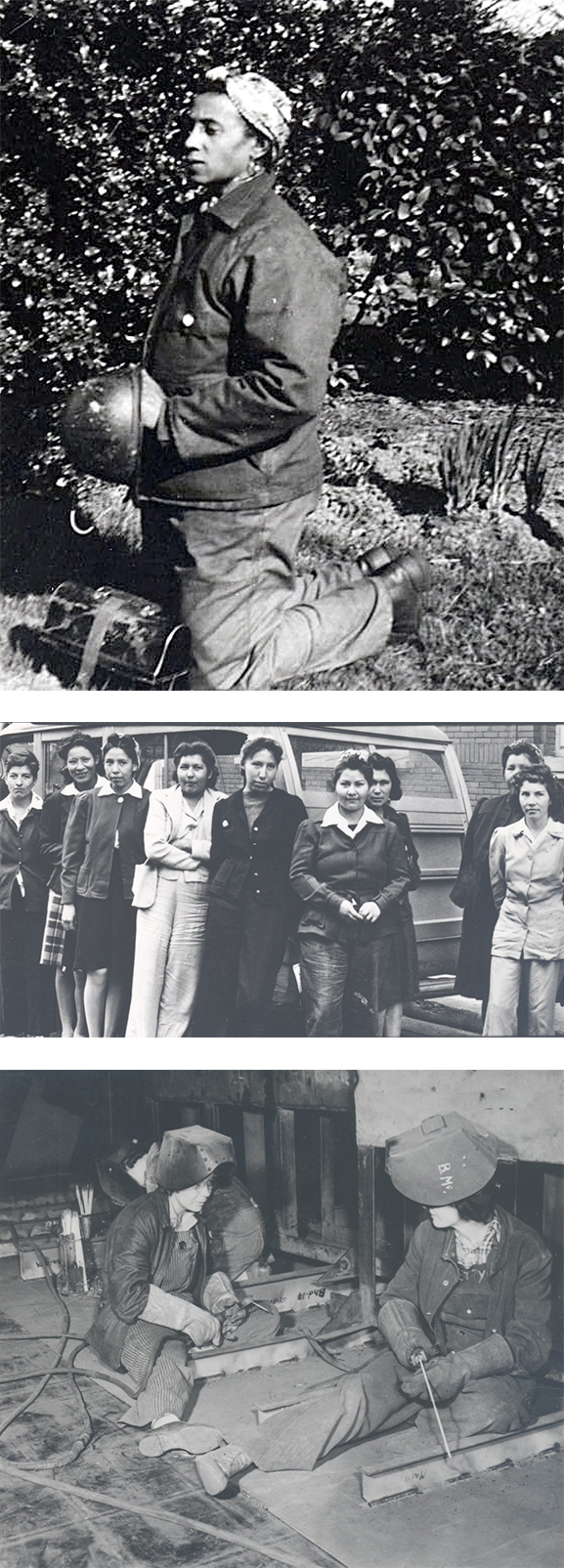

Native American women from Chemawa train to work in shipyardsAugust 1942 Oregon Journal collection, 013610 |

When the labor market opened up during World War II, more than 65,000 Native Americans worked for war industries or joined the armed forces. Historian Grace Gouveia estimates that one fifth of Native American women who were able to work took jobs off the reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) helped recruit those workers and facilitated their training and placement in shipyards and other industrial worksites. About 800 Indian women joined the armed services during the war, many recruited from off-reservation boarding schools. Read More |

||

| |

||||

|

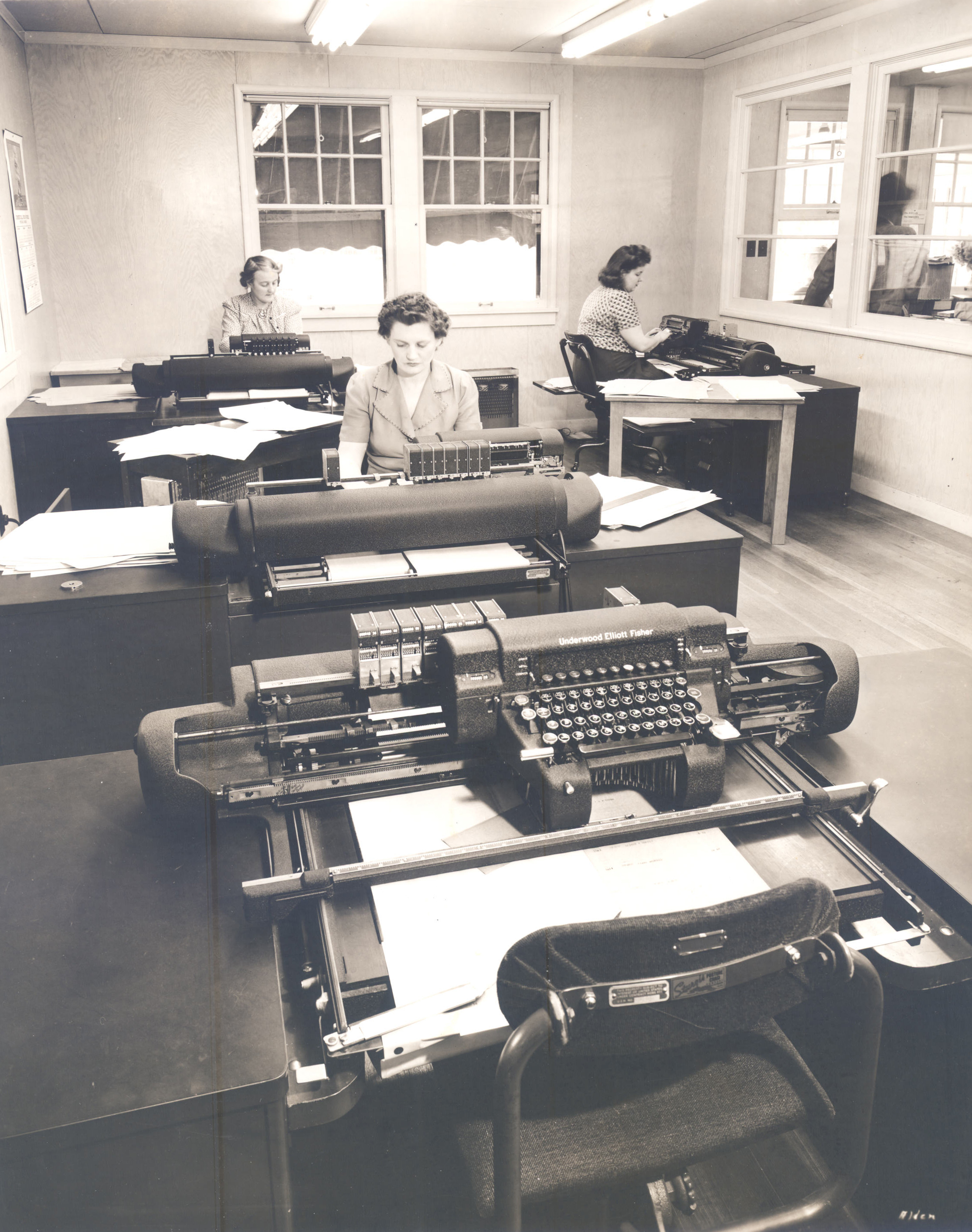

Albina Engine & Machine Works officec. 1943 Albina Engine & Machine Works collection, org lot 512

|

Oregon shipyards added hundreds, sometimes thousands, of new workers to their payrolls during World War II. Employers recruited women to fill positions typically held by men, mainly welding and pattern-making. But women also continued to work in jobs they dominated before the war, including clerical. The Albina Engine & Machine Works was formed in 1904, and was already repairing and building ships by the time the shipbuilding boom came to Portland in 1942. Albina expanded its workforce and production, and hired more women to work in its accounting and bookkeeping office. Read More |

||

| |

||||

|

"Grandma Crew" at the Oregon Shipbuilding Co.October 1944 Oregon Journal collection, 006451 |

The lucrative shipbuilding contracts given to Oregon shipyards during World War II created new job opportunities for women, who were recruited to fill jobs left open by men drafted into the armed services. The jobs were well-paid and interesting, which attracted women from all over the region. Although most women who worked for shipyards were already in the workforce in some campacity, many women who had either retired or had never worked showed up at the employment office. Read More.

|

||

| |

||||

|

Iona Murphy at Oregon Shipbuilding Corp., Portlandc. 1943 Ray Atkeson, OrHi96923 |

This ca. 1943 photograph, taken by Ray Atkeson, shows Iona Murphy welding in an assembly building at the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation in Portland. During World War II, up to 30,000 women worked in shipyards in Portland and Vancouver, Washington, building tankers, aircraft carriers, and merchant marine transportation ships for the war effort. The Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation was one of three shipyards owned locally by the Kaiser Corporation. Atkeson was a photographer who documented Oregon’s people and landscapes from 1928 until his death in 1990. Read More |

||

| |

||||

|

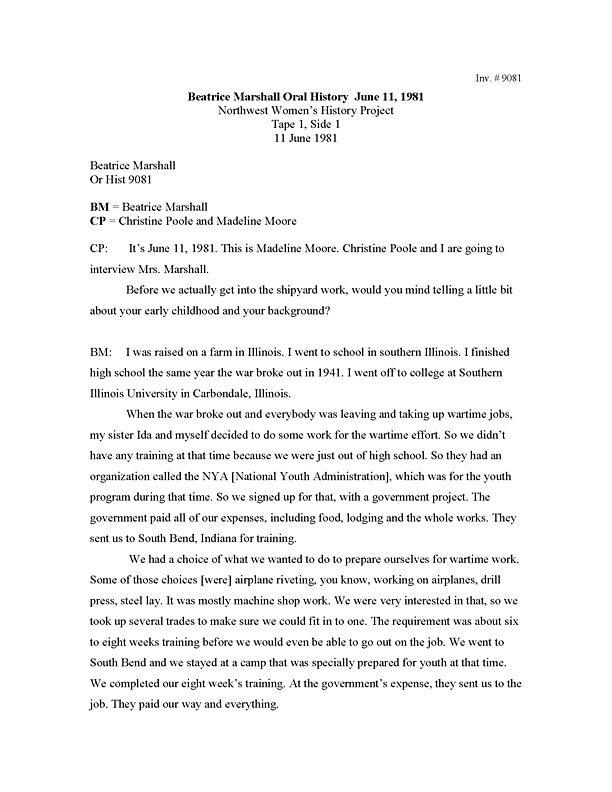

Beatrice Marshall's Oral HistoryJune 11, 1981 Christine Poole and Madeline Moore, OrHi9081 |

Beatrice Marshall was interviewed by Christine Poole and Madeline Moore as part of the Northwest Women’s History Project. In this transcribed excerpt of her interview, she recalls her experiences in Portland’s shipbuilding industry during World War II. An unabridged version of this transcript can be viewed at the Oregon Historical Society’s research library. After receiving specialized training for war-time industrial labor, Beatrice Marshall and her sister Ida moved to Portland to exploit their new skills in the city’s shipbuilding industry. Because the war had sapped the nation’s industrial workforce of a large portion of its male workers, industrialists like Henry J. Kaiser began to hire women in large numbers. Like many other women, Beatrice and Ida hoped to take advantage of the newfound employment opportunities. Unfortunately, the two sisters found that the color of their skin precluded them from most job prospects that were available to white women. Regardless of their specialized training, they were confined to jobs that required them to either push a broom, scrub floors, or scrape paint.

|

||

| |

||||

|

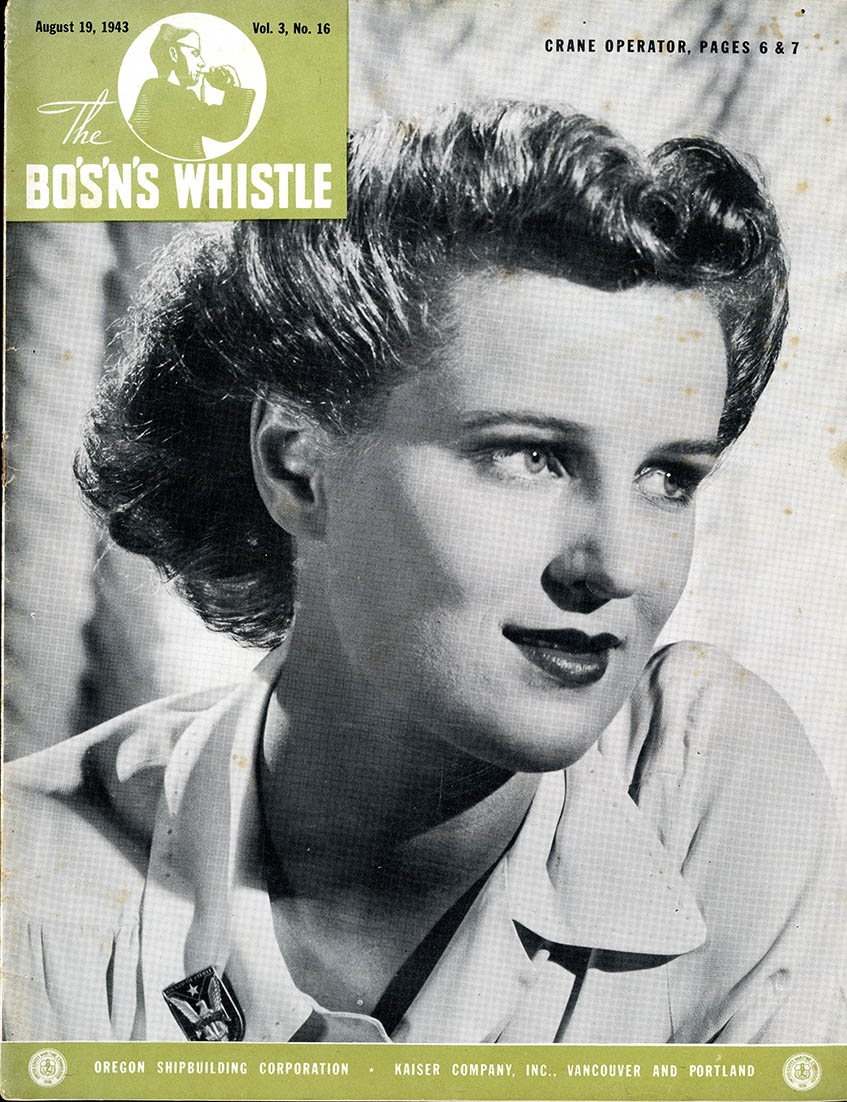

The Bo's'n's WhistleAugust 19, 1943 Hermina Strmiska Collection, acc#25441 |

The Bo’s’n’s Whistle was an in-house publication distributed to employees of the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation (OSC), owned by Henry Kaiser. The name comes from the bosun’s whistle, an instrument used by naval boatswains to alert crewmembers to ship commands. Kaiser built and operated three shipyards between 1941 and 1945—two in the Portland area and one in Vancouver, Washington— which employed tens of thousands of men and women. The presence of women was both welcome and troubling to the male employees. They needed the labor help, but they were also wary of women’s capabilities and temperaments on the job. As women stepped out of their traditional gender roles, they challenged stereotypes about feminine frailty and domestic responsibilities. This tension is illustrated throughout the magazine, beginning with the glamour shot on the cover of a young welder and continuing in cartoons about domestic chaos brought on by shipyard employment. Read more

|

||

| |

||||

|

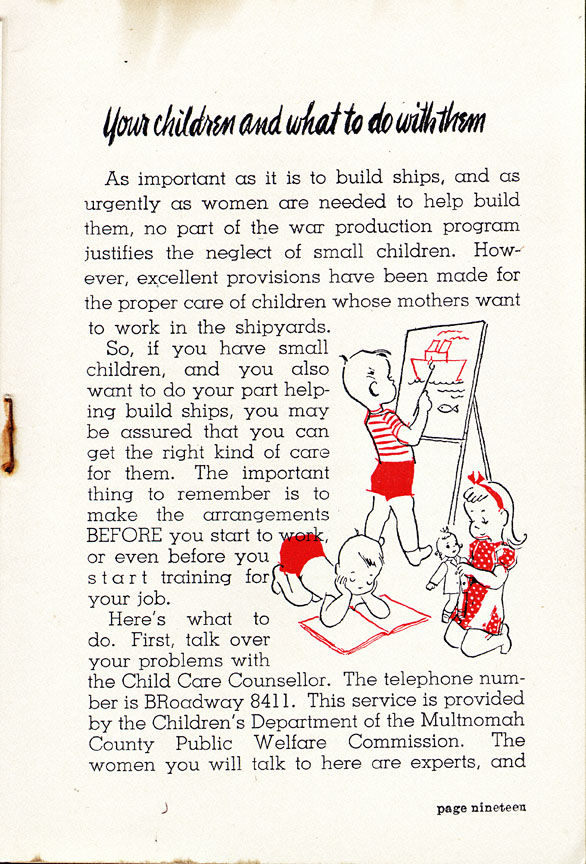

Handbook for New Women Shipyard WorkersAugust 1943 Portland Public Schools, Mss2547 |

In 1943 Portland Public Schools produced a handbook designed to orient new women workes to life in the shipyards. One section dealt with the problems of childcare. During World War II, women were actively recruited for employment in the nation’s defense industries. In Oregon that meant laboring in the shipyards. Such employment proved attractive, offering working women a considerable advance in wages and the opportunity to perform skilled labor previously the domain of men. In addition, many valued the work as a substantial contribution to the war effort. Increased reliance upon women to fill the labor void, however, posed a number of problems for both workers and employers. Concerns about child-care surfaced quickly. Questions arose regarding the effects the absence of working mothers might have on their families. Employers attempting to fill production quotas were faced with unexpected absenteeism from workers trying to balance the needs of home with those of the job. Read More

|