The Politics of Assimilation

By 1920, the drive by eastside small businessmen for increased political power became encased in a national fear of subversive foreign influence. In 1919, the first year after World War I, many labor unions struck for higher wages to compensate for inflation during the war. Many businessmen claimed that the strikes were inspired by subversives, and the attorney general of the United States, A. Mitchell Palmer, authorized the arrest and deportation of foreign residents suspected of membership in anarchist or Communist cells. To meet the alleged threat more benignly, a new veterans organization, the American Legion, in conjunction with settlement houses, public schools, and some social agencies, financed classes in English and American history to prepare immigrants for citizenship.

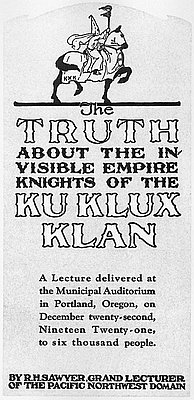

In Portland, as elsewhere, the fear of foreigners went beyond educational campaigns. Members of local fraternal orders proposed a law similar to those passed a few years before in California and Washington to prevent foreign residents who were not eligible to become citizens, namely the Japanese, from buying land. With organizers arriving in Oregon from California and the South, the Ku Klux Klan held meetings in east Portland denouncing the Catholic Church. Local Klan leaders argued that their own social characteristics as native-born white Protestants identified them as uniquely loyal to the country and, therefore, entitled to special economic opportunities. When an outraged Catholic delegation asked Mayor George Baker to prevent the Klan from using public buildings to defame loyal American Catholics, he claimed that the organization was too popular to suppress. In the spring 1922 primary elections, the Klan supported two candidates for the Multnomah County Commission and a slate of delegates to the state legislature. The commission candidates were both elected, and all but one legislative candidate survived the primary.

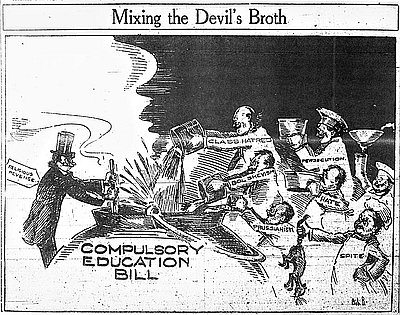

The Klan also seized on an initiative proposed by the Scottish Rite Masons that would require attendance of all children at public schools. Klansmen argued that private schools undermined democracy by isolating a privileged elite and by promoting the religious distinctions that prevented the public from reaching a moral consensus. In the November election, the compulsory public school initiative passed, with two-thirds of its statewide victory margin in east Portland. Klan spokesmen also insisted that candidates endorse the view that foreign residents ineligible to become naturalized citizens should also be ineligible to own land. The 1923 session of the legislature, led by Portland Klan members, passed such a law.

Most of the success the Klan enjoyed in 1922 was reversed by 1925. The alien land law, which prohibited first-generation immigrants from owning or leasing land, was declared constitutional; worse, Japanese immigrants were denied access to citizenship by the U.S. Supreme Court. But in March 1924, the U.S. District Court declared the compulsory public school attendance law unconstitutional, a decision supported by the Supreme Court in 1925. At the same time, the Klan’s successful candidates for county commissioners were revealed to be dishonest and were recalled in 1924. With its most dramatic initiative success overturned by the federal courts, its leadership discredited, and racked by dissension over the endorsement of rival candidates for federal and Klan offices, the group lost membership and visibility.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

The Truth About the Ku Klux Klan, 1921

This pamphlet, whose title page is shown here, contained an edited version of “The Truth about the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” a pro-Klan lecture …

George Luis Baker (1868-1941)

George Luis Baker served on the Portland City Council and as Commissioner of Public Affairs before being elected mayor of Portland in 1917. He served until 1933, his …

Mixing the Devil's Broth, editorial cartoon

This political cartoon appeared on the front page of the Portland Telegram days before Oregon voters passed the initiative on compulsory public school attendance in the 1922 general …