Religion, Social Clubs, and Education

Merchants, craftsmen, and other members of the middle class described churches as the center of social life. By the late 1850s, mainstream Protestant denominations—Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists, Episcopalians, and Presbyterians—as well as Catholics and German Jews had organized congregations and constructed churches along Third, Fourth, and Fifth Streets. By 1880, the city directory listed fourteen Protestant churches in Portland and two more across the Willamette River.

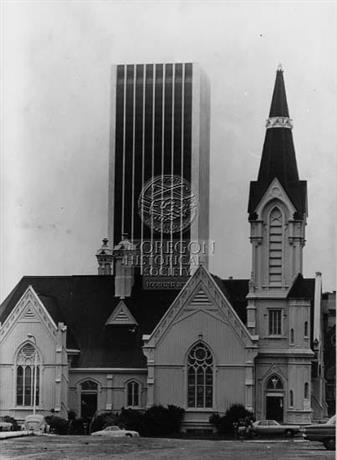

The Catholic Cathedral, two Jewish synagogues, an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and a Chinese Joss House identified ethnic population centers near downtown. Virtually all provided a cultural anchor by remaining at their locations for at least ten years. By the early 1890s, the pressure of higher real estate values and the lure of suburban neighborhoods led most congregations to erect new buildings in residential suburbs. Structures like the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, the First Congregational Church, the First Baptist Church, and Trinity Episcopal Church remained in place.

By the 1860s, men had established lodges of Masons, Elks, Good Templars, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, the Improved Order of Redmen, and the Knights of Pythias. These groups offered insurance benefits as well as a sense of brotherhood. By joining several lodges, men could find companionship for several nights each month. German Jews joined some of the Masonic lodges, but in the 1860s they reinforced the social boundaries of their community by starting their own B’nai B’rith lodges for health and death benefit insurance and for sociability. The Irish, Germans, German Catholics, Scandinavians, and even the British started benevolent societies, which provided direct benefits to members and information about employment.

In 1867, many of the city’s wealthiest Protestant merchants founded their version of an English gentleman’s refuge, the Arlington Club. There they could meet for lunch, discuss business, and formulate the position of the merchant elite on city issues. They built a permanent home for the club on Salmon Street at the head of the Park Blocks. Membership was by invitation and considered an entree to elite status. The German Jewish merchant elite, excluded from the Arlington Club, formed an equivalent in the Concordia Club in the 1880s, which was known for evening soirees and charitable activities. By the 1890s, it had built a clubhouse at Second and Morrison Streets. As the city approached a population of 90,000 people in the 1890s and the social classes were becoming more easily demarked, the social elite, like its counterparts in cities like San Francisco and Chicago, issued a social directory to celebrate its status.

Formal schooling began sporadically in Portland in 1847, with ministers and young men and women teaching classes for fees through the late 1850s. Even though the majority of Portlanders were without families and resisted being taxed, civic leaders like Josiah Failing and Rev. Horace Lyman persuaded voters to initiate a public elementary school. Common schools, they believed, would impart literacy and a uniform cultural heritage, which seemed especially necessary on a remote frontier with an unstable population. Multnomah County created a common school fund and began to hire teachers. With salaries low and classrooms packed, however, young men and women taught for only periods of time until they found more lucrative work.

By 1865, a permanent public school was built on dedicated property on Sixth Street, between Morrison and Yamhill. From the beginning, the practice was to have large classes taught primarily by unmarried women. Private education was supported by churches, with instruction again provided by women. The Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary opened St. Mary’s Academy for boarding and day students, while the Episcopal Church founded the Portland Academy and Female Seminary. By the mid 1870s, two additional public schools and a small high school had opened. The public schools increased staff in proportion to the growth of enrollment; but some students from wealthy families attended private schools, including an Independent German Day School, with Henry Weinhard as its president, and St. Helens Hall, a school for young ladies supported by the Episcopal Church.

Until 1867, the city denied African American students access to an education. That year, a school board resolution resulted in the opening of the Colored School, which operated until 1872, when Portland residents voted to admit African American children to public schools.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

From Horace Lyman to the Editor

Reverend Horace Lyman was a County School Commissioner in Portland and a strong advocate for public education. In this letter to the editor of the Oregonian, he responded …

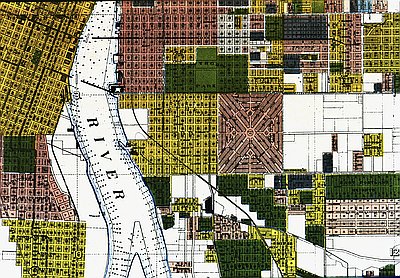

Park Blocks, 1878

The Park Blocks were set aside by early landowner Daniel Lownsdale in an 1849 survey. The narrow strip of blocks running north and south were substantially west of …