Portland as a Marketing Center

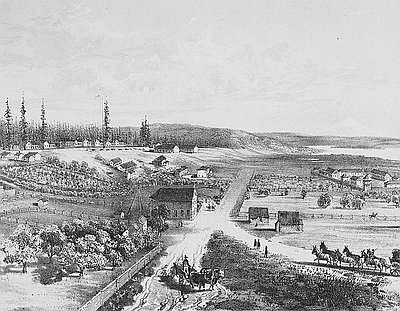

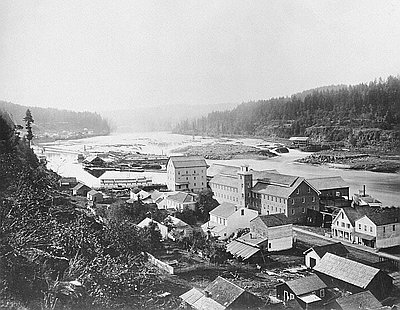

The West Coast developed rapidly in the late nineteenth century through capital and supplies funneled through its port cities. In the 1840s, the Pacific Northwest had two points for overseas trade: Fort Vancouver on the north bank of the Columbia River, the fur-trading center for Hudson’s Bay Company since the 1820s, and Oregon City, where the Willamette River went over a steep falls. But Vancouver was too remote from the new farms of the Willamette Valley, and Oregon City lacked secure moorings for ocean-going ships. After 1850, supplies and credit entered the region and farm surpluses left through Portland, on the west bank of the Willamette River, twelve miles below its confluence with the Columbia. There, ocean-going vessels could find a riverbank adjacent to safe moorings and a wide stream for turning around.

Portland emerged from the land swaps of local speculators to become a marketing center. In 1843, Boston attorney Asa Lovejoy and William Overton laid claim to 640 acres (one square mile) to found a townsite. Overton soon sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove, a merchant in Oregon City, and moved to the Southwest. According to Lovejoy, Pettygrove won a coin flip and named the site Portland after the largest city in his native state of Maine. Had Lovejoy won, the town would have been called Boston.

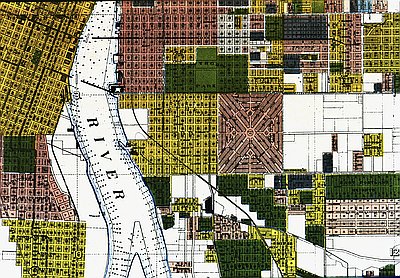

For their townsite, near what is now First and Washington Streets, the men had a surveyor lay out a simple grid pattern parallel to the riverfront, with sixteen 200-foot-square blocks subdivided into eight lots each. The streets running north and south were to be 80 feet wide, while the streets running east to west were to be 60 feet wide.

In 1850, Portland was home to 800 people. Population increased as farmers began selling local surpluses and importing manufactured goods. To induce more farmers to settle and form families, Congress responded to a request from the first territorial legislature and in 1850 passed the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act, which awarded 320 acres to each single man. Women who were married by December 31, 1851, would also receive a 320 acres. The Willamette Valley, the richest farmland between the Missouri River and the Pacific Ocean, began to fill with Middle West farm families eager to raise cash crops.

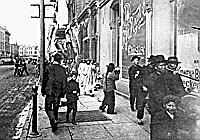

By the spring of 1851 young merchants from Massachusetts and New York had arrived with a stable source of supply and surer ideas about developing a city. William S. Ladd, Josiah Failing, Henry W. Corbett, and Cicero Lewis all had allotments from New York supply houses for which they had previously worked, and each set up a store on Front Street. By the mid 1850s, the New Englanders were joined by several young Jewish merchants, including Bernard Goldsmith, Philip Wasserman, Louis Fleischner, and Louis Blumauer, who had recently emigrated from various German states. They also had supply agents in San Francisco and New York and younger brothers willing to operate small general stores in rural areas. By 1870, the city had grown tenfold in population, largely through its commerce.

San Francisco grew wealthy at first as the exporter of gold and later of silver from Nevada’s Comstock Lode, but in the long run as the supplier of manufactured goods to regional marketing centers. Between 1850 and 1880, Portland’s merchants grew wealthy on a smaller scale by balancing four interrelated activities, at least three of which depended directly on ties to San Francisco.

First, they were wholesale distributors throughout the Northwest for imported manufactured goods. Second, they became marketing agents by extending credit to farmers and purchasing the harvested produce for resale to San Francisco. The most successful—Ladd, Corbett, and Failing—turned their wholesale businesses into banks, which became the mainstay of the city’s economy. Third, merchants speculated in land within and beyond the city limits. As Portland’s population expanded and the city annexed subdivisions, merchants like Ladd and Corbett sold land at great profit to real estate developers. Finally, they invested in local industries, including wool manufacturing at Oregon City, flour mills in Albina, and stone cutting and paving in Portland, for which men like William Ladd received lucrative city contracts. Their most successful venture was the organization of the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (OSNC) in 1860, with Capt. John C. Ainsworth and Robert R. Thompson of The Dalles, who had made money in sheep and cattle ranching.

The OSNC was the city’s largest early corporation. It built wharves and warehouses, had dozens of employees, and annually moved tens of thousands of people who spent money at Portland’s hotels, restaurants, and entertainment venues. The OSNC monopolized shipping and passenger traffic on the Columbia River, at least until the arrival of a railroad in 1883. Farmers and ranchers in eastern Oregon hated it because it charged such high freight rates.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Oregon City and Willamette Falls

This 1867 photograph, taken by Carleton Eugene Watkins, shows Oregon City and the Willamette Falls soon after the first portage railroad was built there. Oregon City had been incorporated …

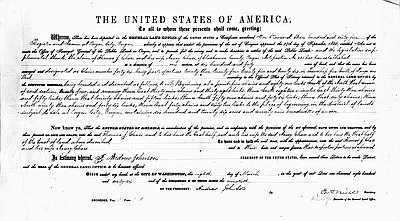

Oregon Land Donation Claim Notification

This image shows a certificate issued March 8, 1866, that grants 640 acres of land in Clackamas County to Thomas J. Chase and his wife, Nancy. The document …

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad …