Renewing the Public Space and the New Urbanism

Within a downtown whose property owners were receptive to the New Urbanism, public space was reconfigured to appeal to pedestrians. Even the eruption of Mount St. Helens in May 1980, which led hotel managers and bankers to fear a slowdown in tourism and construction, had no effect on redevelopment. By the mid 1980s carefully spaced office towers transformed the downtown. Across from the new Waterfront Park, the Public Market, a landmark of the Depression era, was replaced by Portland General Electric’s Willamette Center. Two blocks to the west a series of parks that included a dramatic walk-through fountain named for Ira Keller, former chairman of the Portland Development Commission, were completed.

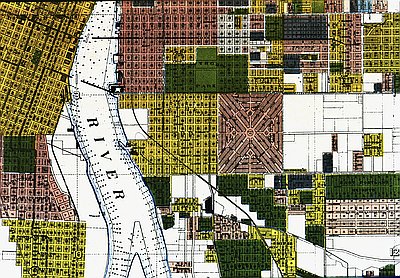

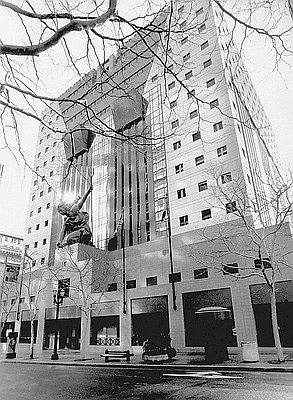

The Pioneer Courthouse was restored and Pioneer Courthouse Square, intended to be the center of downtown, was built on the former site of a parking structure. Visitors writing in national magazines were duly impressed by the landscaping and the retail shopping that reduced the large downtown buildings to human scale. Complementing the focus on the larger urban plan has been coverage in The Architectural Record of impressive new buildings. The most elaborate articles were devoted to Michael Graves’ startling Portland Building, with others covering the nearby Justice Center, Willamette Center, Pioneer Courthouse Square, and townhouse developments in different parts of the city. The new structures, combined with the old, have finally given life to the Olmstead and Bennett plans of an administrative center and entertainment district at the core of downtown.

Urban renewal and land use planning changed the face of the city. A grassroots political movement to contain urban renewal was inspired most by Governor Tom McCall’s effort to restore the environment through the control of growth. His call for land use planning recast the city from a site for public construction to an active agent managing regional growth. The spirit to contain growth took political form when neighborhood activists took to the streets. On August 19, 1969, for example, a group called Riverfront for People consisting of 250 adults and 100 children held a picnic on a barren strip between the west bank of the Willamette and Harbor Drive. When this protest was augmented by City Club of Portland lobbying, the city tore out Harbor Drive and created Riverfront Park, subsequently named for Governor McCall.

The neighborhood groups then found in Neil Goldschmidt, a new city commissioner in his early thirties, a spokesman for rejuvenating environmental assets. With his election as mayor in 1973, the city created an Office of Neighborhood Associations to bring local communities into the formal land-use review process. For the first time since the adoption of the commission form of government in 1913, geographic districts could find a legitimate channel to officers of government. By 1975, an alliance of neighborhood groups and downtown business interests defeated plans for a new freeway through east Portland that would connect the downtown with Interstate 205. Women in particular emerged from neighborhood groups to provide leadership. By the early 1990s, Governor Barbara Roberts, Beverly Stein, a Multnomah County commissioner, and Vera Katz, Portland’s mayor, collaborated for administrative efficiency. As historian Carl Abbott noted, Portland had become the capital of a small revolution in political culture.

As the spokesman for a political movement, Goldschmidt hoped to reverse the pollution of Portland’s air and water by curtailing sprawl and the use of automobiles on which it depended. He believed that a public transportation strategy would mesh with Governor McCall’s struggle to protect Willamette Valley farmland from suburban subdivisions and to make accessible the riverfronts and ocean beaches. Goldschmidt’s supporters found allies in downtown businessmen hoping to rejuvenate the central business district, with its unique amenities—an art museum, theaters, a concert center, and a state university. They believed that a high-speed public transportation corridor, in conjunction with parking limitations, height and bulk limits for buildings, and an increase in housing density requirements for both downtown and residential neighborhoods, would draw people back.

The coalition of urban planners, central city developers, neighborhood activists, and environmentalists made land-use planning a state-wide priority. For the Portland region they created a Metropolitan Commission with an elected executive and seven regionally elected councilors. In 1978, with new enforcement provisions obtained from the state, Metro focused on regional waste disposal and on running the Portland Zoo and various parks. More importantly, it also developed—after many public hearings with testimony from neighborhood groups—land-use planning regulations as required by the state’s new Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC). By 1992, it implemented more comprehensive planning and suburban zoning requirements that extended over three counties and their twenty-four cities.

This cluster of proposals intended to alleviate both the pollution and sprawl that derive from reliance on the automobile has come to be called “The New Urbanism.” To pursue its goals, Goldschmidt diverted federal funds from a freeway project opposed by eastside neighborhood groups to build the downtown transit mall and a high-speed light rail line, the Metropolitan Area Express (MAX). The first MAX line, completed in the early 1980s, connected the business corridor to Gresham in the east; the second line, completed in 2002, connected the traffic mall to Beaverton. By 1990, the federal census reported that over 11 percent of Portland’s work force used public transportation, while about half that proportion did in Gresham.

From the beginning, opposition arose to the new transportation system and the imposition of high-density housing goals. Electronics firms, the majority located in Beaverton, hoped for a post-industrial regional economy located in that suburb and opposed strongly light rail proposals. Ignoring Goldschmidt’s vision of regional integration, they believed their employees lived and worked in the suburbs, and they opposed compulsory pay roll taxes to support an expensive system they would never use. They joined a taxpayer revolt that had originated in Washington and Clackamas counties, where neighbors enjoyed their large lots and resented efforts to intensify land use. By 1991, they were responsible for passing state-wide property tax limitations.

© William Toll, 2003. Revised and updated by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

The Portland Building

When the Portland Building on Southwest Fifth and Main opened in 1982, the design by architect Michael Graves then a “relative unknown in the world of architecture” opened to …

Tom McCall (1913-1983)

This photograph shows Governor McCall visiting an Oregon beach on May 13, 1967, in the midst of a period of contentious, state-wide land-use rights debates. At a Junior …