Themes for an Urban History

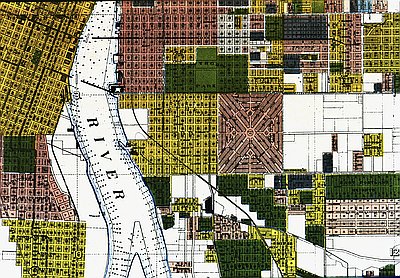

Cities are created through charters, and state legislatures designate names, geographic boundaries, governmental form and election procedures, and powers to make contracts and tax. But students of a city’s history usually start their inquiries elsewhere. Those who admire landscapes or architecture may focus on how a city’s natural setting has been reshaped. Planners hoping to solve contemporary problems may trace how the platting of streets and zoning laws have affected traffic congestion or public health. Political leaders may examine how struggles to change election laws restored power to individual citizens.

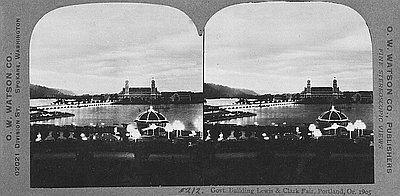

Portland is probably best understood as a river port like St. Louis or Cincinnati, with access to a vast agricultural hinterland. The city has also been carved out of a beautiful rain forest, whose terrain and lush foliage have dominated its image. Visitors to the Lewis and Clark Exposition in 1905, such as Walter Hines Page, were impressed by the towering trees and the dramatic vistas from Portland’s West Hills, which afforded a view of Mt. Hood to the east and Mt. St. Helens to the north. He also rhapsodized about “the flour mills, the lumber mills, the trade, coastwise and across seas, the great jobbing houses, the very good hotels, the strong banks.”

To set Portland’s development within the context of the American city system, however, it is useful to look at what the city did not have. Unlike St. Louis or Chicago, Portland through World War II did not have a sufficiently large regional market to develop heavy industry. The city never attracted a large industrial working class of East European immigrants, and only during World War II did large numbers of Southern whites and African Americans appear. Unlike Detroit or Chicago, Portland’s sense of class antagonism was not highlighted by many ethnic and racial divisions. Nor did Portland have a political machine that dispensed jobs to immigrants in exchange for votes.

While Portland developed a reputation for being a place where bankers, developers, and their legal advisers controlled politics, the city’s elite nevertheless faced occasional rebellion. During the Progressive Era, spokesmen for small businessmen and skilled workers illustrated how interest groups could create instruments of government through which they could directly affect legislation. Innovations in government, including the referendum, initiative, and recall, became known nationally as the Oregon System. But because Portland remained a midsized commercial city rather than an industrial metropolis, its merchants and bankers continued to shape its physical growth through the 1960s. In the 1970s, a new middle-class rebellion was triggered by neighborhood discontent with urban renewal. The resulting experiment with a new form of government, the Tri-County Metropolitan government, gained voters’ support in 1978 because legal boundaries still did not coincide with racial and class divisions.

Portland history also needs to be understood in the context of regional history. As the city developed sprawling suburbs to the east and a larger regional market, it seemed to be more independent. The infusion of federal investment at Bonneville Dam and the awarding of military contracts during World War II furthered the illusion of economic autonomy. After the war, local political leaders seemed indifferent to industrial and educational innovations in other West Coast cities, and Portland’s retooling lagged.

Since the 1970s, Portland has tried to coordinate a civic and architectural renaissance with the expansion of high-technology firms in the suburbs. These contending developments attest to the city’s transition from a river port to an urban node on the Pacific Rim. Tightened controls over the landscape, however, could not be matched by control over the economy. New sources of employment and new suburban land uses illustrate the continuing illusion of local autonomy. A history of the city reveals how the new polarities of regional cohesiveness and global interdependence have superseded the civic indifference and social insularity that prevailed at the mid twentieth century.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Night View of the Lewis and Clark Fair

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition and Oriental Fair in Portland was illuminated at night by 100,000 lamps that outlined the graceful fair buildings, streets, and walkways. “No …

William S. U'Ren (1859-1949)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Oregon was known for its experiments with democratic reform. The state developed a system of government that came to be known …