One of the most important characteristics of the Native fishery is the effects of ongoing negotiations between Indian and non-Indian fishers regarding the treaty right to harvest. Unlike non-Native fishers, many Native people in the Pacific Northwest reserved a right to a subsistence and commercial fishery through treaties negotiated with the federal government in the 1850s. Under the provisions of these treaties, Indian bands and tribes ceded millions of acres of land to the federal government. They also reserved small territories for their own use (reservations) and kept specific rights to resources on and off their reservations. When Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens (1853-1857) began to negotiate treaties with tribes in western Washington, he included the following provision in the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek:

The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing, together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on open and unclaimed lands.

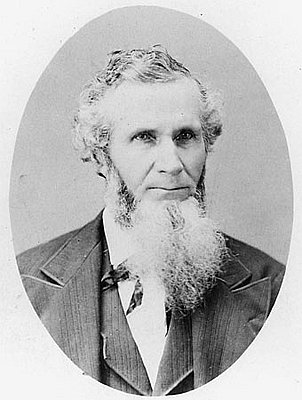

Stevens believed that Indian leaders would not sign treaties in which their people had to relinquish most of their land unless the U.S. government recognized Indian fishing rights both on and off the reservation. Joel Palmer, the Indian agent in Oregon Territory (1853-1857), included similar language in many of the treaties he negotiated.

The reservation of small parcels of land for the tribes and the right to harvest food items off the reservations are two of the most significant elements of the treaties of the 1850s. They have lasting importance, because they provide many tribes with homeland territories and rights to the resources of the region.

Not long after reserving their resource rights through treaties, Columbia River tribes were forced to defend their rights through the court system. The treaty language that recognized resource rights was vague. What did it mean, for example, to have rights “in common with the citizens of the territory”? The courts interpreted the provisions of the treaties and determined how they would be enacted.

The first regional fishing case was heard in federal court in 1887, when the U.S. government sued a private property owner on behalf of the Yakama Nation (U.S. v. Taylor). Frank Taylor had fenced his land in Klickitat County, Washington, preventing Indians from crossing it to reach traditional fishing sites. Subsequent cases protected Indians who had adopted modern fishing equipment, affirmed Indian rights to participate in the commercial fishery, and limited the state’s jurisdiction over Native fishers. By the mid-twentieth century, federal courts had upheld and defined treaty-fishing rights in numerous cases.

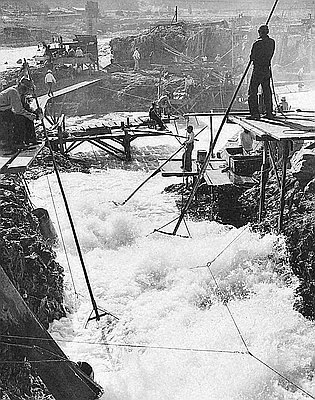

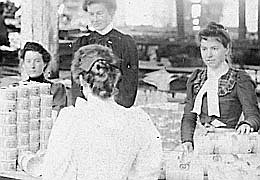

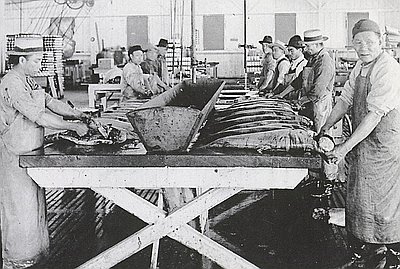

The two biggest threats to Indian fishing rights were (1) private property owners who sought to keep Indians from crossing their lands and (2) regulatory agencies that sought to bring Indian fishers under their jurisdictions and often adopted race-based regulations that targeted treaty fishers. Industry also threatened the Native fishery. While a non-Native commercial fishery competed directly with Indian fishers, timber companies and river development also negatively impacted Indian fishers. As the twentieth century progressed, Indian fishers had access to fewer sites, the runs were diminished, and there was significant competition from sports and commercial fishers.

By mid-century, fishing rights had become the most important issue for many individuals and the tribal governments that represented them. The post-war period saw a rise in activism among Indian fishers to call attention to diminished fishing rights and to demand that state and federal governments recognize their treaty rights. Indians held fish-ins, went to court, and began a public relations campaign to force the issue into the national arena. Successful efforts in Puget Sound were reflected on the Columbia River; and in 1974, Indians in the region won important concessions, including up to 50 percent of the harvestable catch (U.S. v. State of Washington).

Post-war activism reflected a rise in civil rights activism around the country. Indians in the Pacific Northwest adopted some of the strategies of the African American civil rights movement, though Indian activists rooted their demands in treaties rather than the Bill of Rights. Their activism, then, was part of a larger series of national movements toward equality for the nation's minority citizens. It was also a response to the river development that began in earnest in the 1930s and continued through the 1970s.

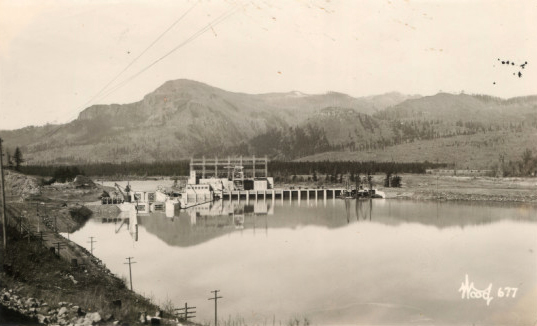

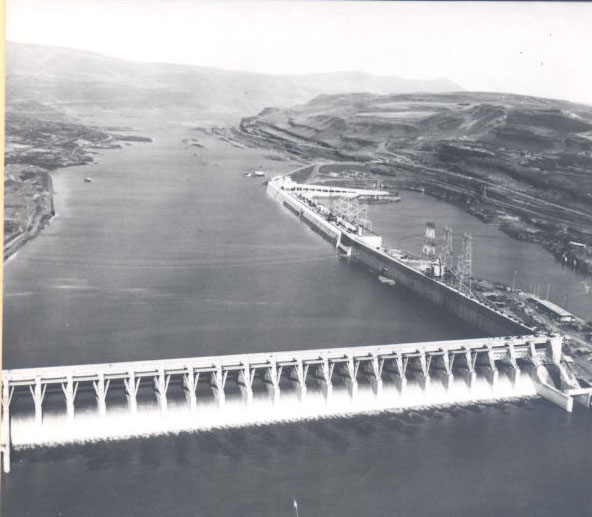

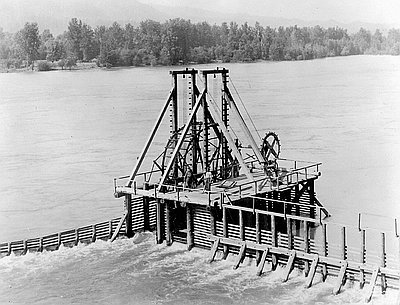

Dams on the main stem of the Columbia and on many of the river's tributaries destroyed traditional fishing sites under slack-water reservoirs. Bonneville Dam (1938) inundated the Cascade Rapids, Grand Coulee Dam (1941) inundated Kettle Falls, McNary Dam (1953) inundated Umatilla Rapids, and The Dalles Dam (1957) inundated Celilo Falls and the Long Narrows. In addition to affecting where Indians could fish, the dams negatively impacted the runs, raising a question about whether they could survive in the Columbia River Basin.

© Katrine Barber, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.