Gendering American Indian Fisheries

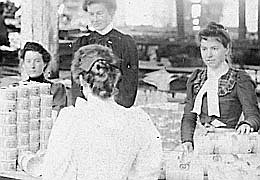

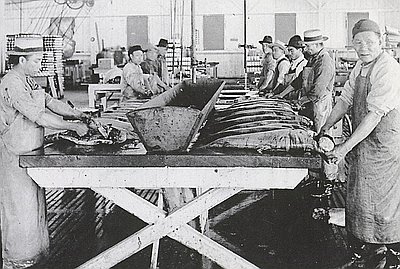

While different bands of people in the area took salmon using many different technologies, generally men did the harvesting and women the preparation of salmon for consumption and trade. This division of labor was not absolute. Men could prepare salmon and women could harvest, and Indians did not use the division to elevate men over women or vice versa. Both aspects of the labor and its cultural meanings were vital to each other and to the survival of the families, bands, and tribes in very material and spiritual ways.

As part of their work along the mid-Columbia, women regularly packed ninety-pound baskets of dried salmon for trade. In the many hours devoted to this activity, women often told stories associated with their tasks, such as the story of an ogress who seduced Coyote. Coyote saved himself only by destroying the ogress’s fanged genitals with a large, wooden, phallic-shaped salmon-packing pestle—the very same as those used by women to pack the trade baskets. Men and women knew the story, but did not tell it to each other in polite company. For the women, the story surely evoked chuckles regarding the foolishness of men. Among the men, it was potentially a reminder of women’s power. Such pestles were a constant reminder to everyone of the deeply gendered cultural meanings of what might seem to outsiders to be a mere subsistence activity. Food harvest and preparation evoked a host of gendered meanings, for all activities were imbued with culture.

The arrival of non-Indians to the region did not bring immediate changes for Indian people in their relationship to the fisheries. In comparison to other commercial salmon fishing and canning regions, Native participation in Oregon’s commercial fisheries was relatively limited. Yet, families did sell salmon to canneries and tourists. Students would need a more extensive set of documents than those provided here to evaluate potential shifts in gender roles for Indian men and women caused by engaging a capitalist market.

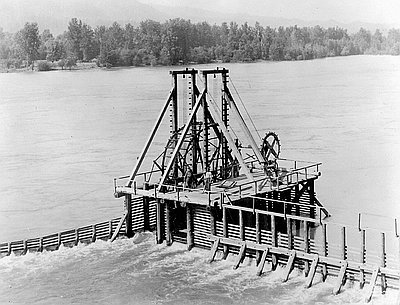

We would also be well served to ask how the struggles for broader Native rights, especially the legal and treaty battles surrounding the defense of fisheries, have been couched in language about how men from various tribes will gain access to the fisheries. Even when highways cut through salmon processing grounds or when non-Indian reformers called for better hygiene at fish-processing camps, the focus was primarily on the harvesting site. As a consequence, as Elizabeth Vibert suggests, analyses of women have been submerged and obscured. Likewise, some historical documents, such as photographs showing men dipping along the river, provide at least a partial window into aspects of men’s culture, but not that of women. Much remains to be done.

© Chris Friday, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

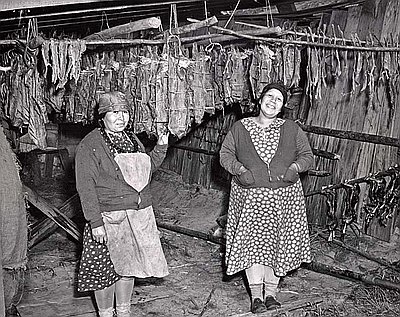

Women Dry Salmon at Celilo Village

This photograph shows Warm Springs tribal members Edna David (left) and Stella McKinley (right) drying salmon at Celilo Village. It was taken by an Oregon State Highway Travel …

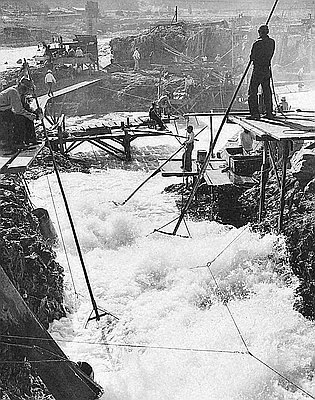

Indians Fish at Celilo Falls

Celilo Falls was an important center for native trade, culture, and ceremony. For at least 11,000 years, tribes throughout the region, and from as far away as the …