Gender and Landscape

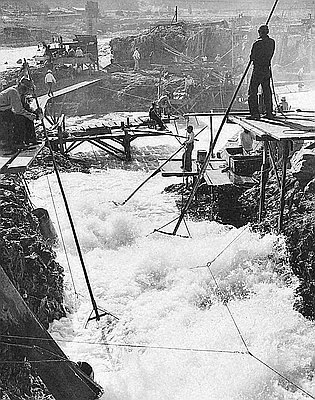

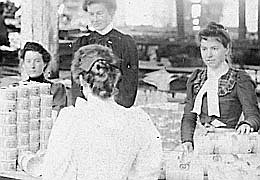

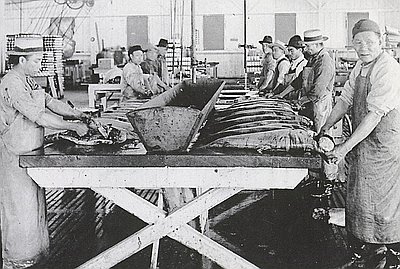

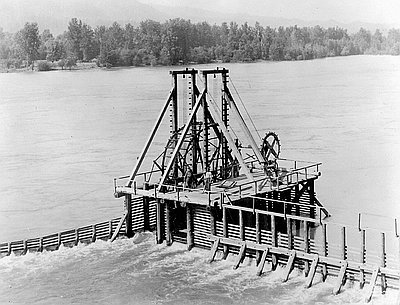

Documenting the location of fish traps, gillnet grounds, fishwheels, canneries, dams, hatcheries, and environmental abasement is important, but to do so without taking a look at gender leaves significant holes. Compare the photo of the exterior of the Eagle Cliff Cannery, with the interior photos showing Chinese and women cannery workers. Understanding the story here is important. A brief inspection of the exterior photo of the Union Fisherman’s Cooperative Packing Company in Astoria, especially the nets, is helpful. Many white fishermen made their own nets and took considerable pride in that activity, believing that each net was reflective of the fishing locale and their own skills as a fisherman. As Irene Martin explains, among white male gillnetters “nets are individual creations” and measures of an “individual’s skill.” Being known as a “good net man” was a badge of honor that took into account making and using the appropriate net for the right location and in the most successful fashion. Ironically, early in the twentieth century, canning companies sometimes hired Chinese workers to knit company nets but kept the activity secret from the fishermen out of fear of their potential reaction. For many Chinese men, net knitting was one more avenue to generating enough cash to send money to their families in China.

Net knitting was not just men’s work. Among Finns, women held net-knitting work parties known as talkoot. Georgia Maki recalled: “There’s a rhythm. You work up a rhythm.” People “knew I was knitting because the windows were singing.” Jack Marinocovich remembered his grandmother’s net-knitting as “an art.” For these women, the social aspects of knitting, contributing to the family’s welfare, and having pride in individual skills and speed were components of what it meant to be a good woman.

Accepting an ungendered vision of the plant exterior allows viewers too easily to let these critical webs of association slip past. Gender is not the only category of analysis, but considering it provides a starting point for understanding the many deep cultural and historical meanings of salmon fisheries.

© Chris Friday, 2006. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014