Claiming the Land

As desirable Willamette Valley farmland grew scarce, settlers turned to southwestern Oregon. The Donation Land Claim Act, passed by Congress in September 1850, enabled citizens to acquire free, farmable land. A married couple could now claim 640 acres of land and a single man 320 acres, provided he or she was in Oregon Territory by December 1, 1850; claims amounting to half that much were available after that date. In 1853, taking advantage of the original act and subsequent amendments, emigrants poured into the Bear Creek, Rogue, and Illinois valleys. “This day,” wrote Iowan Nathaniel Myer in 1853, “mother and my two youngest daughters and myself moved our bed into the cabin built by my sons for us with intention to sleep under a roof which none of us had done since the 23rd of March last.”

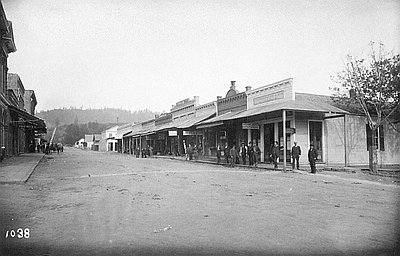

With settlement, the land changed forever. White farmers turned Native village sites and camas fields into pastures and converted native grasses to wheat and oats. Within months, Di’tani became Table Rock, Me-tus became Humbug Mountain, and Dilomi became Jacksonville. The Euro-Americans gave new names to the creeks and mountains, calling them Wagner Creek, Sexton Mountain, and Hunter Creek.

By late 1853, log houses stretched along roads through the Bear Creek Valley, along the Rogue River, west to the Upper Illinois River, and into the small interior valleys near the coast. With a fierce desire to recreate their former homes and familiar landscapes, the settlers transformed what they perceived to be a wilderness. In 1854 and 1855, when U.S. government deputy surveyors ran township and donation land claim boundaries in the region, southwestern Oregon land could, for the first time, be owned and sold.

While Indians had adapted to nature, the new inhabitants subdued it. Their livestock polluted the streams, broke down the banks, and destroyed native grasses such as Idaho fescue and bluestem. Farmers burned brush to clear fields for grazing stock, and hunters unleashed fires and rarely bothered to extinguish them. “It seems as though no year shall pass but what the woods are set afire and the country deluged with smoke,” observed the editor of Jacksonville’s Democratic Times in September 1874.

California was an important source of supplies for southern Oregon communities. Packers used the Oregon-California Trail—used for years by Indians and fur traders—to ship goods over the Siskiyou Mountains from Sacramento and San Francisco. Another important pack trail led into the Rogue River Valley from Scottsburg on the Umpqua River, where ships from San Francisco could safely stop. With Portland and Oregon City themselves dependent on California for goods in the early years, the region’s residents looked southward for necessities rather than to the region’s own population centers.

Ferries at strategic locations on the Rogue shuttled travelers across the river. The Mountain House at the base of the Siskiyou Mountains, south of present-day Ashland, offered lodging. Travelers also found accommodations at Evans’ Ferry on the Rogue, at the Grave Creek House north of Grants Pass, and at the Six-Bit House at present-day Wolf Creek.

In 1860, the California Stage Company began regular trips over the California-Oregon Trail between Portland and Sacramento. Pushing hard to cover 710 miles in six days, the large, swaying coaches, pulled by four- or six-horse teams, carried passengers and freight over steep mountains and through dust-choked valleys. “The journey from Sacramento to Portland,” one traveler complained, “seems interminable, and there are rumors of passengers who died of old age upon the road.”

While farmers won livelihoods from the land through agriculture, others turned to logging and mining. To supply materials for valley residents and the railroad, small logging operators skinned the timber from the hills and built sawmills on any stream with enough water to power their saws.

In the foothills and interior valleys, loggers harvested Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine, oak, and madrone, leaving large heaps of debris in their wake. These abandoned slash piles increased fire hazards. “The once open forest,” resident Orson Stearns recalled, “soon became a forest of young pine and other trees, with a mass of rotten tree tops and limbs, the refuse of the waste of logging.” When they cut timber from riparian areas, the water temperatures rose sufficiently to endanger coldwater fishes. Although timber cutting was limited to lower elevations, by the end of the century loggers had largely cleared the foothills and horse teams had gouged skid roads higher into the mountains. The largest trees in rugged, inaccessible watersheds remained untouched.

By 1880, hydraulic mining in the Applegate, Illinois, and Rogue River watersheds created a new economic boom. Hydraulic miners channeled water from a ditch above the mine through a large pipe, or “giant,” to the placer site where they excavated gravels using a high-pressure stream of water shot from a nozzle, and then ran the soil and water through screens to collect the gold. The method enabled miners to handle large amounts of placer gravels in a short time and to work in areas with short mining seasons.

Merchants sold expensive equipment and supplies to the mining companies. Ditch construction, spurred by the need for additional sources of water for mining the higher terraces, demanded labor and equipment and required investors to risk massive capital. Late in the 1880s, however, as less accessible placers forced miners to work deeper and higher gravels, the investment money eventually ran out, and men turned away from the mines.

Although the economic influence of hydraulic mining in the region faded, its signs on the landscape lasted for years. Dams and diversion ditches had interfered with fish migration, and the hydraulic giants’ violent action had destroyed streamside banks, washed away soils, and caused seasonal flooding. Euro-American settlers removed the Native inhabitants whose careful management of natural resources had supported life for centuries. They reshaped the landscape in the images of the places they remembered, and in doing so, they found new ways to use and use up the region’s natural assets.

Beginning in the first decade of the twentieth century, new laws protected southwestern Oregon’s public lands, limiting residents’ former unrestricted use of the federal domain. President Theodore Roosevelt created the Siskiyou National Forest in 1906, which was later divided into six ranger districts. To the east lay the Crater National Forest—later the Rogue National Forest—established in 1907. In these forests, rangers oversaw homestead entries and trail and telephone-line construction. Annual burning in forested areas—both human-caused and natural—persisted during the early years of the century. After severe fires devastated forests in the region and throughout the West, the U.S. Forest Service mounted intense efforts to detect and control fire.

Small rural sawmills worked in the region after the turn of the century, using steam- and gasoline-powered equipment and moving from place to place to supply timber to homesteaders, orchardists, and the railroad line. “A lot of what they cut was big trees,” Wilber Milton, a logger in the Rogue River vicinity, recalled. “They cut the timber down and sold it or used it themselves and burned the stumps.”

Although most of the region’s high timberlands remained untouched by logging, large privately owned companies gradually acquired thousands of forested acres, much of it from homesteaders. Lack of roads in the high country delayed widespread logging, but entrepreneurs penetrated the heavily timbered mountains that flanked the Rogue River valley. Midwestern timber barons, who had already depleted forests in the Great Lakes region, controlled companies such as the Butte Falls Lumber Company (owned by Michigan lumbermen) and the John S. Owen Lumber Company of Wisconsin. The gradual consolidation of forested lands under common ownership provided the capital and equipment to exploit the wealth in the trees.

© Kay Atwood and Dennis J. Gray, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.