|

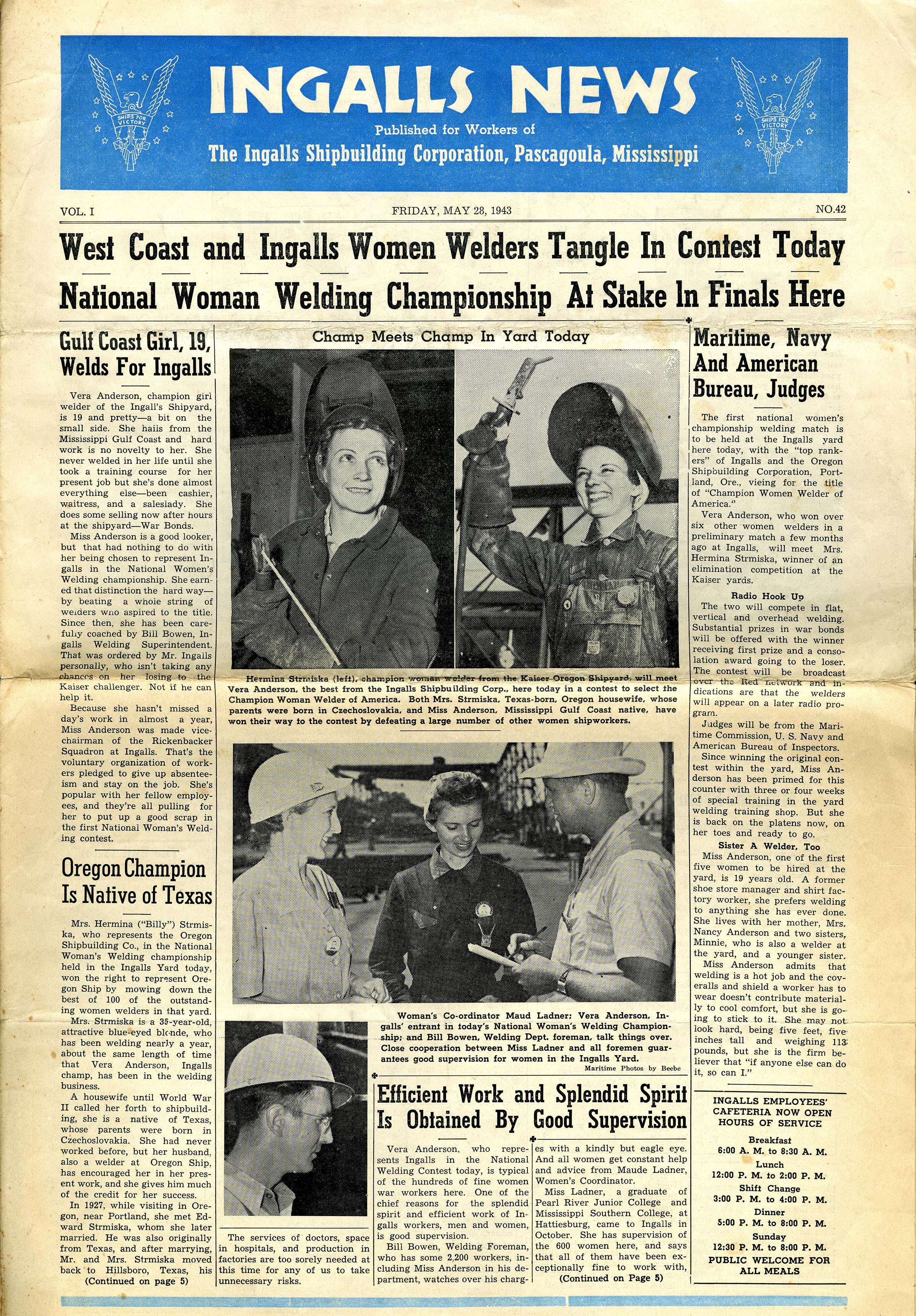

by Mary Bryan Curd Hermina “Billie” Strmiska was thirty-five when she won the Oregon Shipbuilding Welderette contest in March 1943, beating out one hundred other women welders in the standard American Bureau of Shipping Test. Her victory qualified her to compete in a national contest at Ingalls Shipbuilding Company in Mississippi. The contest was part of a national recruiting and morale-boosting effort by the shipbuilding companies to bring women into the workforce. Billie was born in Texas, and first arrived in Oregon City as a teenager, eventually working in Portland as a nanny. She married and moved to West Linn so her husband Ed could work in the sawmills. They returned to Texas, but the Depression drew them back to the Northwest as migrant pickers. When the shipyards picked up, she and Ed found jobs in the shipyards as welders. Before applying for the job, Billie enrolled in a private welding school on Foster Avenue in Portland so she could pass the welding test for the Oregon Shipyards. She got the job, joined the Boilermakers Union, and went to work fulltime. She was a quick study and mastered the three kinds of welding required to win the contest: flat, vertical, and overhead welding. After the war, women were the first to be laid off from their shipyard jobs. Some found skilled employment in the private sector, but most were forced to return to clerical, retail, and domestic work at wages far below that of their wartime jobs. Billie made enough money in the shipyards to buy a farm, and she spent her post-war years there. Her oral history about her years as a shipyard worker was taken in 1981, and it is available in the Oregon Historical Society Research Library. |

|

|

|

All images and documents come from the Hermina Strmiska collection, circa 1942-1945 |

Most of the women who worked in shipyards during World War II were taking on jobs that had been held by men. That shift in labor felt to many people like a threat to traditional gender roles. Employers, who needed women workers but did not want to create cultural and social upheaval, worked very hard to reassure people that women were keeping their femininity intact despite the "masculine" work they were doing. One of the marketing methods wartime employers used was to publish beauty shots, like these taken of Billie Strmiska in her welding uniform. It was not uncommon to see women with a welding tool in one hand and a tube of lipstick in the other in photographs distributed to employees and the public by shipyard companies.

|

|

|

The Welding Competition

The welding competition for women held in Mississippi—judged by the inspectors from the Maritime Commission, the Bureau of Ships, and the U.S. Navy—was elaborately covered by the news and entertainment media, including Movietone News, the Associated Press, and Life Magazine. Billie came in second, winning a trip to Washington, D.C., along with first-place winner Vera Anderson. The national event was recognized by Eleanor Roosevelt in her Washington Daily News column “My Day” soon after she met with the women: “This is a new occupation for women, and that is why this competition was staged, I imagine. They probably need more women welders and so this should spur the ladies on.”