- Catalog No. —

- Yasui Family Papers Coll. 949, Box 17, folder 2

- Date —

- 1953

- Era —

- 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Education, Government, Law, and Politics, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Masuo Yasui

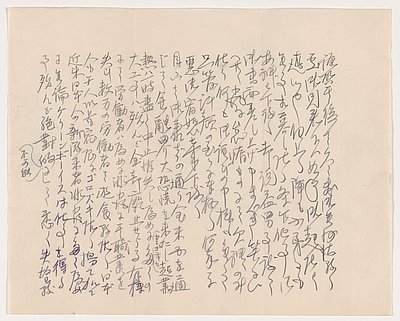

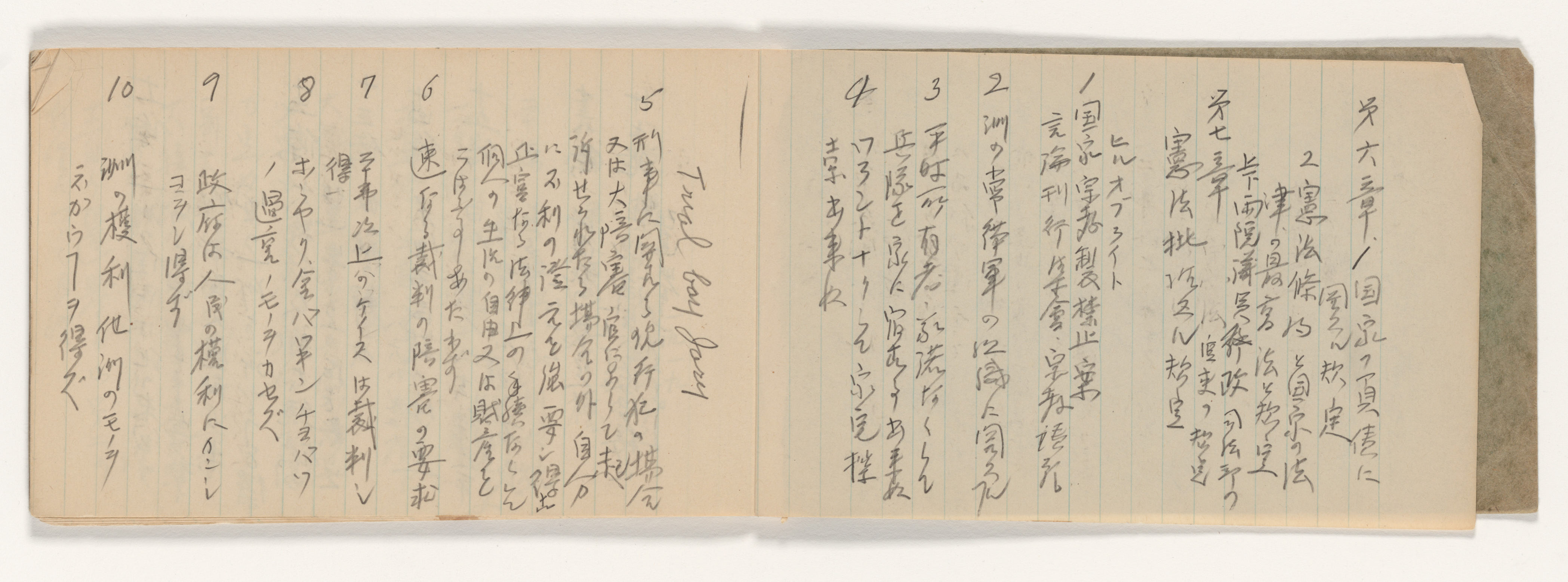

Masuo Yasui's study notes for U.S. citizenship exam, 1953

This notebook belonged to Masuo Yasui, who immigrated to the Pacific Northwest from Nanukaichi, Japan, in 1903. His careful notes are evidence of his efforts in 1953 to become a citizen of the United States. On the notebook’s pages, he describes the structure of the American system of government, on both state and federal levels, along with timelines of Oregon and national history and the names of current government leaders. He was studying for an oral test, which he would take in English before a judge to determine whether or not his citizenship application would be approved. If he answered the questions incorrectly, his decades of residency, his business success, the taxes he had paid, his civic involvement, and the fact that his children had been born and raised in Oregon would not offset a failed exam. And so he studied.

Masuo Yasui was sixteen years old when he sailed into Seattle in 1903. His older brother Taiitsuro worked for the Union Pacific Railroad in Montana, and Masuo joined him on the crew. He moved to Portland in 1905 to study and work, and by 1908 he had settled in Hood River, where he opened a store to serve the hundreds of Japanese immigrant laborers who worked in the valley. Another brother, Renichi Fujimoto, joined him. For three decades, Yasui and his family worked in the store and also in real estate, farming, and labor contracting, and he often was a translator between Japanese- and English-speaking residents.

Yasui was among the first Issei in Oregon to be arrested after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, when community leaders who maintained ties to Japan were deemed by the federal government to be “dangerous to the public peace and safety.” He spent the majority of the war in an internment camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The rest of his family—and most other people of Japanese descent, regardless of their citizenship status—were incarcerated in camps throughout the West. They lost their homes, businesses, and property, and they were harassed and threatened when they returned to their communities in 1945-1946 when the internment order was suspended. (Executive Order 9066 was not rescinded until 1976 by President Gerald Ford.)

When Masuo Yasui and his wife Shidzuyo returned to Oregon, they avoided Hood River, which was notorious for being anti-Japanese during and after the war. They settled in Portland, and it was there that they began the process of becoming U.S. citizens, which required dedication and hours of study, as Yasui’s notebook documents.

U.S. citizenship for Japanese nationals had been nearly impossible for decades. When Japanese men began sailing to the West Coast to find work during the 1880s, the relationship between the U.S. and Japan had been tenuous but optimistic. Both wanted open trade, and both wanted their Pacific territories acknowledged and respected. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1858 had opened Japanese ports to American traders, and a treaty in 1894-1895 kept those trade doors open with the stipulation that the U.S. allow Japanese nationals to immigrate freely to America subject to the same civil rights as U.S. citizens. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had created a labor shortage when it stopped the flow of Chinese workers into the country, and Japanese men filled much of the gap. It was during that period of immigration that Masuo Yasui and male members of his family had traveled to Montana.

But the anti-Asian nativism that plagued the West Coast did not abate, and in 1906 San Francisco segregated Japanese children from their peers, which compelled the Japanese government to accuse the U.S. of breaking the treaty. The possibility of war in the Pacific became a concern for President Theodore Roosevelt, and the contentious relationship among Japan, China, Korea, and Russia made U.S. interests—including Hawaii, the Philippines, and Guam—vulnerable. The president’s effort to calm things resulted in the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, which slowed the flow of labor from Japan but allowed family members to immigrate.

Between 1907 and 1941, many Japanese immigrants advocated and sued for naturalized citizenship in the United States, but their efforts were nearly always thwarted by anti-Asian organizations and legislators. The enmity was not universal, however, and Japanese immigrants in Oregon created strong and cohesive communities, particularly in Portland and Hood River, and lived peaceably with white neighbors.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 ended that feeling of community for thousands of West Coast residents. Fueled by fear and racism, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the FBI to arrest “suspicious” Japanese nationals without due process. He followed this with Executive Order 9066 in 1942, which incarcerated over a hundred thousand Japanese and Japanese Americans men, women, children on the West Coast. For those with Japanese heritage, regardless of their citizenship status, their basic civil rights, guaranteed by the Constitution, had been stripped from them.

The restriction on American citizenship for Asian immigrants remained firmly in place during the early post-war years, and Japanese immigrants remained excluded and unprotected with no opportunity to be naturalized under U.S. law. That changed in 1952, when the Immigration and Nationality Act—known as the McCarran-Walter Act—passed Congress, lifting the restrictions on Asian immigration and citizenship. The Yasuis immediately began the process of becoming citizens.

Masuo, fluent in English and Japanese, led study sessions for the exam part of the application process. He may have used published “Americanization” guides to inform those sessions, which likely included oral practice exams with such questions as “Who is the Father of our Country?” and “How many representatives from Oregon are allowed in Congress?” His work paid off. By 1953, both he and Shidzuyo had passed the exam and become citizens. Less than fifteen years later, more than 40,000 first-generation Japanese immigrants in the U.S. had done the same.

Further Reading

Yasui, Barbara. "The Nikkei in Oregon." Oregon Historical Quarterly 76.3 (September 1975).

Johnson, Daniel. "Anti-Japanese Legislation in Oregon." Oregon Historical Quarterly 97 (1996).

Nagae, Peggy. "Asian Women: immigration and citizenship in Oregon." Oregon Historical Quarterly 113 (2012).

Hong, Jane. "Immigration Act of 1952." Densho Encyclopedia, 2024.

Kessler, Lauren. Stubborn Twig. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2005.

"42 Japanese Prepare for Citizenship (in Hood River)." Portland Oregonian, April 27, 1953.

Written by A.E. Platt, © Oregon Historical Society, 2024.

Related Historical Records

-

Japanese Evacuee Tops Sugar Beets

This 1943 Oregonian photograph shows a Japanese American “evacuee” topping sugar beets in Nyssa, a small town on the Idaho state line in Malheur County. On February 19, …

-

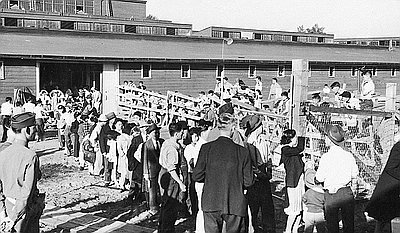

Japanese Evacuees, Portland Assembly Center

In May 1942, Portland-area Japanese and Japanese Americans—both Issei (first generation) and Nisei (second generation) —were evacuated to hastily constructed temporary living quarters in the Pacific International Livestock …

-

Letter from Masuo Yasui to Taiitsuro Yasui and Renichi Fujimoto, December 12, 1907

Full letter. Transcription in Japanese. English translation (partial) This letter, which has been translated into English, was written by Masuo Yasui in 1907, two years after he …