Japanese Forced Removal and Incarceration

Portland lost thousands of potential workers in the spring of 1942, when its residents of Japanese descent, were forcibly removed and incarcerated. During the war, 120,000 U.S. residents of Japanese ancestry were moved from the West Coast to concentration camps. The Oregonian argued cautiously in December 1941 that individual Japanese were loyal citizens, until proven otherwise. In late January 1942, at a large public meeting at the Shattuck School, City Commissioner Fred L. Patterson and representatives of local newspapers and the Red Cross reaffirmed the loyalty of local Japanese and urged them to volunteer for war work. Speakers from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), including James Y. Sakamoto, editor of Seattle’s American Courier, demonstrated how local Japanese were contributing to their country.

In mid-May 1942, however, local Japanese Americans were required to report to the North Portland Assembly Center, which by June 7, held almost four thousand people. Some left for seasonal farm work in eastern Oregon, while others volunteered to go to Tule Lake to staff a maximum security center under construction. To sustain morale, its newsletter, the Evacuazette, catalogued new arrivals; listed recreational activities, including an Obon festival, movies, and dances; and informed internees of the changing rules of center life.

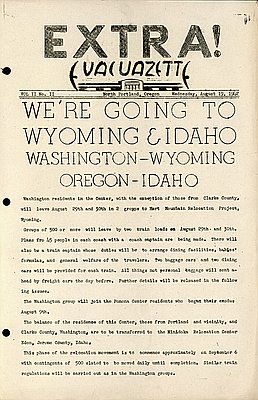

The August 19 issue of the Evacuazette finally informed residents of their destinations. Those from Washington State would be incarcerated in Heart Mountain, Wyoming, on August 29, while those from Portland and Clark County, Washington, would leave on September 6 for Minidoka, a 17,000-acre plot owned by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in southern Idaho. The editor-in-chief, Yuji Hiromura, had argued that the era of the community’s immigrant leadership had ended, and now the American-born citizens had to assume control. He noted in a subsequent issue, “though for many of us indignation runs high and disappointment dampens our anticipation of future activities, we must realize that a cooperative spirit must be maintained.”

The majority Japanese and Japanese Americans remained incarcerated for the remainder of the war, though some did leave the camps for military service or to pursue educational or employment opportunities. Those Japanese who returned to Portland following the war faced prejudices and as a result, some chose to resettle in other areas of the state or country. In eastern Oregon, Ontario gained a strong Japanese American community, which increased from 137 in 1940 to 1,170 in 1950.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Japanese Evacuee Tops Sugar Beets

This 1943 Oregonian photograph shows a Japanese American “evacuee” topping sugar beets in Nyssa, a small town on the Idaho state line in Malheur County. On February 19, …

We're Going to Wyoming & Idaho

The August 1942 special edition of the Evacuazette, a newspaper published for people detained at the Portland Assembly Center in North Portland, provided news about their upcoming relocation …

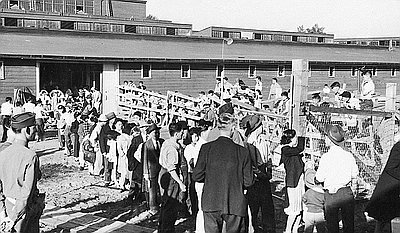

Japanese Evacuees, Portland Assembly Center

In May 1942, Portland-area Japanese and Japanese Americans—both Issei (first generation) and Nisei (second generation) —were evacuated to hastily constructed temporary living quarters in the Pacific International Livestock …