- Catalog No. —

- Mss1585_b9f5

- Date —

- c.1950

- Era —

- 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Black History, Education, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society Research Library

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Portland Urban League Collection

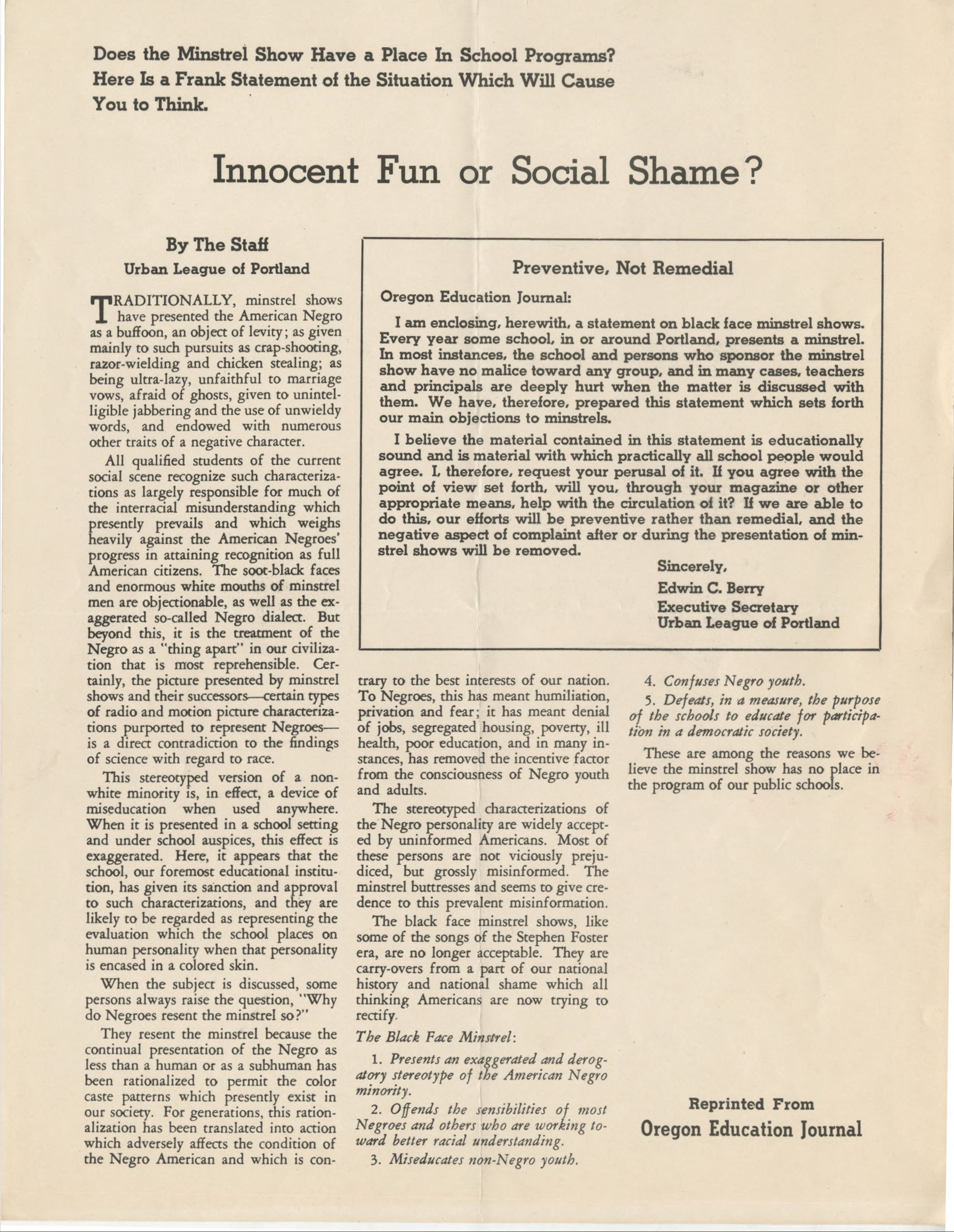

"Innocent Fun or Social Shame?"

This document was created for school administrators by the Urban League of Portland sometime in the 1950s in an effort to stop minstrel, or blackface, productions in schools. The head of the Urban League, Edwin (Bill) Berry, makes a personal appeal to educators. In a section titled “Preventive, Not Remedial,” he explains how difficult it is to talk with school leaders after they have staged blackface productions, as the organizers become defensive, claim ignorance, and excuse the performance. Most importantly, Black students had already endured the spectacle ,and white students had become more comfortable with racist stereotypes. The “remedial” approach to ending minstrels, Berry concludes, is ineffective. Instead, he argues for a “preventive” approach—that is, providing information about the racist history of blackface and its effect on Black students may prevent schools from staging minstrels and avoid having to confront or mitigate their effects.

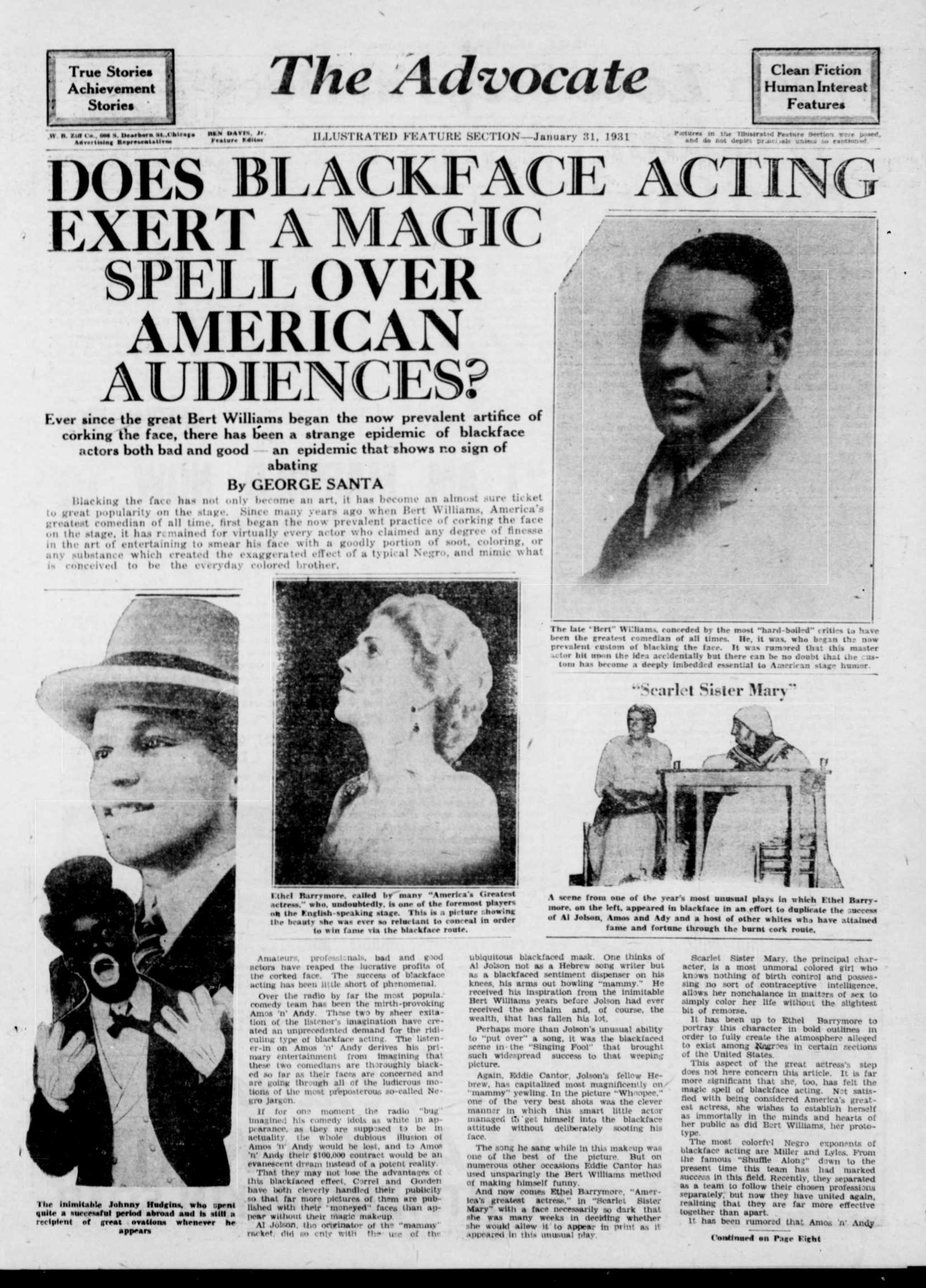

Minstrel shows, with the skin of white performers darkened with burnt cork or shoe polish, became popular in the United States during the 1830s. Actors mimicked enslaved African Americans for entertainment, and they dressed and behaved according to insidious and popular stereotypes that depicted Blacks as lazy, superstitious, and ignorant. Thomas Dartmouth Rice was perhaps the most famous minstrel in America, having developed the character of Jim Crow, who was so well known that it became associated with a century of codified racial segregation. Rice’s Jim Crow entered the lexicon as a synonym for enduring racism in the U.S.

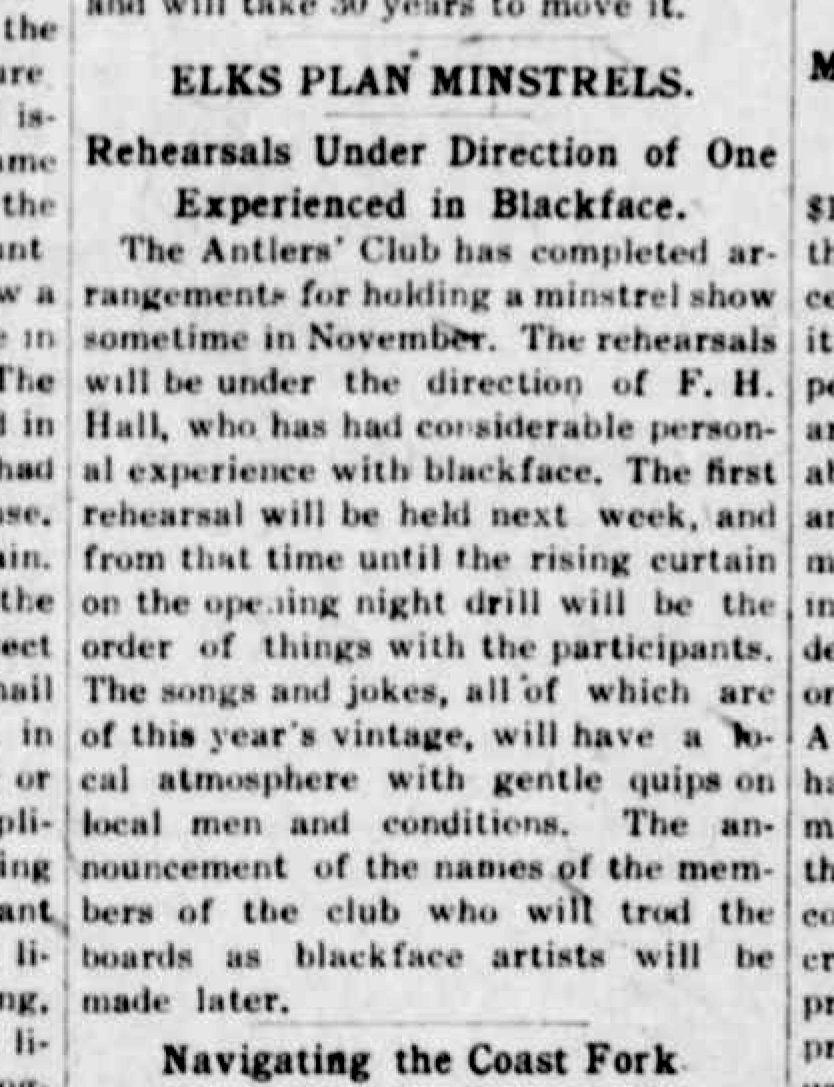

Minstrelsy was popular in Oregon beginning as early as the 1860s. Troupes stopped in towns throughout the state and were among the earliest performers in Oregon theaters. The California Minstrels, a perennial favorite, performed in Grants Pass, Eugene, and Portland, among other towns, during the nineteenth century, and blackface performances continued in the state well into the twentieth century, despite public admonition by Black newspapers such as the Advocate. Public schools almost always included blackface in student performances throughout those years, with no acknowledgment of the negative effects they had on Black students. Fraternal and garden clubs entertained blackface, as did employees at company events and retreats, as late as the 1960s.

The Urban League of Portland was established in 1945, with Berry as its director, and this document is just one of many resources on race he helped produce for educators. Oregon has been overwhelmingly white by legislative design since its settlement period, and the state has been slow to address and ameliorate its history of racial discrimination and inequality. Local Black advocates and advocacy groups, including the Urban League, brought the Civil Rights Movement to Oregon and instigated important changes across public institutions. As a result, it has become common knowledge that blackface performances are unacceptable.

And yet, this document still has relevance in a state where racial inequity and insensitivity persist. In 2021, a white elementary teacher in Newberg, Oregon, walked into her classroom wearing blackface in an attempt to invoke Rosa Parks in a protest against the state’s COVID vaccination mandates. The instances of white people “wearing” stereotypical versions of blackness for their own amusement or purposes continue.

List of newspaper articles below:

1. "Elks Plan Minstrels" The Cottage Grove Sentinel, September 22, 1911.

3. "Plans Laid for Legion Benefit Show." The Bonneville Dam Chronicle, November 11, 1938.

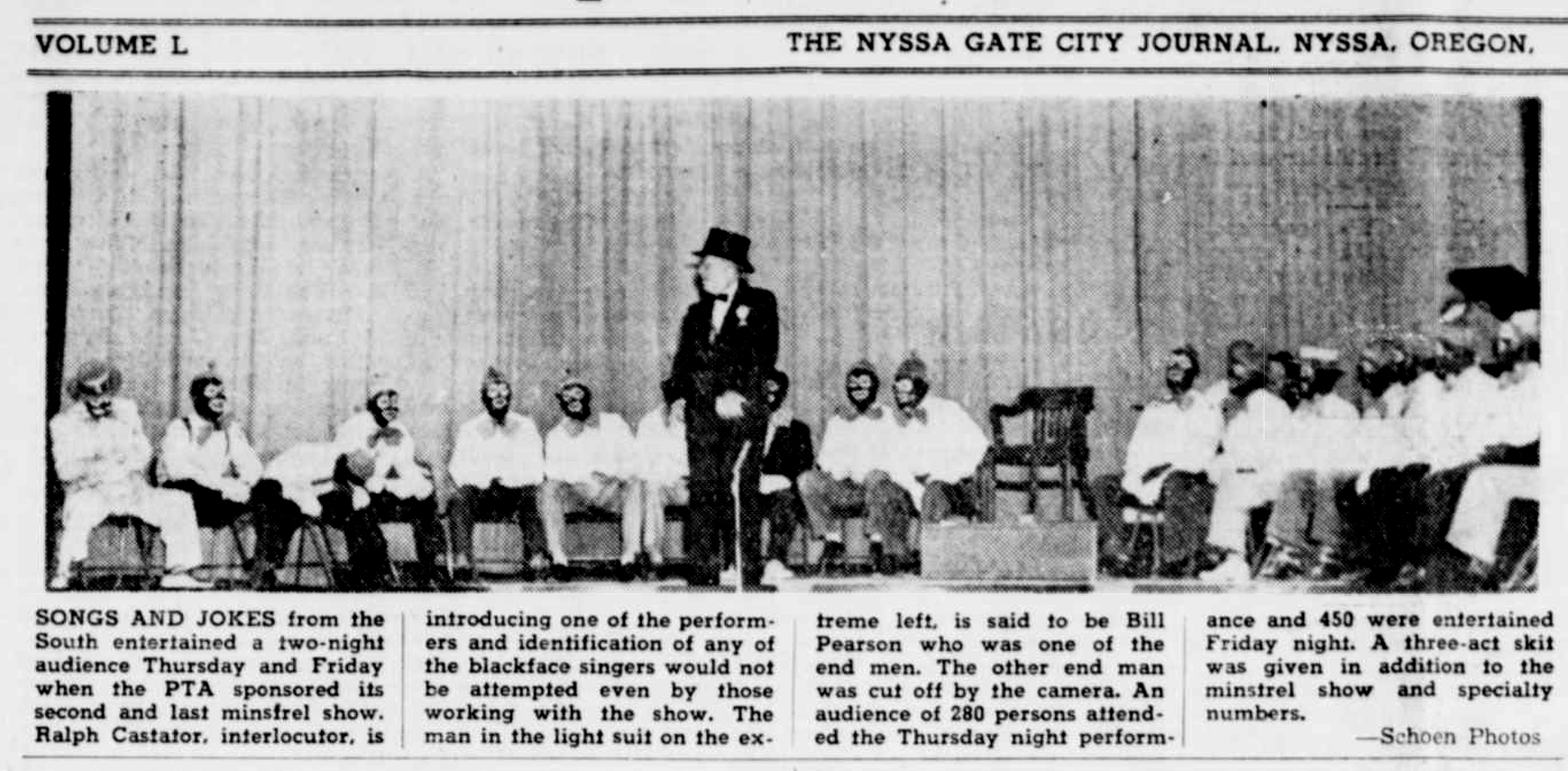

4. PTA performance. Nyssa Gate City Journal, March 3, 1955.

5. "Past Worthy Matrons Honored at Star Meet." The Mill City Enterprise, February 13, 1958.

6. "AHS Presents Minstrels Tonight and Saturday." Ashland High School Rogue News, March 30, 1962.

7. "Investigation of UO law professor a teachable moment." East Oregonian, November 9, 2016

Further Reading

Neklason, Annika. "Blackface Was Never Harmless." The Atlantic, February 16, 2019.

Thompson, Ayanna. Blackface. New York City: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

Santa, George. "Does Blackface Acting Exert a Magic Spell Over American Audiences?" The Advocate, January 31, 1931.

"Cleveland Tackles Racism." The Portland Observer, May 1, 2009.

Malveaux, Julianne. "Politically Correct, or Perfectly Civil." Skanner, October 31, 2018.

Written by A.E. Platt, © Oregon Historical Society, 2021

Related Historical Records

-

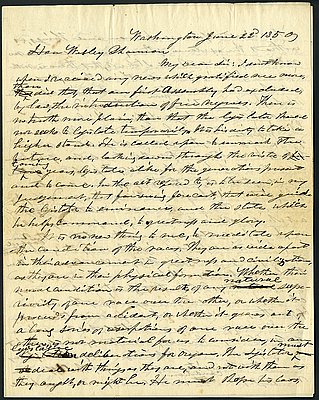

Letter from Samuel R. Thurston to Wesley Shannon, June 22, 1850, regarding Oregon's Black exclusion laws

Click here for full letter. Click here for transcript. This letter was written by Territorial Representative Samuel Thurston in 1850 to his friend and political ally Wesley …

-

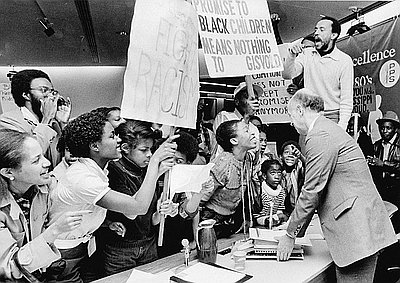

African American Community Protests School Board

Black United Front leader, Ron Herndon, stood on a desk at this 1982 protest, leading members of the African American community in chants of “You’d better go home because …

-

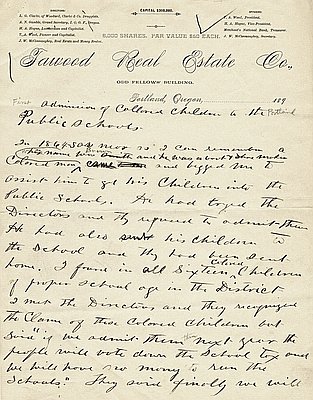

"Admission of Collored [sic] Children to the Public School"

Thomas Alexander Wood (1837-1904) was a white Oregon pioneer, a veteran of the Indian wars, and a Methodist clergyman. In these reminiscences he recalled the aid he provided …