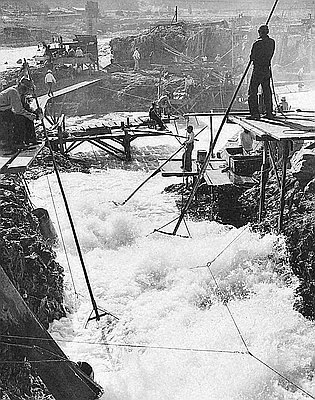

This photograph of various representatives of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was taken during negotiations for financial compensation arising from the inundation of fishing sites at Celilo Falls by the yet to be completed Dalles Dam. During negotiations, it was typical of the Yakama to outnumber the Army Corps. This photograph shows at least eleven tribal representatives, compared to six Army Corps counterparts.

Although discussions between the Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs, Nez Perce, unaffiliated Columbia River Indians, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began over the proposed construction of The Dalles Dam as early as 1945, the Army Corps did not enter into negotiations with the tribes in earnest until Congress failed to allocate construction funds for the dam in 1952. The delay was largely due to the Army Corps’ failure to make headway in resolving Indian claims to “usual and accustomed” fishing sites at Celilo Falls.

The participation of the Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Nez Perce tribes in negotiations was not looked upon favorably by the Yakama’s tribal council, who in 1951 passed a resolution claiming that they alone held treaty-based fishing rights at Celilo Falls. From their perspective, Celilo Falls was not a “usual and accustomed” fishing site for the Umatilla. Rather, the Yakama tribal council believed that the Umatilla fishers at Celilo were their guests. And while the Yakama conceded that Celilo Falls was once a “usual and accustomed” site for the Warm Springs tribes, they considered their claim nullified based upon an 1865 treaty that relinquished the latter tribes’ treaty-based fishing rights for $3,500 (the treaty was long held to be the result of dishonest swindling by a federal agent, since signatories believed they were signing a permit to allow them to move freely outside of the reservation). The Army Corps, however, considered both tribes to hold valid—though arguable—claims to fishing sites at Celilo.

Despite disagreements over claims between the Yakama, Warm Springs, and Umatilla, leaders from all three tribes agreed that the Nez Perce did not have a valid claim to Celilo Falls. For a time, the Army Corps of Engineers agreed. But, in the end the Nez Perce were able to apply enough political pressure on the Army Corps to receive compensation for the eventual drowning of Celilo Falls in 1957.

When negotiations were completed the Army Corps had provided compensation totaling $26,888,395: $15,019,640 to the Yakama; $4,4451,784 to the Warm Springs; $4,616,971 to the Umatilla; and $2,800,000 to the Nez Perce. Importantly, none of the tribes relinquished their treaty-based fishing rights to fish at their “usual and accustomed” fishing areas on the Columbia River. Rather they accepted the financial settlements as direct compensation for the loss of fishing sites. Today, all four tribes continue to exercise their rights to fish on the mainstem of the Columbia River—though their fishing gear and strategy has been adapted to fish reservoirs instead of rapids and falls.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.