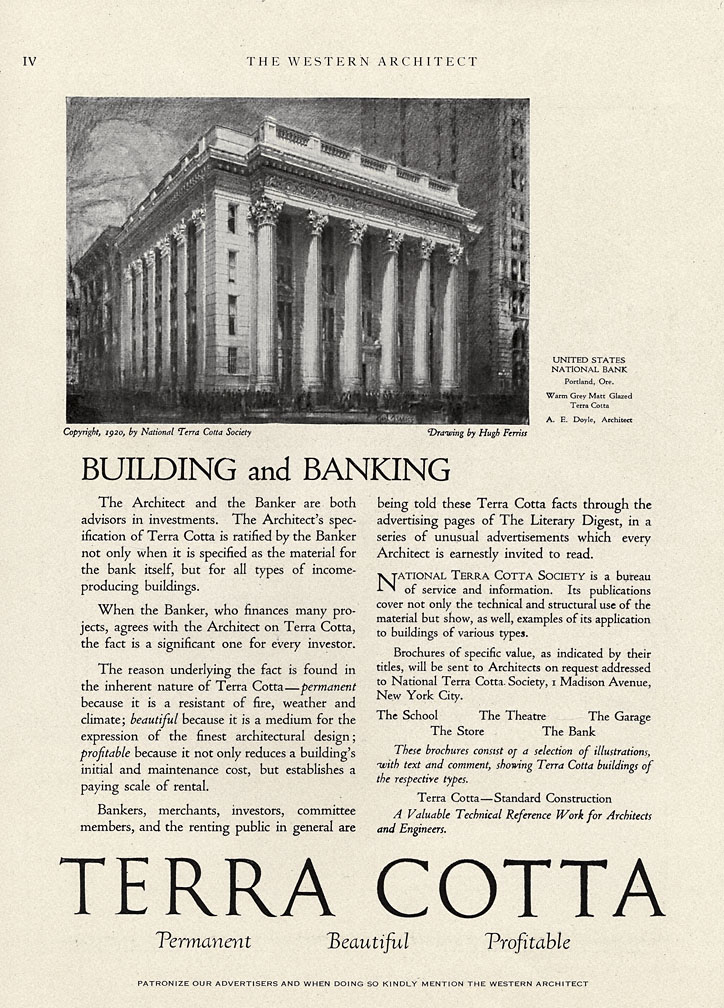

An advertisement for the building material terra cotta depicts the first section of the United States National Bank building in Portland as drawn in 1920. The bank was designed by Albert E. Doyle, whose architectural work dominated Portland’s commercial core in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

In his Architectural Guidebook to Portland (2001), Bart King described the bank as “a terra-cotta temple acknowledging the power of the dollar, and an impressive place of worship it is.” Sited across Stark Street from the Greek Revival headquarters (1916) of its once-arch rival First National Bank, the United States National Bank was built in two segments, completed in 1917 and 1923. Structurally the building is of reinforced concrete and steel, with a base faced in granite. The , pilasters, cornices, and other details are formed of terra cotta. Terra cotta is made of clay that is shaped, glazed, and fired to produce building elements that are durable, fireproof, easily applied, and available in colors. The new high-rise steel-framed office buildings of the early twentieth century were often clad in glazed terra cotta, as were department stores, theaters, and hotels.

Architect A. E. Doyle (1877-1928) made a major impression on Portland’s built environment in a short period of time. In 1891, at age 14, Doyle became an apprentice in the offices of Whidden & Lewis, the city’s leading design firm. Doyle later studied architecture at Columbia University, and returned to Portland to open a partnership with William B. Patterson in 1907. On his own after 1915, Doyle was responsible for the design of numerous landmark structures: the Benson Hotel, Meier & Frank and two other major department stores, Reed College, the Central Library, and the Pacific Building. All of these buildings required a mastery of classical design elements in a variety of styles, as well as knowledge of new building technologies such as the steel frame and reinforced concrete.

Earlier in his career, Doyle had demonstrated a mastery of design in the wooden tradition and in smaller residential structures. In the northern Oregon beach community of Manzanita, at the base of Neahkahnie Mountain, Doyle created several small shingled beach cottages, including one for Portland librarian Mary Frances Isom (1912) and for artist Harry Wentz (1916). These cottages have been cited as forerunners of the Northwest Regional style. Doyle was the mentor of Pietro Belluschi, who became a notable proponent of the Northwest Regional style in the 1930s and 1940s. Belluschi eventually also took over Doyle’s practice; as had been the case with Doyle, Belluschi’s abilities in designing in wood did not preclude his later success with new materials and new esthetics as well.

Further Reading:

Ferriday, Virginia Guest. Last of the Handmade Buildings: Glazed Terra Cotta in Downtown Portland. Portland, Oreg., 1984.

Written by Richard Engeman, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.