- Catalog No. —

- S 2-2528

- Date —

- 1998

- Era —

- 1981-Present (Recent Oregon History)

- Themes —

- Arts, Folklife, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society Folklife Program

- Regions —

- None

- Author —

- Leila Childs

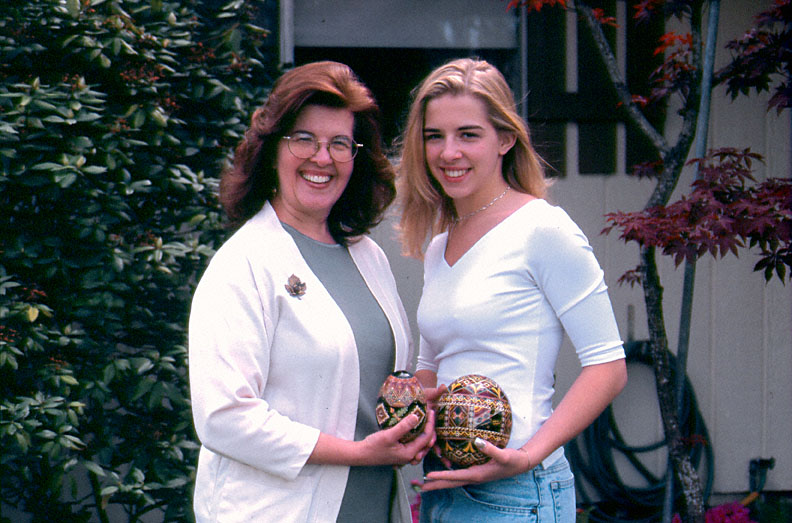

Ukrainian Pysanky

This photograph of Hedy Connelly (left) and her daughter, Kaleene Connelly (right), posing with their Ukrainian pysanky eggs was taken by Leila Childs at the Connelly’s Grants Pass home in 1998. At the time, Kaleene was undergoing formal training in pysanky art from her mother through the Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program of the Oregon Historical Society Folklife Program. Pysanky, translated as “written eggs,” are a Ukrainian art form with roots dating back thousands of years. Although leaders of the Christian church have historically embraced the tradition—making it part of Easter celebrations—the pysanky symbols have pagan roots connected to sun worship. Many traditionally-minded Ukrainians continue to integrate pysanky into family and community celebrations like weddings and births.

Hedy Connelly was born in Madison, Wisconsin in 1947 and moved to Grants Pass, Oregon in 1970. Although she watched her family elders make pysanky throughout her entire life, she didn’t begin doing pysanky until she was twenty-five. Since then, she has developed a well-earned reputation as a master pysanky artist. Today she is well-known for her use of the intricate Ukrainian rose pattern displayed on most of her eggs. According to Hedy, “the most important thing is that these [pysanky] come from the heart. It isn’t a matter of everything staying the way it was. This is a process of people and hopes and wishes and dreams that have unfolded through the years. It will be interesting to see what pysanky look like a hundred years from now. They’ve come so far.”

Hedy creates designs on the eggs by applying layers of beeswax patterns to the surface of the egg with a tool called a kistka. After each layer of wax layer is applied, she dips the egg into a natural dye, which fixes color everywhere but where the beeswax was applied. Once she applies the final layer, she uses the flame of a candle to melt the wax off the surface of the egg, gently wiping it away. Once the blackened wax is removed, the true colors of the pysanky are revealed. Historically, people applied oils to finished eggs to make them shine. Today, artists use varnish.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.