- Catalog No. —

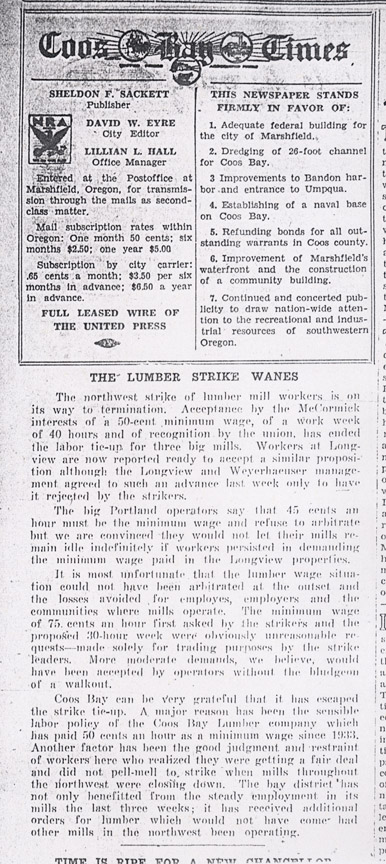

- Coos Bay Times, May 29, 1935

- Date —

- May 29, 1935

- Era —

- 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II)

- Themes —

- Government, Law, and Politics, Labor, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Coast Southwest

- Author —

- Coos Bay Times

The Lumber Strike Wanes

This editorial appeared in the Coos Bay Times on May 29, 1935. It describes the 1935 lumber strike, one of the largest labor strikes in Pacific Northwest history.

During the first years of the Great Depression almost two-thirds of Oregon’s timber workers lost their jobs, and many of those who remained at work experienced wage cuts. In the spring of 1935 members of one of the region’s largest timber workers union, the Sawmill and Timber Workers Union, voted to strike if they did not receive an increase in the minimum wage, a thirty-hour work week, overtime and holiday pay, seniority rights, and union recognition. When mill and logging company owners refused to concede to the union’s demands, an estimated 30,000 timber workers went on strike. About half of the region’s mills, furniture and box factories, and logging operations were shut down.

The lumber strike was strongest in Washington, where most of the state’s largest mills were idled. Although most of the mills, logging camps, and wood product factories in the Portland area and on the lower Columbia River were shut down, most of the rest of Oregon’s lumber operations continued to operate throughout the duration of the three-month strike.

Many of the state’s newspapers came out against the strike. The Oregonian, the state’s largest paper, called the strike “futile,” while the Coos Bay Times argued that “what the northwest strike will do is divert the small volume of available lumber business to Canada and to the pine districts of the southern states. It cannot ‘break’ the operators; they are quite uniformly broke or badly bent as things stand.” In the editorial reproduced here, the Coos Bay Times praises local lumber workers for not striking. They argue that local workers did not strike because the Coos Bay Lumber Company paid a fair wage. They also note that the Coos Bay area actually benefited from the strike since they received orders that could not be filled elsewhere in the region.

Despite the editorial’s declaration that the strike was waning in late May, the strike remained strong for several more weeks. Most of the major lumber operations in Portland and on the lower Columbia River remained closed until late July. Although striking workers gained a modest pay raise, a forty-hour work week, and, in some cases, union recognition, most of their demands were not met.

Further Reading:

Lembcke, Jerry, and William M. Tattam. One Union in Wood: A Political History of the International Woodworkers of America. New York, N.Y., 1984.

Written by Cain Allen, Oregon Historical Society, 2006

Related Historical Records

-

Longshoremen's Strike of 1934

This photograph of the 1934 waterfront strike shows Portland police escorting “scabs” through picket lines outside a hiring hall, a building used by companies to hire workers. During …

-

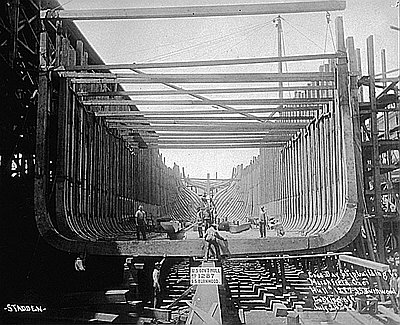

Coos Bay Shipbuilding Company

This photograph of the construction of the S.S. Burnwood in Marshfield (later renamed Coos Bay) is from a scrapbook that belonged to James Polhemus, the manager of the …

-

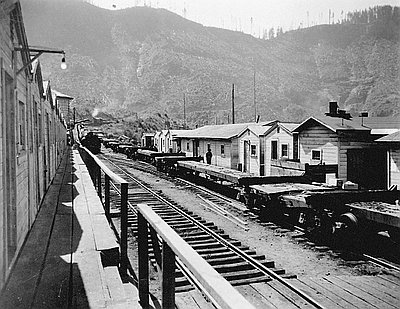

Camp Two, Coos Bay Lumber Company

A moving community of loggers is depicted in this 1930 photograph. From the 1890s through World War II, major logging operations in Oregon were railroad-based, with trackage extending …