In 1903, the Oregon Historical Quarterly reprinted this article, which appeared in the Reveille, a St. Louis, Missouri, newspaper, on October 21, 1844. The article is based on a letter that provided a short account of the “Cockstock Incident,” which occurred in Oregon City on March 4, 1844.

The Cockstock Incident was named for a man known as Cockstock, a Molalla who was often misidentified as a Wasco. The incident originated with a property dispute involving Cockstock and two African American residents of Oregon; George Winslow (also known as Winslow Anderson) and James D. Saules. Sometime in 1843, Winslow hired Cockstock as a temporary laborer on his farm, work for which Cockstock would receive a horse. However, before Cockstock completed his work, Winslow sold the horse to Saules. Upon learning of the sale, Cockstock became angry and confiscated the horse. He continued to make threats against both men for the next several months. By mid-February 1844, both men feared for their life and urged the U.S. sub-Indian agent for Oregon, Elijah White, to make arrangements to remove Cockstock from the Willamette Valley. Saules notified White that he was prepared to defend himself by force of arms if necessary.

White made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Cockstock in late February and early March, 1844. The conflict finally reached a head on March 4, when Cockstock and five companions made a show of force in Oregon City. The next day a skirmish erupted between Cockstock’s group and residents of Oregon City after the Indians returned to the settlement. In the clash, Cockstock was mortally wounded, as were two settlers, George LeBreton and Sterling Rogers.

In the aftermath of the Cockstock Incident, sub-Indian Agent White was able to prevent retaliatory action by the Wascos, residents of the Columbia Gorge, by offering presents to Cockstock’s widow. However, the conflict heightened fears among the settler population of Indian attacks and of potential social disruptions owing to the presence of free Blacks in Oregon. Concerns about an inter-racial Indian-Black alliance against the white settlers increased following an additional conflict involving James Saules. In a dispute with a white settler, Charles E. Pickett, Saules allegedly threatened to “incense the Indians” against Pickett.

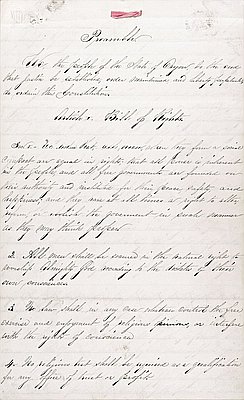

Such concerns subsequently led members of the Oregon Provisional Government to adopt the region’s first Black exclusion law in June 1844. The law required free Blacks to leave Oregon within two years of their arrival. If they did not, they would be subject to arrest and a public whipping of “not less twenty nor more than thirty-nine” lashes. Although this law was later amended, and finally repealed in July 1845, the territorial government passed a new black exclusion law in September 1849. It would be become the basis for the Black exclusion law included in the Oregon state constitution of 1859.

Further Reading:

McClintock, “James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Exclusion Law of June 1844.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 1995: 121-130.

Taylor, Quintard. “Slaves and Free Men: Blacks in the Oregon Country, 1840-1860,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 83, 1982: 153-170.

Written by Melinda Jette, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.