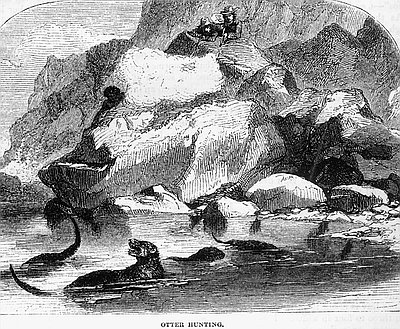

This engraving is one of the illustrations included in Charles M. Scammon’s The Marine Mammals of the North-Western Coast of America, published in 1874.

The sea otter (Enhydra lutris) played a pivotal role in the history of the Northwest Coast beginning in the late eighteenth century. At that time, sea otters were present across a vast region stretching from the Sea of Japan in the North Pacific to the Sea of Cortez in Baja California. This small marine mammal, a member of the weasel family, inhabited the kelp beds of the coastal areas, feeding on starfish, mollusks, and sea urchins. By the late eighteenth century, a market for sea otter furs had developed in northern China owing to the tastes of the Manchu upper class, who prized the furs for their warmth and especially luxurious appearance. What distinguished the otter pelts from other furs was the density, thickness, and lustrous quality of the animals’ hair, characteristics resulting from their lack of insulating body fat.

The Russians were the first Europeans to exploit the sea otter, beginning in the 1740s. Over the next several decades, Russian entrepreneurs known as promyshlenniks outfitted trading expeditions to Alaska, beginning in the Aleutian islands and moving progressively eastward to the Gulf of Alaska. British and American entrepreneurs entered the sea otter trade on the Northwest Coast in the mid-1780s. The official account of Captain James Cook’s expedition to the Northwest Coast, published in 1784, had sparked interest in the trade since it noted the high returns that could be garnered for sea otter skins in China. The British and American entrepreneurs competed aggressively in the early years, but by the 1790s, American ships hailing from Boston came to dominate the maritime fur trade on the Northwest Coast. This dominance was the result of several factors. Russian trading efforts were hampered by the long supply lines between their bases in Alaska and cities in eastern Russian, and by the fact that the main Chinese port of Canton was closed to Russian traders. British vessels also suffered from British trade practices that forced them to obtain licenses from the South Sea Company and the East Indian Company. In contrast, the Americans enjoyed open access to the Canton markets and a shorter sailing time on the trade triangle from Boston to the Northwest Coast, to China, and back to Boston.

From the 1790s and through the 1810s, scores of British, Russian, and American vessels plied the Northwest for sea otters, trading with various Native groups throughout Alaska, British Columbia, and parts of Washington and Oregon. As over-hunting depleted one region of its sea otter population, the fur trade would move on to another area. After 1810, the sea otter trade slowly diminished throughout the Northwest Coast. By the 1840s, the once plentiful sea otters had been driven to the brink of extinction. In the late twentieth century, protective legislation, and the concerted efforts of marine biologists, conservationists, Native groups, and lovers of the sea otter stimulated the recovery of sea otters in Pacific Coast waters.

Written by Melinda Jette, © Oregon Historical Society, 2003.