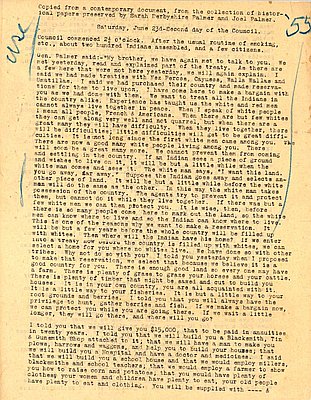

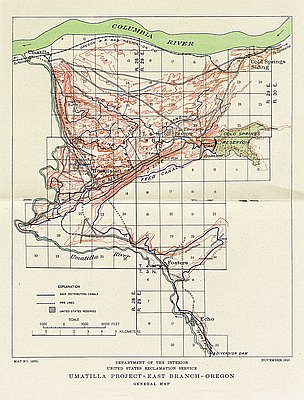

This excerpt from an 1874 report by N.A. Cornoyer, agent for the Umatilla Indian Reservation, describes the development of a new geography of Native identity in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Prior to white resettlement of the Columbia Plateau, the group identities of Native peoples were centered primarily on the village and the extended family. Upon the negotiation of treaties in the 1850s, however, federal agents lumped disparate bands together in order to more effectively gain control over Indian land and resources. The treaties resulted in the consolidation of formerly independent groups onto reservations, sometimes quite distant from their traditional territories.

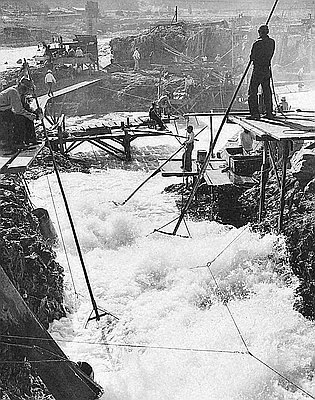

Many Native people resisted this imposed geography, however, refusing to relocate to reservations and continuing to occupy traditional village and resource procurement sites. An 1870 report by the Umatilla agent noted that about half of the Indians party to the 1855 Walla Walla treaty were still living along the Columbia. The report reproduced here estimates that there were about 2,000 Indians living on the river in the mid-1870s. These river Indians, the agent claimed, were “a great drawback to the improvement of the reservation Indians.” He urged that they be placed under “proper control.”

This distinction between river Indians and reservation Indians was apparently shared by Indians and federal agents alike. Cornoyer’s report notes that river Indians considered many of the reservation Indians to be culturally assimilated. The report’s references to Smohalla, an Indian prophet and religious leader, and polygamy, a traditional Plateau practice, confirm the traditionalist orientation of river Indians during the late nineteenth century.

However, the river-versus-reservation classification simplified a complex situation. While there were differences between the two groups, social, cultural, and economic relations remained extensive, and depending on the circumstances, “river Indians” could become “reservation Indians,” and vice versa.

Further Reading:

Fisher, Andrew H. “They Mean To Be Indian Always: The Origins of Columbia River Indian Identity, 1860-1885.” Western Historical Quarterly 32, 2001.

Relander, Click. Drummers and Dreamers: The Story of Smowhala the Prophet and his Nephew Puck Hyah Toot. Caldwell, Idaho, 1956.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.