- Catalog No. —

- ARCIA 1854-465-467

- Date —

- 1854

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Government, Law, and Politics, Native Americans, Oregon Trail and Resettlement

- Credits —

- U.S. Office of Indian Affairs

- Regions —

- Southwest

- Author —

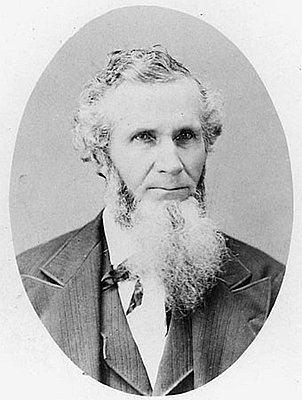

- Superintendent Joel Palmer

Report from Joel Palmer, 1854

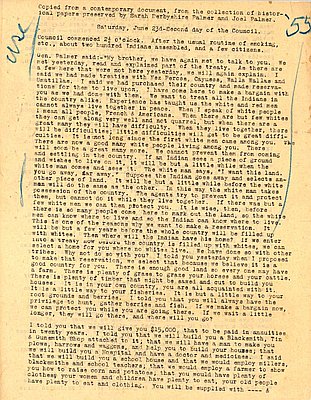

Joel Palmer, superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon, wrote this report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs on September 11, 1854. It describes a massacre that occurred at the mouth of southwestern Oregon’s Chetco River in February 1854. In the fall of 1853, a settler named A.F. Miller and several associates claimed a plot of land about a quarter of a mile from the mouth of the Chetco River, hoping to sow the seeds of a new town that would provide ferry service across the river for the miners then pouring into the country. However, the land claimed by Miller was already occupied by two Cheti Indian villages, each consisting of about twenty lodges. Prior to Miller’s arrival, the Cheti had enjoyed a monopoly on ferrying travelers across the river. Miller and the other settlers threatened them with the destruction of their villages if they did not cede the ferry site to them. To back up his threat, Miller hired several experienced Indian fighters from California.

The massacre that ensued on February 15, 1854, was one of many similar atrocities committed against Native peoples in the mining regions of northern California and southern Oregon during the mid-nineteenth century. Miller’s hired men, accompanied by several Indian allies, set fire to the village on the south bank of the Chetco, shooting the villagers as they fled from their burning lodges.

In a report several months after the massacre, Palmer reported that Miller and company murdered more than two dozen men and women in their effort to take over the ferry site. Miller was eventually arrested, but six weeks later a justice of the peace declared him innocent on the mutually exclusive grounds that there was not enough evidence and that the evidence proved that he had been justified in his violence. Palmer complained that “no act of a white man against an Indian, however atrocious, can be followed by a conviction.” Three years after the massacre, the remnants of the Cheti were forcibly removed to the Coast Reservation. Miller continued to occupy the area until at least the 1870s.

Further Reading:

Schwartz, E.A. The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980. Norman, Okla., 1997.

Stephen Dow. Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen. Norman Okla., 1971.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2003.