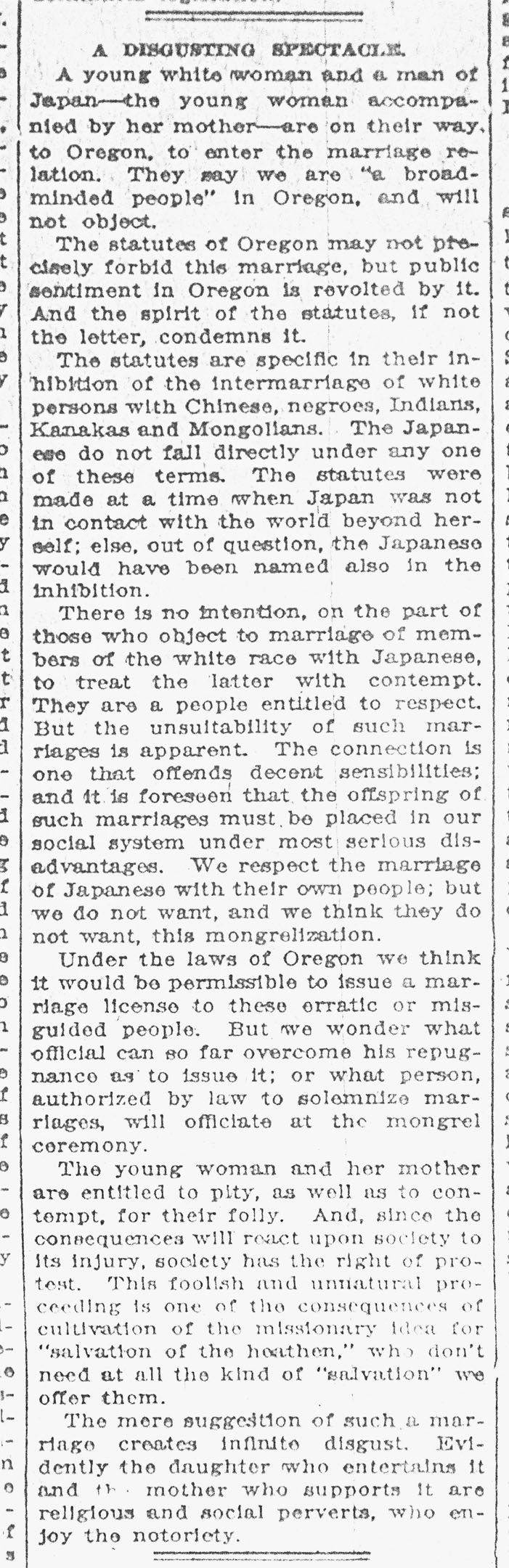

This 1909 Oregonian editorial expresses a contemptuous and biting reaction to the much-publicized marriage plans of Gungiro Aoki, Japanese, and Helen Gladys Emery, white. Having had experienced intolerance to their interracial engagement in their home state of California, the couple was en route to Portland, where they planned to wed. Days prior, front-page Oregonian articles kept Oregonians privy to the couple’s impending arrival by train and rallied a prejudiced response among the public.

By 1909, Oregon laws banning miscegenation, or interracial marriage, had already undergone revisions and additions that lengthened the list of racial groups that could not intermarry with whites. A law passed in 1862 named only whites and Blacks, but an 1866 law broadened the list to include Native Americans, Chinese, and native Hawai’ians. An 1893 law expanded the list further, adding “Mongolians”—a term used by nineteenth-century anthropologists to encompass all people from Asia.

In an article preceding this editorial, the Oregonian noted that some Japanese immigrants denied being classified as Mongolian. The ambiguity of the racial terminology caused some Oregonians, like the author of this editorial, to fear that the Aoki-Emery marriage had legal basis in Oregon, despite stern public comments by the county clerk that a marriage license would be refused to the couple.

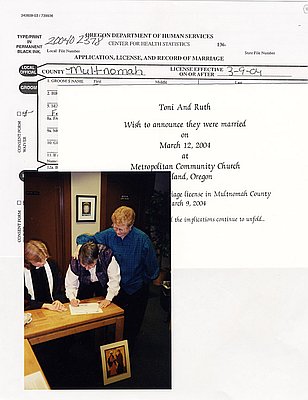

Having learned en route that the same intolerance from which they were fleeing awaited them in Portland, the couple decided to marry in Washington, where there were no laws banning interracial marriage. The couple’s failure to appear outside Portland’s Union Station disappointed the crowd of curious and unsupportive spectators waiting there, hoping to catch a glimpse of the conspicuous couple.

The complicated nature of Oregon’s anti-miscegenation laws had much in common with those of other states in the West—rather than focusing on white and Black relationships as did the South, legislators in the West beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century tended to include an array of racial groups in their bans. The increasing complexity of western marriage bans reflected the white lawmakers’ anxieties about the people they encountered in the region. Generally, laws in the West included Native Americans first, followed by the Chinese, and next by the Japanese, who were later to immigrate.

The editorialist’s scathing remarks illustrate the attitudes against such marriages held by some Oregonians at the turn of the twentieth century, including assumptions about the expected “disadvantages” of resulting offspring. Further, with the controversy over the meaning of “Mongolian,” the Aoki-Emery marriage “spectacle” highlights how racial categorizations change over time, often in response to social and political influences.

Further Reading:

Pascoe, Peggy. “Race, Gender, and Intercultural Relations: The Case of Interracial Marriage.” Frontiers 12, 1991: 5-18.

Smith, Matthew Aeldun and Charles Smith. “Wedding Bands and Marriage Bans: A History of Oregon’s Racial Intermarriage Statues and the Impact on Indian Interracial Nuptials.” M.A. Thesis, Portland State University: 1997.

Written by Sara Paulson, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.