- Catalog No. —

- Oregon Real Estate News, February 1956

- Date —

- February 1956

- Era —

- 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II), 1950-1980 (New Economy, Civil Rights, and Environmentalism)

- Themes —

- Black History, Government, Law, and Politics, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- National Association of Real Estate Boards

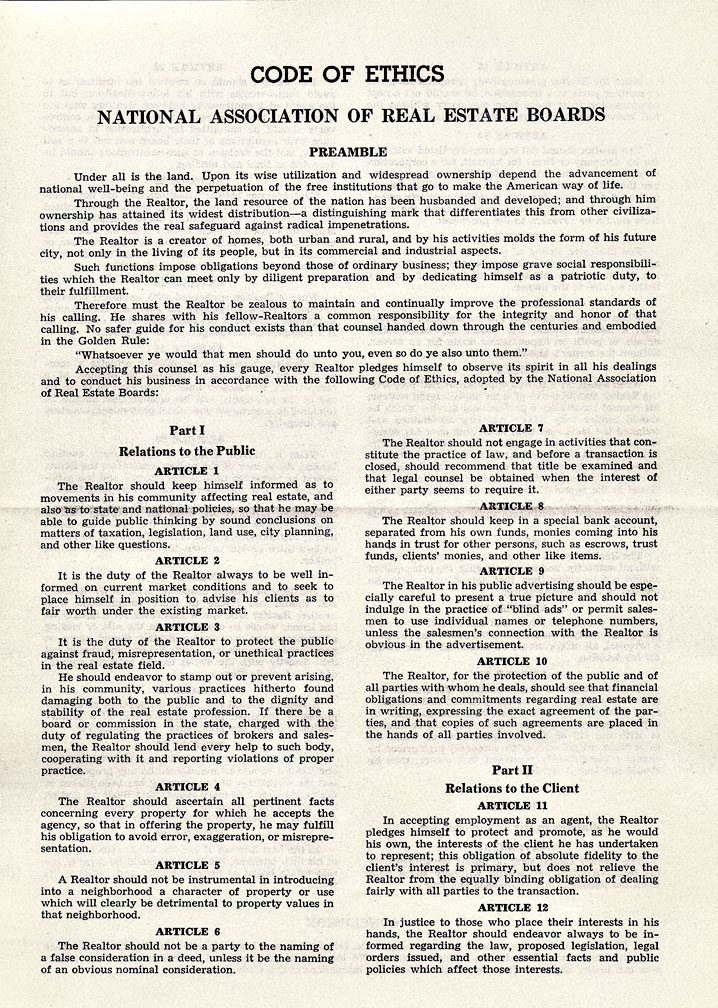

NAREB Code of Ethics

The Oregon Real Estate Department published this version of the National Association of Real Estate Board's (NAREB) code of ethics in its February, 1956 Oregon Real Estate News. The code was written to help guide realtor relations with the community, their clients, and fellow realtors.

In 1924, NAREB published its first code of ethics to guide realty agents in their daily business transactions in American communities. The code worked hand in glove with restrictive covenants which explicitly prohibited the sale or transfer of properties to specific racial, national, or religious group members to create a bulwark against non-white home ownership in all-white communities. According to article thirty-four of the 1924 code, “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”

In 1926 the U.S. Supreme Court determined the use of restrictive covenants to be legal in Corrigan v. Buckley. Subsequently, deeds restricting the transfer of property to non-whites and Jews became standard fare in white neighborhoods throughout the nation. Even the Federal Housing Authority made some of their housing assistance contingent upon restrictive covenants ostensibly to preserve the character and property values of existing neighborhoods. In many cities, like Portland, the use of restrictive covenants proved to be an effective means at keeping American communities segregated. However, a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court ruling (Shelly v. Kraemer) found deed restrictions unenforceable making residential segregation more difficult to maintain through the actions of home owners, buyers, real estate agents, and mortgage lending companies.

In 1950, NAREB responded to Shelly v. Kraemer by revising its code of ethics. In the code published by the Oregon Real Estate Board in 1956, explicit reference to race has been removed, replaced by the veiled discriminatory language of Article Five: “A Realtor should not be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or use which will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” Although NAREB boasted the change to be a “milestone” in the real estate industry’s relations with minorities, it was no secret that the rewritten code still referred to people of color, since their introduction into all-white neighborhoods was commonly believed to lower property values.

Although restrictive covenants were no longer legally enforceable after 1948, they were still one of the tools used by realtors to maintain segregated neighborhoods. In Portland, for example, when the flood of 1948 destroyed the Vanport community, many African Americans attempted to find homes in and around Portland’s metropolitan area. Most realtors responded by refusing to represent non-white clients, missing and canceling appointments with “colored” clientele, temporarily taking homes off of the market until they found white buyers, and making sales dependent upon the approval of white neighbors. Mortgage lenders typically refused to offer them credit. Most African Americans committed to remaining in Portland were left with little choice but to live in Albina, the city’s remaining neighborhood with a sizable African American population.

Further Reading:

Helper, Rose. Racial Policies and Practices of Real Estate Brokers. Minneapolis, Minn., 1969.

Writen by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.

Related Historical Records

-

Fair Housing in Oregon Study

This case study was included as an appendix by the League of Women Voters of Portland in A Study of Awareness of the Oregon Fair Housing Law and a …

-

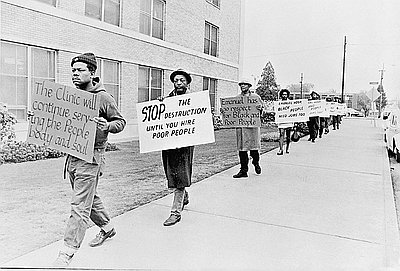

Albina Residents Picket the Portland Development Commission, 1973

Beginning in the 1960s, the City of Portland, with the cooperation of the Portland Development Commission (PDC) and Emanuel Hospital, began to lay the groundwork for redeveloping the …