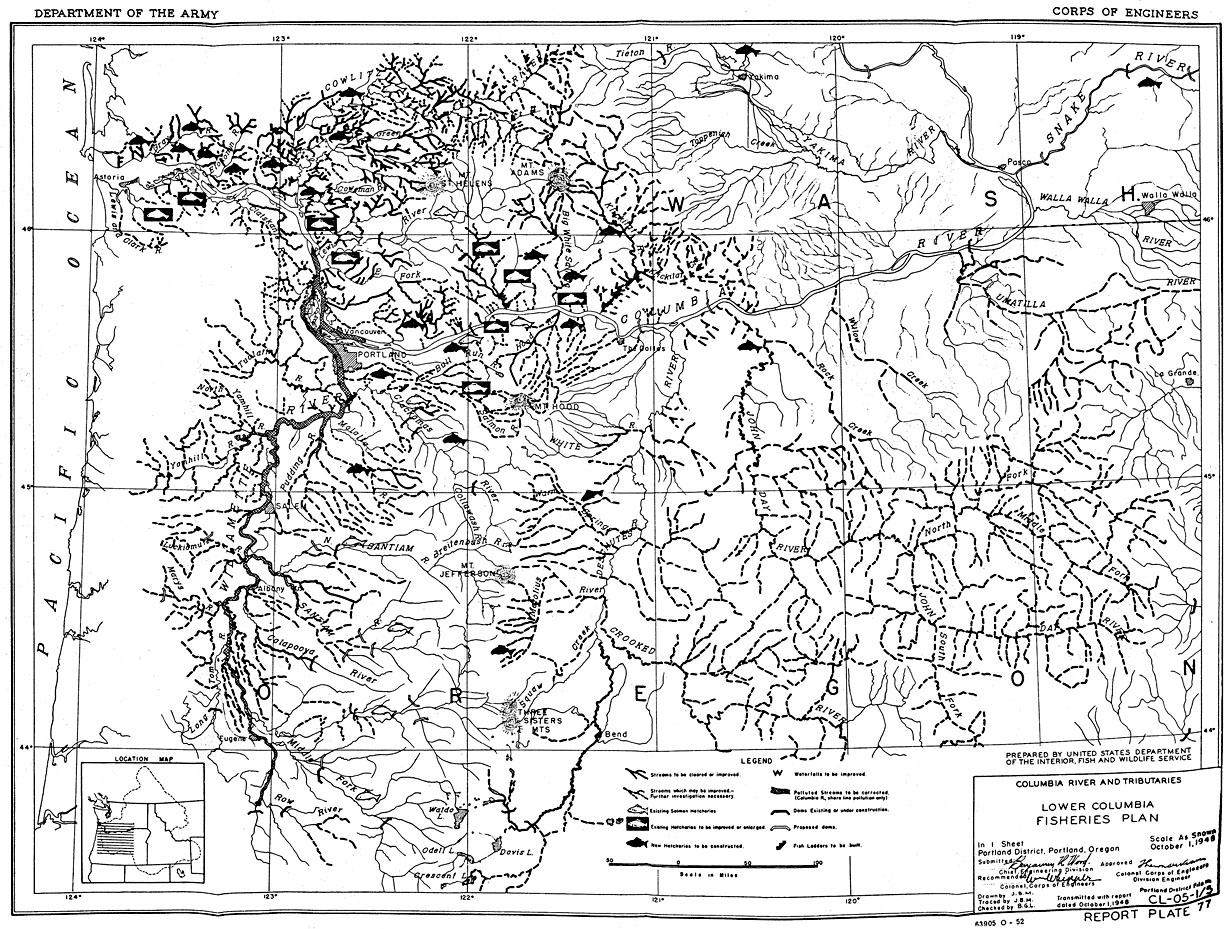

In 1949, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers included this map as a representation of the Lower Columbia River Fisheries Development Program in a “review of reports on, and preliminary examinations and surveys of, the Columbia River and tributaries” sent to Congress. In 1951, the Committee on Public Works ordered it to be printed as part of House Document No. 531. In 1956, the name of the plan was shortened to Columbia River Fisheries Development Program (CRFDP).

During the twentieth century, efforts to maximize the conservation of water for human uses led to the construction of an extensive array of dams in the Columbia River and its tributaries. The Army Corps and Bureau of Reclamation, responsible for building most of the big dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers, was warned by state and federal fishery agencies that the cumulative effects of federal dam construction had the potential to destroy salmon populations in the Columbia River Basin. Subsequently, in 1946, Congress authorized the CRFDP to mitigate damages to salmon that were likely to occur as more dams were built.

The CRFDP led to the construction and/or expansion of twenty-six hatcheries that propagated salmon and steelhead from eggs salvaged primarily upriver from the McNary Dam (1956). By relocating salmon to the lower portion of the river basin, fisheries managers hoped to save them from extinction while also propagating enough fish to support a commercial fishery. At the same time, the CRFDP led to the construction of forty-five formal fishways to allow for passage around smaller dams and irrigation works in the tributaries below McNary Dam. CRFDP funds also paid for the screening of irrigation ditches, the clearing of woody debris from streams—later learned to be detrimental to fish populations—and other habitat enhancement schemes. Unfortunately, because most of the work carried out under the CRFDP benefited the commercial fishery below the Bonneville Dam, Indian fishers, who were largely restricted to working the waters above Bonneville, were deprived of a proportionate share of federal assistance to sustain their fishery.

Undertaken as a last-ditch effort to salvage upriver salmon and steelhead populations, the success of the CRFDP was predicated on the creation of viable fish sanctuaries in the lower Columbia’s tributaries. However, during the 1960s, construction of two dams by the city of Tacoma on Washington’s Cowlitz River, along with the construction of three dams by Portland General Electric on Oregon’s Deschutes River, pre-empted the use of both rivers for fish propagation. The location of the John Day Dam on the Columbia just below the mouth of the John Day River also reduced the potential for propagation in that tributary as well.

Further Reading:

Allen, Cain. “Replacing Salmon: Columbia River Indian Fishing Rights and the Geography of Fisheries Mitigation.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 104, 2003: 196 – 227.

Taylor, Joseph E. Making Salmon: An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis. Seattle, Wash., 1999.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.