- Catalog No. —

- CN 008519

- Date —

- circa 1854

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration)

- Themes —

- Agriculture and Ranching, Arts, Exploration and Explorers, Oregon Trail and Resettlement, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Oregon Country Oregon Trail

- Author —

- Gustav Sohon

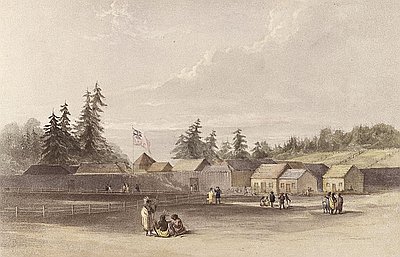

Lithograph of Fort Vancouver

This 1854 lithograph of Fort Vancouver was originally drawn by Gustavus Sohon while he and the U.S. Pacific Railroad Expedition and Survey team conducted a survey for railroad expansion from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

Prior to occupation by Euro Americans, the flat and mostly treeless plain — visible in the foreground — was used by Chinookan-speaking Indians, who gathered camas lily and wapato, nutritious roots found in wetlands. Klickitat Indians also frequented the area during their seasonal migrations, which took them from the Columbia River Gorge, near The Dalles, alongside Mt. Adams to present-day Vancouver. The Klickitat used fire to clear areas of dense forest along their trails, creating openings for the growth of edible and medicinal plants such as huckleberry, tarweed, and sunflower. The cleared plains made hunting easier because the grasslands attracted hungry deer and elk.

Impressed by the agricultural potential of the plains, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) relocated their headquarters from Fort George, present day Astoria, during the winter of 1824–1825, and by 1830 Fort Vancouver had become the first self-sustaining European settlement in the Pacific Northwest. As headquarters for the entire Columbia Department of the HBC, Fort Vancouver, under the leadership of men such as John McLoughlin and James Douglas, oversaw British fur trading operations from Alaska to Mexican California and from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. The HBC’s Fort Vancouver is shown at the middle right of image.

In the early 1840s large numbers of American settlers began arriving overland by way of the Oregon Trail. In 1846 the United States and Great Britain signed the Oregon Treaty, which officially divided the Pacific Northwest into British and U.S. territories at the 49th parallel, the present day United States-Canada border. HBC quickly relocated its headquarters to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, but kept Fort Vancouver operational until 1860.

The influx of land-hungry American settlers caused conflicts with the region’s Indian peoples. In 1849 the U.S. government responded to Oregon settlers’ calls for military assistance by stationing an army post at Fort Vancouver. Soldiers’ barracks were built on the hill directly above the HBC fort and an “officer’s row” of housing was built along the forest line. To this day, the post remains occupied by the U.S. Army.

When Gustavus Sohon made this drawing, HBC activities in Oregon Country had declined significantly. “Kanaka Village,” shown in the lower right of the drawing, was nearly abandoned, with only a few small houses still standing and inhabited. During the 1830s and early 1840s, the culturally diverse village community consisted of approximately 500 people. The village population was a mix of Hawaiians, Iroquois, Cree, French-Canadians, and dozens of local Native American groups.

Further Reading:

Boyd, Robert T. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline Among Northwest Coast Indians. Vancouver, B. C., 1999.

Gibson, James R. Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country, 1786 – 1846. Seattle, Wash., 1985.

Mackie, Richard. Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific, 1793 – 1843. Vancouver B. C., 1997.

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2003.

Related Historical Records

-

Drawing of Fort Vancouver

This hand-colored lithograph of Fort Vancouver was based on a sketch drawn by Henry James Warre in 1845 or 1846. The British government sent Warre, an army lieutenant, …

-

John McLoughlin to Hudson's Bay Co., 1828

John McLoughlin, chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia Department, wrote this letter to his superiors on August 10, 1828—two days after Arthur Black, one of four survivors of …