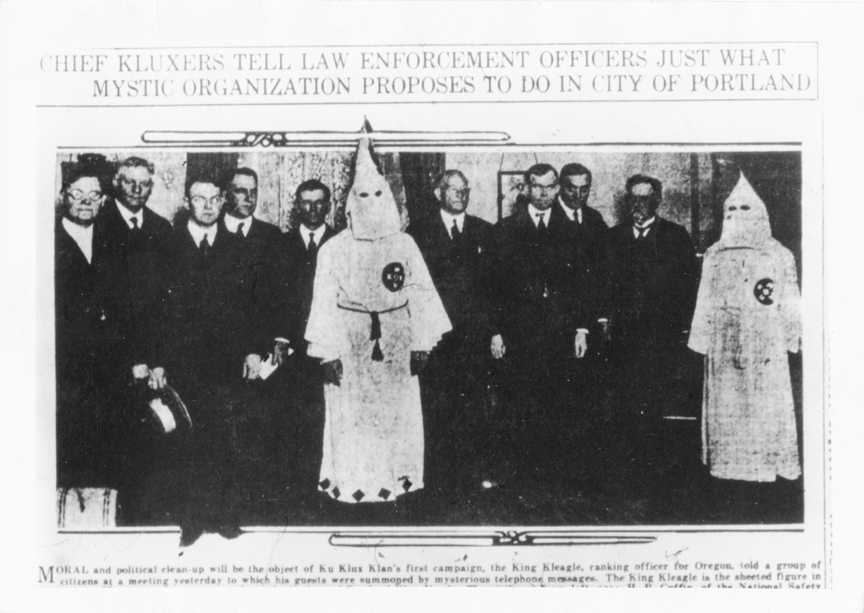

This photograph was published by the Portland Telegram on August 2, 1921, a day after reporters were summoned to the Multnomah Hotel in Portland by an enticing phone message. At the hotel (now Embassy Suites), the newspapermen entered a room crowded with some of the most influential men in the city, including the mayor and the chief of police, who had received the same phone call.

The calls had been made by members of the Ku Klux Klan, and at least two representatives of the Oregon chapter were there, dressed in the recognizable robes and hoods of Klan members. The Exalted Cyclops, standing on the right in the photograph, was Fred Gifford, a former line superintendent for the Northwestern Electric Company. Gifford had been named the chapter’s Grand Dragon in 1921 in an effort to recruit new members and gain influence in government. The "nameless officer" in the center of the photograph was King Kleagle, Luther I. Powell. He had called the meeting to counter the recent negative press against the KKK's activities and to document the supposed collaboration of Klan members and city officials in retaining "law and order."

The civic leaders posing with Powell and Gifford are, from left to right, H. P. Coffin of the National Safety Council; Captain of Police John T. Moore; Chief of Police L. V. Jenkins; District Attorney W. H. Evans; U.S. District Attorney Lester W. Humphreys; T. M. Hurlburt, a sheriff; Russell Bryon, a special agent of the U.S. Department of Justice; Mayor George L. Baker; and P. S. Malcolm, the sovereign inspector general in Oregon for the Scottish Rite Masonic Lodge.

The photograph indicates how comfortable KKK leaders were in the public spotlight during the early 1920s and how indulged they were by many civic governments. That night, Powell announced, "There are some cases, of course, in which we will have to take everything in our hands. Some crimes are not punishable under existing laws, but the criminals should be punished." He did not elaborate, but the implication was that the Klan felt entitled to act outside the law. In a room full of enforcers of the law, the two Klan members spoke freely, without fear of prosecution.

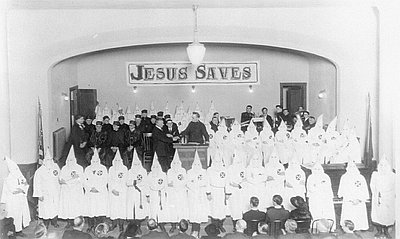

Klan membership in Oregon grew beginning in 1921, with chapters established throughout the state. Its popularity stemmed, in part, from a general racism against minorities (particularly Chinese and Japanese) and anti-Catholicism. During his term as Grand Dragon, for example, Gifford successfully lobbied for anti-Catholic legislation in Oregon. The political effectiveness of KKK chapters was due in large part to the relationships its leaders formed with Oregon policy makers, law enforcers, and fraternal organizations.

Mayor Baker remained close enough to Gifford to join Governor W. M. Pierce in honoring the Grand Dragon at a "patriotic dinner" in 1923. The KKK had endorsed Pierce in his 1922 campaign for governor, and his success indicated to members that Oregon chapters of the organization had some political legitimacy. The anti-Catholic and anti-minority laws passed by the Oregon legislature at the time broadly reflected the political and social attitudes of Oregonians in general, and it is likely that the KKK benefited from that environment rather than acting as its main architect. Cities such as Portland tolerated the Klan's initiation ceremonies and often turned a blind eye to burning crosses on Mount Scott and Mount Tabor.

Still, some Oregonians resisted. In Eugene, for example, an August 7, 1921, editorial in the Morning Register mocked the KKK and its parades on city streets: “There is a reasonable sprinkling of citizens who are pleasantly intrigued by the prospect of getting out in their nightshirts with their heads swathed in pillow slips with holes burned in them, and capering throughout the dewy night in pursuance of some ghostly ritual or other.” Judges and district attorneys across the country denounced the illegal acts of Klan members. And in the same Telegram article that described the Portland meeting, press releases on the community censure of Klan activity appeared, almost to refute Powell's assertion that "ninety-five percent of the stories are false."

By the middle of the 1920s, the KKK began to decline in Oregon, and most of the klaverns had dissolved completely by the end of the 1930s. By then, most people viewed the KKK as corrupt and had lost faith in its ability to solve social problems.

Written by Amy E. Platt, 2009; revised 2021

Further Reading

Horowitz, David. Inside the Klavern: The Secret History of a Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999.

Lay, Shawn. The Invisible Empire in the West: Toward a New Historical Appraisal of the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992.