- Catalog No. —

- Mss 1508

- Date —

- April 1, 1846

- Era —

- 1846-1880 (Treaties, Civil War, and Immigration), 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Transportation and Communication

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Central Northeast Oregon Trail

- Author —

- Stephen King & Mariah King

King Burial and a Letter

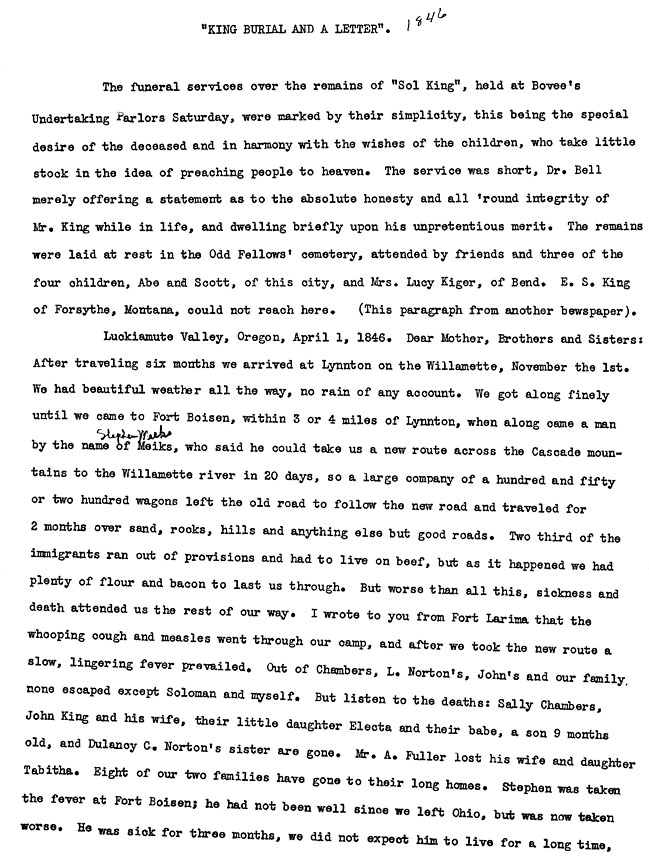

This manuscript consists of two separate documents that were copied by a researcher in 1925. The first is a description of funeral services for Solomon King, who died in 1913. The second is a letter written on April 1, 1846, by King’s brother and sister-in-law, Stephen and Mariah King. This letter contains an interesting description of the ill-fated Meek party, which attempted to find a shorter route to the Willamette Valley in the summer and fall of 1845.

The disastrous story of the “Lost Wagon Train of 1845,” as it came to be known, began in August 1845, when a massive wagon train consisting of over 1,000 people, nearly 200 wagons, and several thousand head of livestock arrived at old Fort Boise near present-day Parma, Idaho. The emigrants hired a mountain man by the name of Stephen Meek to guide them along what he claimed was a short-cut to the Willamette Valley. Meek assured the weary overlanders that his route would be 150 miles shorter than the old route, which headed northwest from Ft. Boise over the Blue Mountains. The emigrants’ decision to try the new route was encouraged by reports of Indian hostilities along the main road.

The wagon train rolled out of old Ft. Boise on August 23, heading west along the Malheur River. The road was good at first, with plenty of grass and water for the livestock, but it quickly turned dry and stony. On August 30, Samuel Parker, one of the leaders of the train, wrote in his journal: “Rock all day pore grass more swaring then you ever heard.” The train slowly made their way across the high desert, sometimes going days without water. On September 3, John Herren complained in his diary that Meek appeared to be lost and that “Some talk of stoning and others say hang him. I can not tell how this affair will terminate yet….”

Some of the exhausted emigrants began succumbing to disease, including whooping cough, measles, consumption, and what the Kings described as “a slow, lingering fever.” After six weeks of hard travel across the desert and over several mountain ranges, the wagon train finally arrived at The Dalles, though Meeks had fled several days before, apparently fearing for his life. The Kings estimate in the letter reproduced here that “upwards of fifty died on the new route.”

The Meek Cutoff was one of the greatest disasters to befall emigrants in the history of the Oregon Trail, and Meek’s name would be cursed for years afterwards. Nevertheless, the search for a cutoff across the high desert would persist for nearly two decades, though most overlanders would continue to follow the main emigrant road across the Blue Mountains.

Further Reading:

Boyd, Robert G. Wandering Wagons: Meek’s Lost Emigrants of 1845. Bend, Oreg. 1993.

Clark, Keith, and Lowell Tiller. Terrible Trail: The Meek Cutoff, 1845. Caldwell, Idaho, 1966.

Menefee, Leah Collins, and Lowell Tiller. “Cutoff Fever.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 77, 1976: 308-340.

Written by Cain Allen © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.