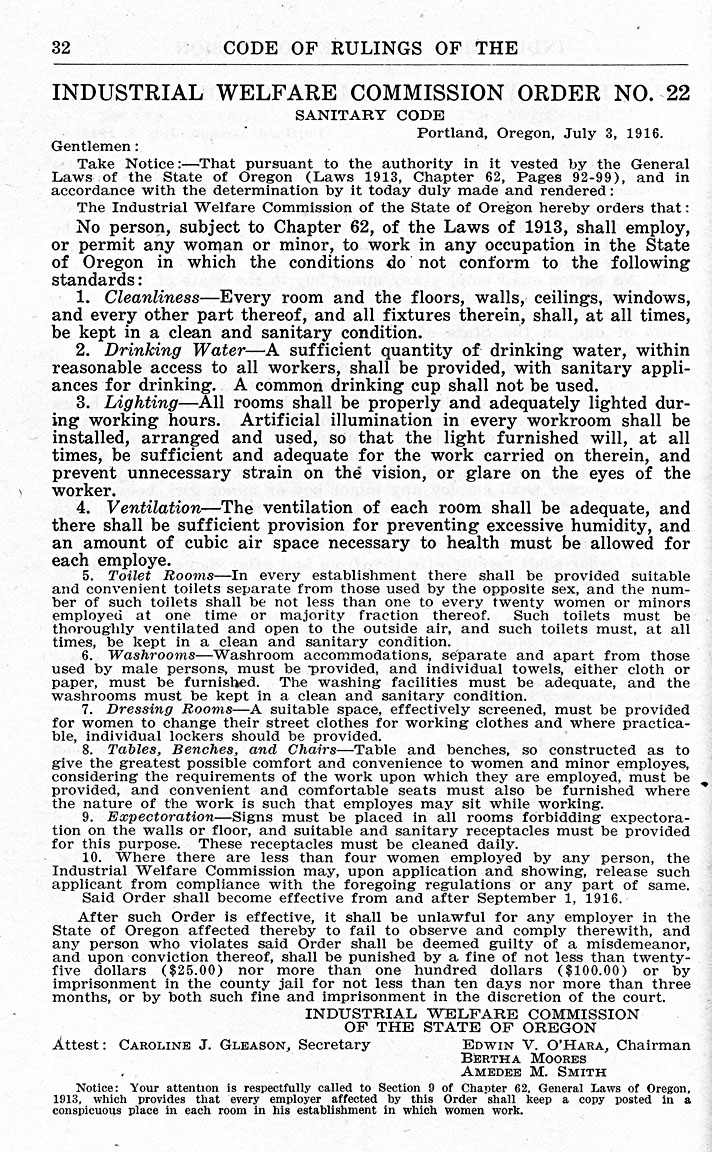

This order by the Oregon Industrial Welfare Commission established a sanitary code for workplaces with female employees. The order regulated lighting, ventilation, bathroom and changing room access, and required employers to provide women with places to sit during breaks. It even contained a restriction against “expectoration,” or the spitting of phlegm, on the floors or walls. Commission Chairman Edwin V. O’Hara printed the 1916 orders in a pamphlet entitled, A Living Wage by Legislation: The Oregon Experience, in which he recounted the successes of the minimum wage movement in Oregon, the nation, and abroad.

When the state legislature enacted a minimum wage law in 1913, it created the Oregon Industrial Welfare Commission to set occupational minimum wages, establish limits on working hours, and address sanitary regulations for female laborers. Three individuals comprised the Industrial Welfare Commission in 1916—one representative each for Oregon’s employers, female employees, and the public. Initially the commission called informal meetings with employers, hoping the business owners might volunteer acceptable figures with which to establish a minimum wage. When that strategy proved unsuccessful, the commission called employers together by industry in formal conferences and conducted public hearings. By the end of 1913, the commission created compulsory orders for employers to follow.

The minimum wage determinations included in the orders were the first in the nation to be adopted by a state commission. Massachusetts had similar legislation; however, without a commission to enforce it, the Massachusetts law required voluntary compliance by employers. Six other states followed Oregon in establishing minimum wage laws for women.

The commission established minimum weekly wages that ranged from $8.25 in smaller towns to $9.25 in certain occupations in Portland. Nine hours of labor was a common daily limit, fifty-four a common weekly limit. Other provisions of the code prohibited night work and established a forty-five minute lunch period.

Even following revisions in 1916, for no occupation did the commission’s minimum wage orders reach the figure the Consumers’ League of Oregon had suggested three years earlier in their Social Welfare Survey. The survey, which helped to convince Oregon legislators to establish the law, stated that women required at least ten dollars a week to live healthfully. Despite shortcomings, the Industrial Welfare Commission successfully raised wages in all occupations that employed women and forced employers to become more responsible about intolerable working conditions.

Further Reading:

Dilg, Janice. “ ‘By Proceeding in an Orderly and Lawful Manner’: Protective Legislation, Working Women, and Progressive Politics, 1913-1924.” Master’s thesis, Portland State University, 2005.

Written by Sara Paulson, © Oregon Historical Society, 2007.