- Catalog No. —

- Mss 1089

- Date —

- December 21, 1903

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Black History, Environment and Natural Resources, Exploration and Explorers, Native Americans, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society, Eva Emery Dye Papers

- Regions —

- Oregon Country

- Author —

- John T. Dizney

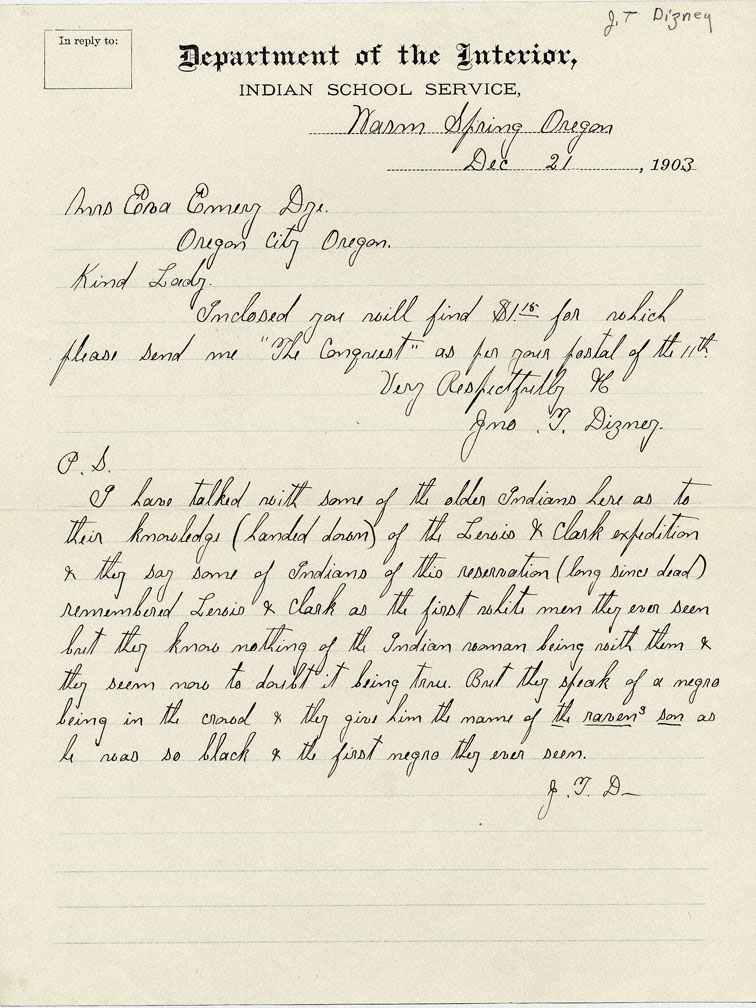

From J.T. Dizney to Eva Emery Dye

This letter was written in 1903 by John T. Dizney, an employee of the Warm Springs Indian agency, to Eva Emery Dye, an Oregon City-based novelist. It contains information about the Warm Springs Indians’ memory of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Dizney notes that while the Warm Springs Indians had no recollection of “the Indian woman” (Sacagawea), they clearly remembered York, who they named “the raven’s son.”

York, Captain William Clark’s slave and the only Black member of the Expedition, made a strong impression on many of the Native peoples the explorers encountered as they made their way across western North America. His presence helped ease diplomatic relations with a number of Native groups, most of whom had never seen a person of African descent.

Clark describes the reaction of the Arikaras, a northern Plains group, to York on October 20, 1804: “Those Indians wer much astonished at my Servent, they never saw Black man before, all flocked around him & examined. him from top to toe.” Sergeant John Ordway noted that the Arikara “children would follow after him,& if he turned towards them they would run & hollow [holler] as if they were terreyfied,& afraid of him.” York had great fun playing with the Arikara children, pretending to be a wild man only recently tamed. However, Clark, hoping to establish an alliance with the Arikaras and not wanting to risk alienating them in any way, quickly put a stop to York’s joke when he “made himself more turibal [terrible] than we wished him to doe.”

The Nez Perce of present-day Idaho were also fascinated by York. A 1903 letter to Eva Emery Dye, for example, has a brief reference to a group of Nez Perce women on the North Fork of the Clearwater River washing York’s skin to see if he was painted black. The letter writer noted that “the indians still tell of those things and show the places where they happened,” suggesting that York made quite a lasting impression.

Further Reading:

Millner, Darrell M. “York of the Corps of Discovery: Interpretations of York’s Character and His Role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 104, 2003: 302-333.

Betts, Robert B. In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis & Clark. Boulder, Colo., 2000.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Related Historical Records

-

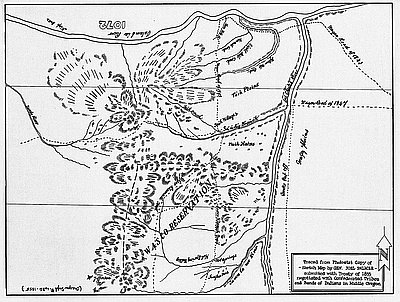

Wasco (Warm Springs) Reservation Map, 1855

From 1854 to 1855, Joel Palmer, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, negotiated nine treaties between Pacific Northwest Indians and the U.S. government. Many Indians agreed to …

-

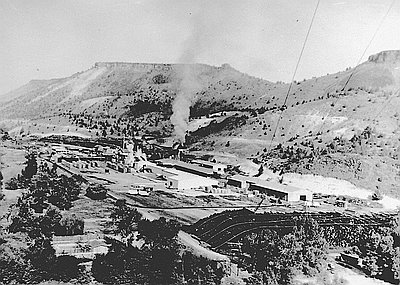

Warm Springs Reservation Mill

In 1938, four years after the congressional passage of the Indian Reorganization Act, the Warm Springs tribes became officially incorporated as the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs …

-

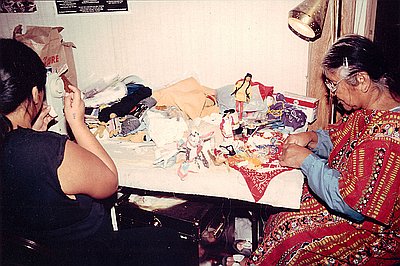

Traditional Warm Springs/Wasco Dollmaking

This photograph was taken in 1991 to document the work of Mary Ann Meanus (on right) as she trained apprentice Rhonda Arthur (on left) in the art of …