- Catalog No. —

- Oregonian, September 21, 1931

- Date —

- September 21, 1931

- Era —

- 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II)

- Themes —

- Government, Law, and Politics, Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- None

- Author —

- Ernesto A. Mangaoang, The Oregonian

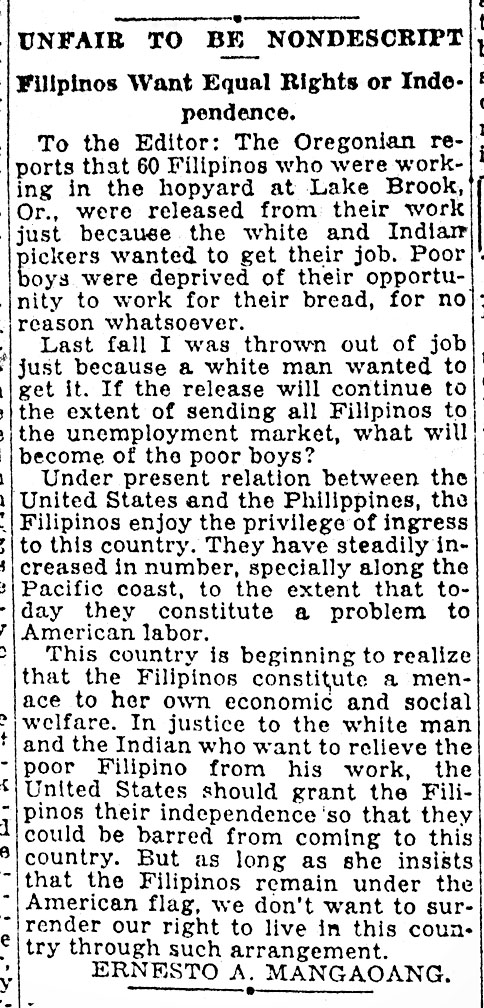

Filipinos Want Equal Rights or Independence

This letter by Filipino worker Ernesto A. Mangaoang was published in the Oregonian on September 21, 1931. Mangaoang describes the discrimination that Filipinos faced in Oregon during the Depression years. He concludes with a call for the independence of the Philippines.

When the Philippines became an American colony after the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), Filipinos were classified as U.S. nationals, allowing them to migrate to the United States in large numbers at a time when other Asians were excluded by discriminatory immigration laws. In 1910, there were only 406 Filipinos in the United States outside of Hawai’i. By 1930, this number had grown to 45,208, of which 1,066 lived in Oregon, 3,480 in Washington, and 30,470 in California.

Filipino immigrants soon became the focus of resentment among white workers in the western states, particularly after the onset of the Depression in the late 1920s. In the letter reproduced here, Mangaoang recounts how in the summer of 1931 dozens of Filipino hop-pickers in the Willamette Valley were fired “because the white and Indian pickers wanted to get their job,” and how he himself had been “thrown out of a job” the previous year because a white man wanted it.

Filipinos were also discriminated against in other ways. They were not allowed to own land in the state of Oregon, nor could they become naturalized American citizens. They also faced daily discrimination in commercial establishments. Portland’s Broadway Theater, for example, segregated Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese, and Blacks on the balcony; only whites were allowed on the first floor.

Mangaoang concludes the letter by calling for the independence of the Philippines, but remarks that as long as the United States “insists that the Filipinos remain under the American flag, we don’t want to surrender our right to live in this country.” In 1934, the U.S. Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which granted self-governing commonwealth status to the Philippines in preparation for independence ten years later. Like Mangaoang, many Filipinos supported independence even if it meant the end of Filipino immigration and the reclassification of Filipino workers in the United States as aliens. The Philippines achieved independence in 1946, though the U.S. continued to maintain a strong influence on the country’s economy and political system.

Further Reading:

Bulosan, Carlos. America is in the Heart. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973.

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. New York: Penguin Books, 1989.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004