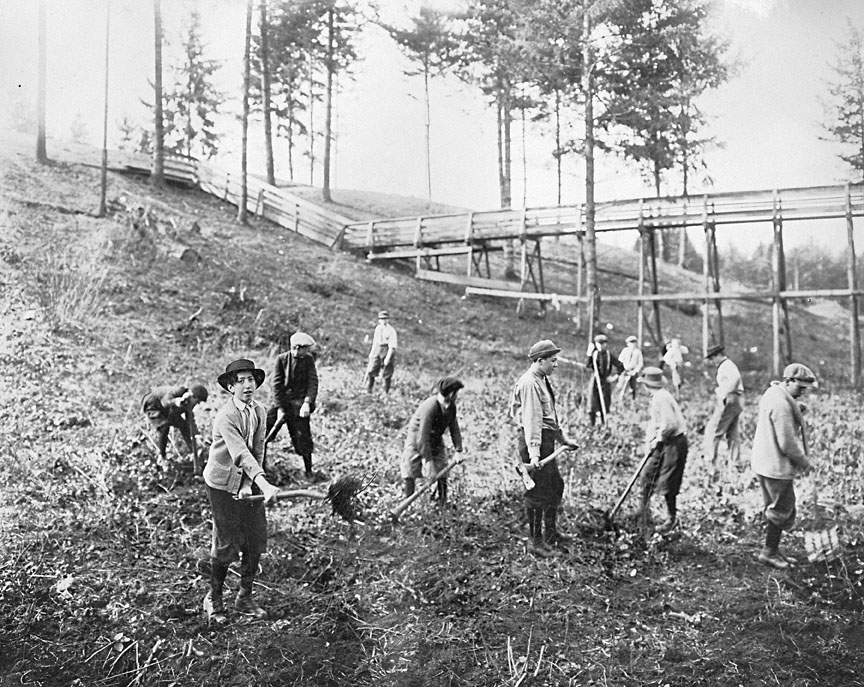

This photograph belongs to a collection that documented the Portland Public School’s garden contest in 1914. The boys depicted in it were Portland’s Creston primary school students. They were preparing the soil for the school’s garden.

Creston gained city-wide attention in 1914 due to a controversy that raged between parents and municipal health officials about mandatory smallpox vaccinations in public schools. While all agreed that smallpox was dangerous and potentially deadly, many argued that compulsory vaccinations limited the individual’s right to address the health needs of one’s own family. Although the success rate of vaccinations had improved significantly by the turn of the twentieth century, the procedure was not fool-proof. Vaccinations could lead to infections—sometimes deadly ones. Across the United States groups of skeptics resisted the paternalism of medical experts.

In 1914, city and state laws granted Portland’s municipal health officials the power to keep unvaccinated children home from school for two weeks during smallpox outbreaks. When a number of children in the southeastern part of the city contracted the disease, City Health Officer M.B. Marcellus mandated that all students of Creston, Arleta, Woodmere, and Hoffman primary schools and Franklin High School receive vaccinations or stay home. Parents effectively shut down the five schools by opting for the second choice.

At a city commission meeting and assemblies of their own, angry parents rallied to force Marcellus to readmit their children without vaccinations. One Creston parent took the issue to court, resulting in a temporary injunction preventing school officials from keeping the children out of class.

The issue came alive again in 1916 and 1920, with two citizen-led initiatives aimed at banning compulsory vaccination. Again, neighborhoods near Creston were some of the most outspoken. While the measure nearly passed in 1916, the matter showed signs of decline by 1920. After its second failure, compulsory vaccination never again appeared on the ballot, perhaps signaling a growing trust of the medical profession. Nevertheless, the short-lived resistance is an example of a social struggle between some members of the middle class and their government. Historian Robert D. Johnston put it well when he suggested that the struggle was as much over “public application and power of expertise as over pus and pox.”

Further Reading:

Johnston, Robert D. The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon. Princeton, N.J., 2003.

Written by Sara Paulson, © Oregon Historical Society, 2006.