- Catalog No. —

- OrHi 104921

- Date —

- 1841

- Era —

- 1792-1845 (Early Exploration, Fur Trade, Missionaries, and Settlement), Oregon Country before 1792

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Exploration and Explorers, Native Americans

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River Willamette Basin

- Author —

- Alfred T. Agate

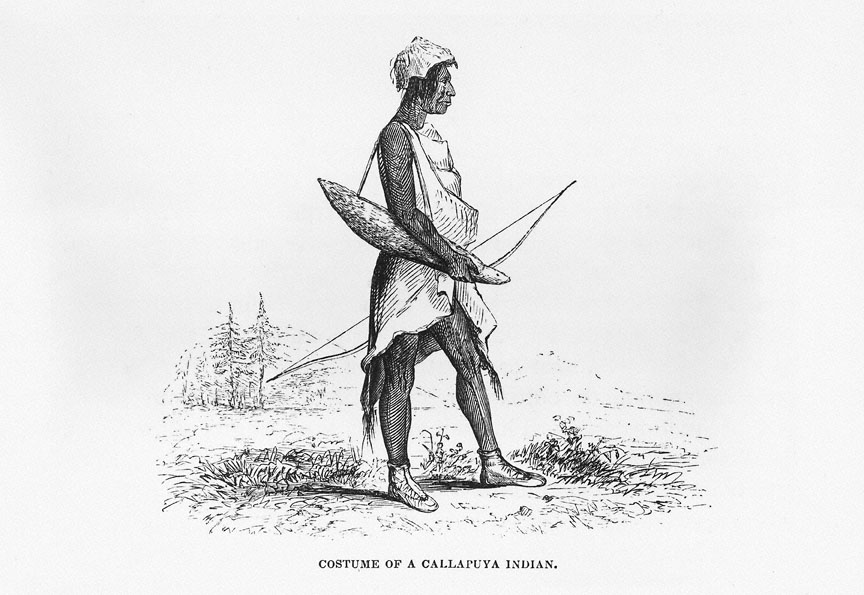

Costume of a Callapuya Indian

This engraving from a sketch by artist Alfred T. Agate depicts a Kalapuyan man dressed in pre-contact fashion, carrying a bow and what appears to be an animal skin quiver to hold his arrows. Agate made the sketch as a member of the Wilkes Expediton in their overland travels from the Columbia River to San Francisco in 1841.

Prior to the arrival of Euro American explorers and traders in the late 1700s, the inland valleys between the Coast range and the Cascades were home to a number of ethnically-related native groups collectively known as Kalapuyans. There were three major ethno-linguistic divisions of these inland groups. In the north were the Tualatin-Yamhill whose territory to the west of the Willamette River extended from Willamette Falls south to the central Willamette Valley. A large grouping of 10-15 related bands occupied primarily the central and southern portions of the Willamette Valley, while the Yoncalla inhabited the uppermost reaches of the Umpqua Valley. The Kalapuyans are notable among the Oregon Indians for a unique lifestyle that melded elements from both coastal and plateau cultures. Between spring and summer they lived a semi-nomadic existence, roaming the inland river valleys of Oregon in pursuit of seasonally available plants and animals for sustenance. In winter, they passed the rainy season in permanent, multi-family lodges.

When Euro Americans began to settle the Willamette Valley in the 1830s, they faced an unusual situation. Unlike settlers in most other parts of the Pacific Northwest, they experienced almost no resistance by Native peoples. The Kalapuyans had earlier been decimated by a series of epidemics that started with a smallpox outbreak in the early 1780s and culminated with a particularly lethal epidemic of what is thought to have been malaria. The malaria epidemic struck the Lower Columbia and Willamette regions between 1830 and 1833. By 1844, only about 300 Kalapuyans remained of the estimated 13,500 that had inhabited the Willamette and Umpqua Valleys at the time of European contact. This last epidemic of “fever and ague” so completely devastated the Kalapuyans that they had neither the means nor the strength to resist Euro American settlement. Those who did survive were moved onto an increasingly shrinking series of reservations; in 1856 they ceded 7.5 million acres of their lands to the U.S. government for $200,000.

Given the small number of survivors, it is often assumed that the Kalapuyans are extinct, a misconception that was reinforced by early twentieth-century newspaper accounts that heralded the death of the “Last of the Kalapuyans.” Following their removal to the Grand Ronde and Siletz reservations, the remaining Kalapuyans intermarried with other tribes. The descendants of these intertribal marriages ensure that the Kalpuyan lineage survives to this day.

Further Reading:

MacKey, Harold. The Kalapuyans: A Sourcebook on the Indians of the Willamette Valley. Salem, Ore.: 1974.

Boag, Peter G. Environment and Experience: Settlement Culture in Nineteenth-Century Oregon. Berkeley, Calif.: 1992.

Boyd, Robert T. “Another Look at the ‘Fever and Ague’ of Western Oregon.” Ethnohistory, 22 1975: 135-154.

Written by Melinda Jette, Joshua Binus © Oregon Historical Society, 2004