- Catalog No. —

- U.S. House Doc 531

- Date —

- 1948

- Era —

- 1921-1949 (Great Depression and World War II)

- Themes —

- Environment and Natural Resources, Government, Law, and Politics, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River

- Author —

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

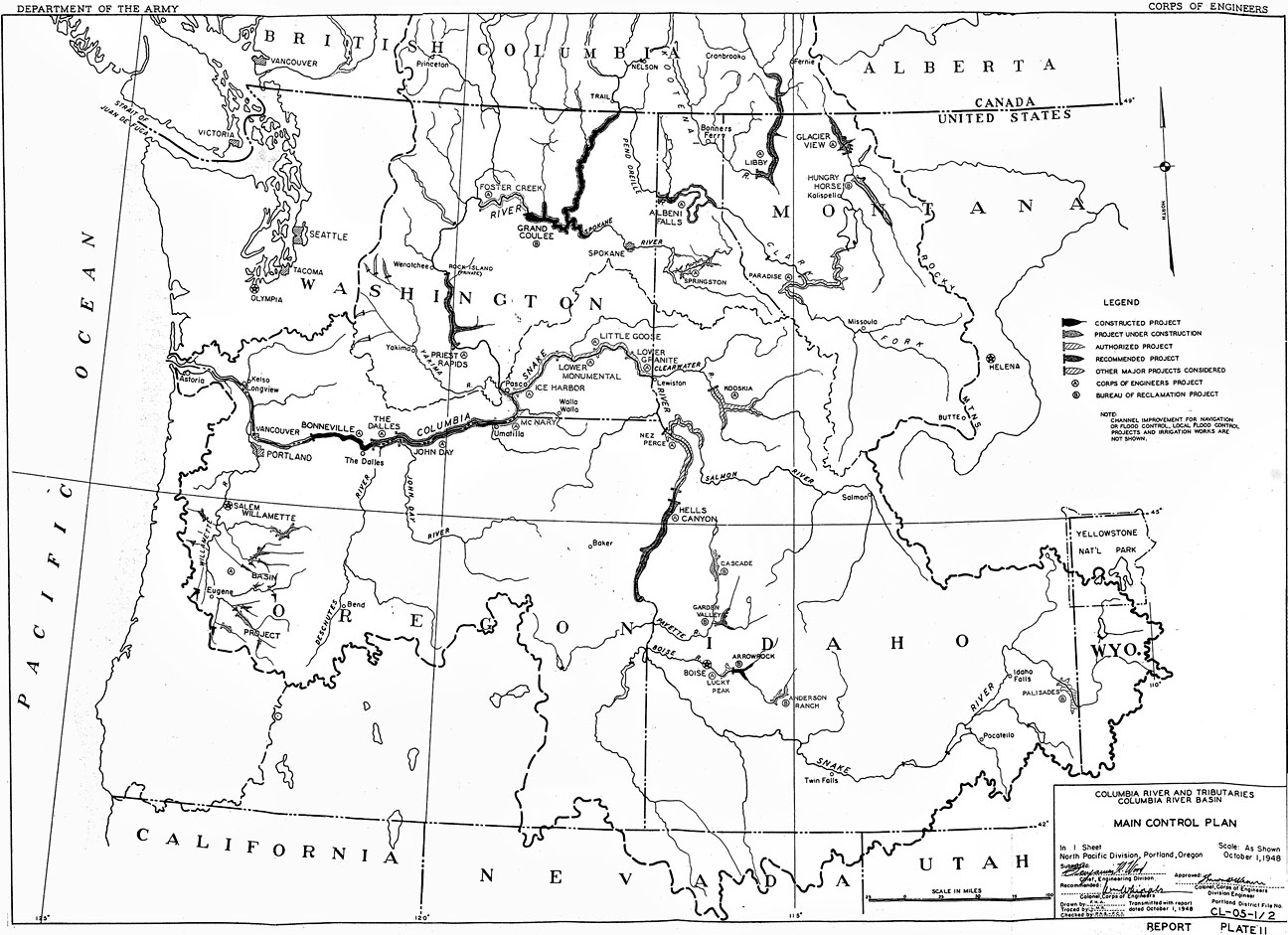

Columbia Basin Main Control Plan

In 1949, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers included this map of their Main Control Plan in a “review of reports on, and preliminary examinations and surveys of, the Columbia River and tributaries” sent to Congress. In 1951, the Committee on Public Works ordered it to be printed as part of House Document No. 531. The Main Control Plan represents the evolution of the Army Corps’ strategy to develop a series of multiple-purpose dams designed to store flood water, allow for commercial river transportation, provide water for irrigation projects, and produce electricity.

Proponents of the Main Control Plan considered the conservation of Columbia River water to be one of the most pressing needs in the Northwest. Every summer, as they saw it, a wealth of water was “wasted” from the Columbia River system, allowed to flow unimpeded from the mountains to the ocean without first being put to beneficial use. The annual rush of summer snowmelt inundated communities living along floodplains, and the low-water-levels during the winter months regularly impeded river travel. The dams proposed in the Main Control Plan promised to alleviate the worst of the flooding and provide year-round river transportation as far upriver as Pasco, Washington and Lewiston, Idaho. The water impounded in the dams’ reservoirs—especially behind the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington—was hailed as a means to “make the deserts bloom” with commercial crops and thriving communities. Finally, the hydro-electric power produced by the dams promised to provide the quickly growing cities and towns of the Pacific Northwest with ample energy to meet their needs. The federal government hoped to pay for the astronomical costs of the plan by selling electricity from each of the dams, making them “self-liquidating.”

Less enthused about the dams were those people whose livelihoods and communities were dependent upon free-flowing rivers, most notably—but not exclusively—by those people whose lives were tied to salmon fishing. Indian communities throughout the Columbia River Basin found themselves almost wholly excluded from the planning process, their concerns addressed by the Army Corps and Bureau of Reclamation only as an afterthought. Non-Indian commercial and sport fishers similarly found their lifestyles and occupations threatened. However, the Army Corps took some steps to accommodate the latter’s concerns early on, primarily by designing some dams with fish passage facilities and by constructing fish hatcheries along the lower Columbia—below the waters fished by Native Americans. Even so, salmon populations—along with sturgeon, lamprey eel, and euchelon (smelts)—have declined precipitously as a result of the development of the dams called for by the Main Control Plan.

Further Reading:

Lowitt, Richard. The New Deal and the West. Bloomington, Ind., 1984.

McKinley, Charles. Uncle Sam in the Pacific Northwest: Federal Management of Natural Resources in the Columbia River Valley. Berkeley, Calif., 1957

Written by Joshua Binus, © Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Related Historical Records

-

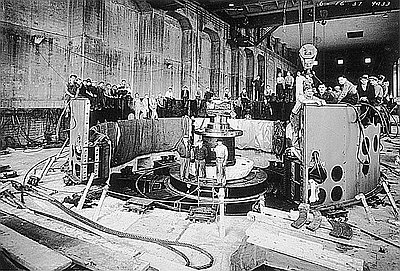

Bonneville Dam Workers Assembling Turbine

In 1937, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) completed construction of Bonneville Dam, located forty-two miles east of Portland on the Columbia River. The dam’s turbines, connected …

-

Workers at Bonneville Dam Site, 1935

This 1935 photograph shows workers excavating volcanic rock at the construction site of Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River. Workers used jackhammers and explosives to remove rock in …