- Catalog No. —

- OHS Museum Collections

- Date —

- 01/01/1811

- Era —

- 1792-1845 (Early Exploration, Fur Trade, Missionaries, and Settlement)

- Themes —

- Exploration and Explorers, Geography and Places, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Columbia River Northeast

- Author —

- Michael McKenzie

1811 Trailmarker

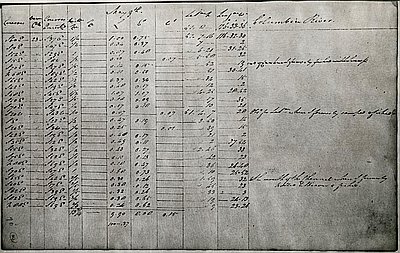

Sometime around the summer of 1944, ten-year-old Douglas Owen found the 120-pound basalt rock shown above near the town of Bates, located about thirty miles northeast of John Day. The rock, which is carved with a cross and the year “1811,” remained where it was until about 1956, when Owen and his father moved it to their home in Bates. The Owen family maintained possession of the unique artifact until 2003, when they donated it to the Oregon Historical Society.

The year 1811 saw the arrival of two land-based fur trading expeditions in the Oregon Country, an American expedition organized by New York financier John Jacob Astor, and a Canadian expedition led by geographer David Thompson. Thompson’s expedition stuck close to the Columbia River, but the Astorians explored large portions of the interior, including present-day eastern Oregon.

While heading westward towards the Columbia River, the Astorians split into five groups. Two of the fur traders, Ramsey Crooks and John Day, became separated from their party and wandered lost for months in the Blue Mountains. Until recently, historians thought that the two Astorians never reached the headwaters of the John Day River, but the presence of the inscribed rock suggests otherwise. After reviewing the historical record, historian Michael McKenzie concluded that “it seems probable that it was Ramsey Crooks who carved the date and cross on the rock, with John Day right there beside him.”

Crooks and Day eventually found their way to the Columbia River, but a local Indian group robbed the pair of all their possessions and left them naked near the mouth of the river that would later bear John Day’s name, apparently as revenge for the deaths of Indians at the hands of whites some months earlier. Crooks and Day were traumatized by their ordeal. Crooks left the Oregon Country at the first opportunity; he later became a successful trader, purchasing the American Fur Company from Astor. Day did not fare so well. In his 1836 book Astoria, novelist Washington Irving claimed that Day went insane and died around 1813. However, other evidence strongly suggests that Day survived until 1820, when he was probably killed by Indians in the Snake River country.

Further Reading:

Elliott, T.C. “Last Will and Testament of John Day.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 17, 1916: 373-379.

McKenzie, Michael. “Using Artifacts to Study the Past: Early Evidence for John Day Exploration.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 104, 2003: 578-595.

Written by Cain Allen, © Oregon Historical Society, 2005.