In 1848, two years after Lindsay Applegate traveled through the Rogue River Valley, the discovery of gold in Sutter’s Mill, California, brought prospectors through southwest Oregon. In 1850 and 1851, miners found gold on Josephine Creek, on the Illinois River, and on creeks near Jacksonville, Oregon. Publicity about the find in the San Francisco Alta California brought miners to the region from California and the Willamette Valley, and before long gold-seekers had staked claims on the Applegate, Illinois, and Rogue Rivers. Miners also worked placers on the coast near Pistol River and Port Orford and at present-day Gold Beach, where black sand held gold and platinum deposits.

The miners, primarily men in their twenties and thirties, came from countries that included Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland, Germany, and England, and states such as Massachusetts, New York, Missouri, and Tennessee. The 1860 federal census counted several hundred miners in various mining precincts. Using rockers and sluice boxes to process the gravels, enterprising miners worked long hours. “I commenced to dig,” Herman Reinhart wrote while working in the Waldo area. “After getting down about two or three feet, I washed out a pan of dirt and got a good prospect of coarse gold….We kept bailing out the water and digging down to about three and a half feet. It was so good a prospect that I concluded to stake off our claims.”

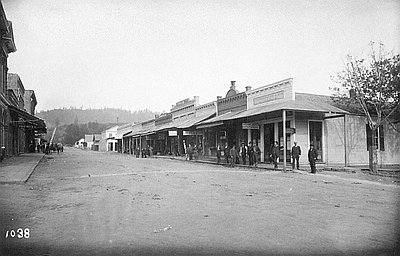

At Althouse, Browntown, and Sterlingville, canvas tents and log dwellings clustered near the diggings. The mining camps of Waldo and Ellensburg (Gold Beach) soon developed into service centers, and frame and brick buildings replaced temporary structures. Jacksonville emerged as the first true community in the region, with churches, schools, boarding houses, and saloons.

The initial boom of gold placer mining in southwestern Oregon ended by the late 1860s; and, with few exceptions, the mining camps disappeared from the landscape. As the miners moved on, merchants and farmers became the new leaders in the economy. Still, the miners left an altered landscape behind them—hillsides stripped of timber, vegetation hacked away to clear streambanks, and water diverted for mining ditches. Only late-nineteenth-century hydraulic miners would exceed this destruction.

Southwestern Oregon mining communities contained people from a number of different ethnic groups. The Chinese, most of them from Kwangtung (Gwangdong) Province, represented the largest single ethnic group in the region. According to the 1860 census, they made up at least 50 percent of the men identified as miners.

Working efficiently and satisfied with lower returns, the Chinese stood in sharp contrast to the white miners’ “get-rich-quick” ethic. Subject to suspicion and racism, Chinese miners gravitated to previously worked areas to rework ground that earlier miners had ignored. As long as gold remained relatively plentiful and accessible, white miners largely left the Chinese alone and occasionally sold claims to them, despite laws that prohibited Chinese from owning property. In 1865, a visitor to Waldo observed: “Chinamen are gradually supplanting the white miners in this section of the country….They are mostly working diggings that have been deserted, or sold to them by white men.”

As the easily obtainable gold disappeared, local attitudes toward the Chinese grew harsher. Jacksonville’s Oregon Sentinel editor wrote on September 1, 1866: “These people bring nothing with them to our shores, they add nothing to the permanent wealth of this country and so strong is their attachment to their own country they will not let their filthy carcasses lie in our soil.”

Through the 1870s, Chinese labored in southwest Oregon as laundry workers, packers, and cooks. When Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, many local Chinese left the region for larger cities, and others returned to China. Chinese residents who died in southwest Oregon lay in cemeteries in Waldo and Jacksonville until district associations, including the Chinese Six Companies of San Francisco, arrived to exhume the remains to return to home villages in China.

Despite relatively high numbers of Chinese residents during the peak mining years, the region’s population remained overwhelmingly Caucasian. Jackson County, the largest political subdivision in the region, had 4,778 residents in 1870, 634 of which were Chinese. In 1900, with a population of 13,698, the county had only 43 Chinese residents.

© Kay Atwood and Dennis J. Gray, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.