Written by Michael N. McGregor

One spring day in 1881, when Malheur Lake was filled with mountain runoff, some of its water spilled into nearby Harney Lake. Cowhand Martin Brenton claimed he started the spill by kicking at a reef of sand. Others said it began by itself when Malheur Lake overflowed. Whatever set it in motion, the spill worsened already tense relations between local settlers and cowmen, producing a series of bitter clashes that left one of the West's most-successful cattle barons dead.

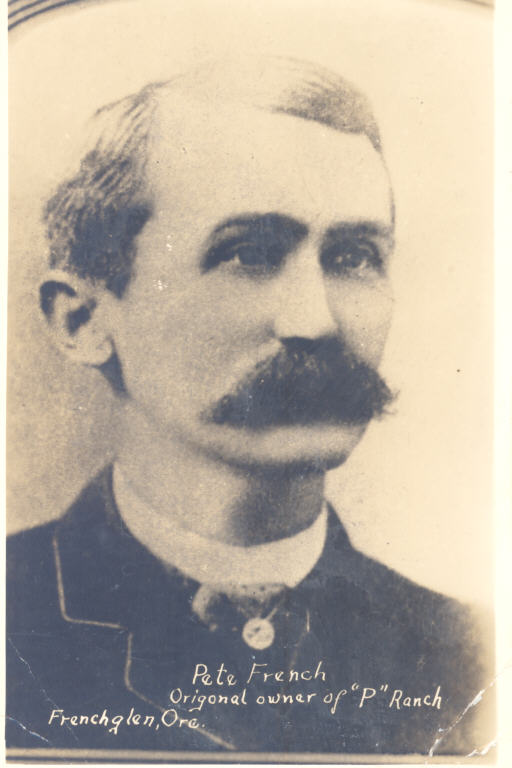

Malheur Lake lies in the dry southeast corner of Oregon. At the end of the 19th century, much of the land was controlled by powerful cattlemen such as Brenton's boss, Peter French. Though he stood only five-and-a-half-feet tall and weighed just 125 pounds, French had a huge reputation. His fame as a cattle baron extended far beyond Oregon, and his death at the hands of a settler stirred passions for years to come.

French moved to southeast Oregon in 1872 at the age of 23, taking along 1200 shorthorn cows. He was one of the first of the many cattlemen who headed north from California after the U.S. Army forced the Paiute and Bannock Indians of southeast Oregon onto reservations. Within a few years, cattle were everywhere in the southeast except high in the Steens Mountains and in the swamp land close to Malheur and Harney Lakes.

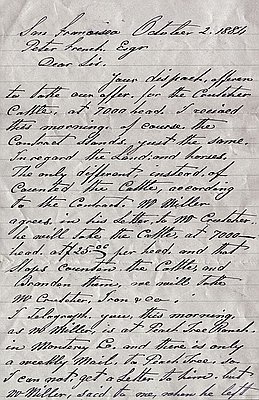

Backed financially by Dr. Hugh J. Glenn—a Californian nicknamed "The Wheat King" because he grew more wheat than anyone in the U.S.—French began buying up land as soon as he arrived in Oregon. By the mid-1880s, he had assembled a 70,000-acre spread with 45,000 head of cattle, making his the largest ranch around. In his best years, he grossed over $100,000 from cattle sales, an enviable sum in those days.

Not long after the cattlemen arrived in southeast Oregon, farmers began homesteading in the same area. At first, French and the homesteaders got along well. He occasionally bought land from them and when he did, he paid a fair price. Many admired him for the size of the operation he had put together. But as the 1880s wore on and more and more settlers arrived, French and the farmers found themselves increasingly at odds. By the early 1890s, they had long been battling each other in the courts, arguing primarily over rights to water and land.

French's ranch included the southern shoreline of Malheur Lake, where the 1881 spill occurred. The spill lowered the lake's depth by a foot or more, exposing 10,000 acres of previously unusable land. Settlers moved in to farm the land, as they had when diversions for irrigation had lowered water levels before. French didn't seem to mind at first. He hired some of the settlers to work for him and, according to Giles French in his book Cattle Country of Peter French, helped them in other ways, too—giving them beef, for example, if they didn't have enough food to make it through the winter.

Eventually, though, as more settlers arrived, French began to send the settlers eviction notices, claiming that Oregon law gave the owner of a lake's shoreline ownership of everything out to the middle of the lake. The settlers countered by claiming that the exposed ground was no longer part of the lake but new land that they had a right to homestead on. By 1895, the dispute had led to five major court cases. As the cases dragged on, dislike of French grew. Surrounded by hostile settlers, French became more and more isolated and withdrawn.

Among those French disliked most was a settler named Ed Oliver, who owned a small ranch in the middle of French's land. The dislike was mutual, though Oliver worked for French for a while. The two had the usual arguments over use of water and land. What angered French most was that Oliver had asked the courts for—and won—a right-of-way to drive his cattle across French's land. The bitterness between the two men grew until one day after in 1897,sixteen years after the Malheur Lake spill, it resulted in deadly violence.

The day after Christmas that year, during a roundup of local cattle, Oliver was crossing one of French's fields when French approached him. Accounts of what followed vary, but all seem to agree that French was angry. He was unarmed but Oliver may have felt threatened. When French turned away again, Oliver took out a pistol and shot him dead.

At the subsequent trial, Oliver's attorneys claimed self-defense, citing French's growing hostility toward the settlers around him and his previous violence. They portrayed Oliver as a model citizen. The jury acquitted him. A short time later, he disappeared, leaving behind his wife and children and taking the contributions the local community had donated to help his family during the trial.

French's death wasn't the only one to result from clashes between cattlemen and settlers in Oregon or elsewhere, but it became one of the most famous. Eventually, so many settlers came to even the most desolate areas that the great cattle barons disappeared. The free, open land the cattlemen had raised their herds on was parceled out and fenced off. And men like Peter French passed into legend.

Click here to read "Big Country: Where Pete French Was Killed," by Rankin Crow.

© Michael McGregor, 2004

Michael McGregor is Associate Professor of Non-fiction writing and English at Portland State University