Written by Michael N. McGregor

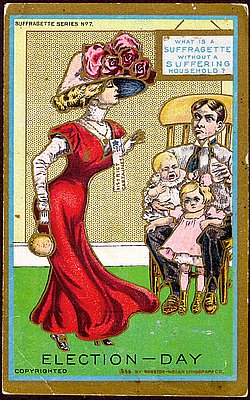

The colors clash. The fabrics jar. The garish designs are dizzying hexagons of mismatched stripes and solids, all placed awkwardly inside a hem of blooming onions. It is not so much a quilt as a parody of quilting. You can almost see the glee in Abigail Scott Duniway's face as she jabs her needle through the fabric, intending her handiwork to illustrate what she believes: that women should concern themselves with more important things—that "any fool can make a quilt."(1)

In 1900, when Abigail completed this one extant example of her "wifely" work, she was 66 years old. Thirty years had passed since she had first assembled it, intending it to mark the birth of her sixth child. During those 30 years, she had no time for quilting. She was busy journeying from frontier wife to leader of the struggle to bring legal rights to Northwest women. Her handiwork became securing women liberties they had never been allowed. Abigail's journey began long before her quilting stopped. As a child in the early 1800s, she saw frontier life weaken her mother and felt its harsh effects herself. In later years, she spoke with bitterness of churning butter, picking wool, and stringing apples endlessly for drying—all before the age of ten. The resodding of a blue grass lawn when she was nine, she said, gave her "a chronic weakness of the spine." (2)

This took place in Illinois, before her family moved west—before her father ordered her, at 17, to record each day's events along the Oregon Trail, including her mother's early death from cholera.

When the family reached Oregon, Abigail taught school for several months in Yamhill County before marrying Ben Duniway, a horseman living on a 320-acre claim. Soon a child was on its way. At 19, pregnant and isolated on a farm, it might have seemed her destiny was set. But Abigail Scott Duniway was never one to acquiesce to fate.

Emboldened by her anger at the hardship she had witnessed since her youth, empowered by her love of books, Abigail soon wrote a novel that depicts a frontier woman's life, complete with all its difficulties. Though the publication of Captain Gray's Company when she was 25 did not bring her renown, it gave her confidence in her own abilities. Down the road this confidence would change her life.

In the years ahead, Abigail did her best to work without complaint, raising her six children, churning butter, milking cows, and feeding the many bachelors her husband Ben brought home. But in 1861, she watched helplessly as Ben signed notes that made their farm the surety for another man's loan. As a woman, Abigail had no legal right to vote nor to contest the legal action of her husband. She was bound by what he signed. When the man defaulted on the loan, the farm was lost.

Homeless and without a source of income, the Duniways moved to Lafayette, Oregon, where Ben took a teamster job. One day the horses threw him in the path of a heavily loaded wagon that crippled him for life. Abigail had no choice but to return to work. She taught school in Lafayette, then opened a small school in Albany, eventually converting it into a millinery store, the only other line of work available to women. In this store, Abigail saw how widespread women's problems were and began her work for women's rights.

The hardships Abigail heard about stemmed primarily from women's lack of legal power. One woman begged for sewing work because her husband had spent the family's "butter money" (the income from her churning) on a racehorse. Another said her husband had sold the family's furniture and disappeared, leaving her without enough to feed her five small children. Neither woman had the right to take her case to court.

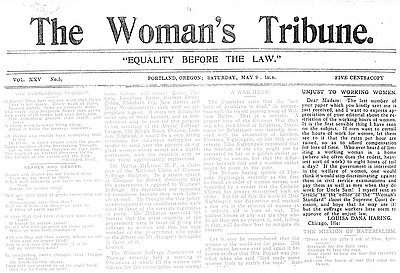

In 1870, having already allied herself with suffrage groups in Oregon, Abigail used a fabric-buying trip to San Francisco to meet a group of national suffrage figures gathering there. One year later, with her husband Ben's encouragement, she bought a printing press to start The New Northwest, a weekly newspaper. Over the next 16 years, she used the stories she had heard and her own experiences and thoughts to make her paper the Northwest's premier voice for women's rights.

In addition to editing and publishing, Abigail campaigned tirelessly for suffrage bills. She brought national suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony to Oregon for a lecture tour and eventually became vice president of Anthony's National Woman's Suffrage Association. Traveling throughout the Northwest, she averaged over 200 talks a year.

Abigail's work was never easy. Rheumatoid arthritis she blamed on the rigors of her childhood made travel painful. Hecklers spiced the crowds who heard her speak. In Jacksonville, she was egged and burned in effigy. Her own brother, Harvey Scott, the Oregonian's powerful editor, opposed her work.

Through it all, Abigail's will and sense of purpose never flagged. Nor did the sharpness of her tongue. She denounced her brother's opposition as an outgrowth of the unfair privilege he had enjoyed since being born, simply because he was male. The hecklers she answered word-for-word. About the egg that landed on her head, she told her readers it had "saved a shampooing bill."(3)

By the time Abigail stitched the quilt in 1900—to enter in a national suffrage bazaar as a tongue-in-cheek example of Oregon women's accomplishments—she was a Northwest institution, but she had not reached her goal. Though women had secured the vote in Idaho in 1896, they were still denied it in Washington and Oregon. So Abigail pressed on. "Success will seldom come in the ways that one has planned for it," she wrote, "but come it will, sooner or later, to all who are faithful."(4)

Ten more years would pass before Washington let women vote. Abigail would have to wait another six to vote herself. In 1912, she became the first woman to register to vote in Oregon and the first woman in any state to write a suffrage proclamation in her own hand. In 1914, she finally cast a ballot, just months before she died at 80 years old.

At her death, men and women lauded Abigail Scott Duniway for her great accomplishments—her editing and publishing (including 21 novels), her national work on women's issues, her leadership of the Northwest fight for women's rights. More remarkable than these, however, were the will and strength of character that flowered in her long before she had a cause to lead.

"I can still 'see' her as she was," her sister Harriet wrote, "a slight young girl, evenings after the weary stretches of travel with that old book in her lap—sitting by the tent—or perchance one of the wagon wheels—or sitting on the ground—while our father was giving her commands to lay the Diary correct!—she was too weary at times to write—But always did her best." (5)

© Michael McGregor, 2003

Notes:

Abigail Scott Duniway, The New Northwest, July 15, 1880.

Quoted (without noting source) by Ruth Barnes Moynihan, Rebel for Rights: Abigail Scott Duniway (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press), 2.

Abigail Scott Duniway, The New Northwest, July 17, 1879.

Abigail Scott Duniway, Path Breaking: An Autobiographical History of the Equal Suffrage Movement in Pacific Coast States, 2nd Edition (New York, N.Y.: Schocken Books), 13.

Quoted in Mary Bywater Cross's Treasures in the Trunk: Quilts of the Oregon Trail, p. 85