Written by Michael N. McGregor

At 240 N. Broadway in Portland, a stone's throw from The Rose Garden where the Trail Blazers play their home games, a worn brick building stands alone, a forlorn island in a sea of traffic. Today it houses a plastics company, but in its heyday half a century ago it was Portland's premier jazz venue, the Dude Ranch. And on the night of December 5, 1945, it was the site of what may have been the greatest jazz jam in Portland history.

In those days, there was no Rose Quarter or Memorial Coliseum, no I-5 freeway separating Portland's near eastside from the Willamette River. The area where these stand now was a neighborhood of mostly aging buildings that formed the heart of Portland's African-American community. Running through the midst of it was N. Williams Avenue, a living artery of dancing, gambling and, most significantly, live jazz that pulsed and beat throughout the night.

People came from all around the Portland area—sometimes all the way from Idaho or even California when certain musicians were playing—to the nightclubs clustered around Williams Avenue: Paul's Paradise, the Frat Hall, the Savoy, Lil' Sandy's, Jackie's, and especially the Dude Ranch. Locals called the Dude Ranch "the club of startling surprises" because its owners, Sherman Pickett and (?) Patterson, known simply and affectionately as "Pic and Pat," seemed capable of booking anybody.

A reporter for The Observer, Portland's African-American newspaper, wrote in 1945, "Give ‘Pic & Pat" time and you'll see ‘em all." But though Lionel Hampton, Art Tatum and the Nat "King" Cole Trio appeared in later days, no night ever equaled that night in December of 1945 when Norman Granz brought his touring jam session, "Jazz at the Philharmonic," to town. That night legendary saxophonist Coleman Hawkins led a group that included trombonist Roy Eldridge, bassist Al McKibbon and a 25-year-old pianist with "a lightning-like right hand" who was soon to usher in the bebop age, Thelonious Monk.

"Never before in the history of the northwest has there been so much jazz music played per square minute by any group," The Observer proclaimed. Portland jazz historian Bob Dietsche has suggested that for some "it was the beginning of modern jazz in Portland."

In a long article on the Dude Ranch published in the magazine Open Spaces in 1999, Dietsche wrote:

"It was the Cotton Club, the Apollo Theatre, Las Vegas and the wild west rolled into one. It was a shooting star in the history of Portland entertainment—a meteor bursting with the greatest array of black and tan talent this town has ever seen. Strippers (called shake dancers then), ventriloquists, comics, jugglers, torch singers, world renowned tap dancers like Teddy Hale and, of course, the very best in Jazz."

Countless local jazz musicians walked away from Dude Ranch shows with new energy and new ideas for their own music, especially on that night when Hawkins blew his tenor sax and Monk played what Dietsche calls "bizarre chords [that] had some people laughing and others, like Eldridge, grinding their teeth." Among those Monk inspired to take jazz further were Quincy Jones trumpeter Floyd Standifer and pianist Leo Amadee, who had a strong influence on the development of jazz piano in Portland.

The Dude Ranch lasted at its North Broadway location only about a year before a shooting prompted Portland authorities to close it down. It reopened a few blocks away but never again reached the heights it had during that brief time in 1945-46.

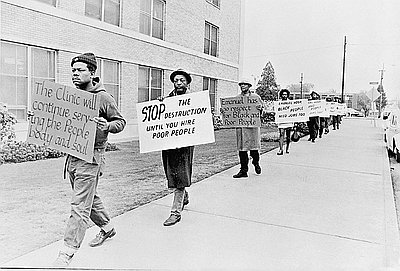

Jazz was popular in Portland as early as the 1930s but it flourished after World War II, mostly because the need for workers in the shipbuilding industry during the war significantly increased Portland's African-American population. Former war-industry and railroad workers who were unable to secure loans from local banks saved their money and opened small businesses—groceries, dry cleaners, night clubs, etc.—in the area around Williams Avenue, making it the focal point of the African-American community.

Overcrowding in the area after the war, caused primarily by hostility to African-American settlement in other parts of Portland, put more people on the streets, day and night, prompting the clubs around Williams Avenue to stay open around the clock. Soon nationally prominent musicians were stopping in Portland on their way to other places, sometimes playing impromptu jams in the homes of friends for fun.

Many young people in the area hung out at a pool hall run by Ed Slaughter, who played the latest jazz on a jukebox he called "canned ham" and taught them how to listen to it. Some of these young people, like Dietsche and KMHD jazz deejay—and former Portland city commissioner—Dick Bogle, became the jazz connoisseurs for the next generation.

When the night clubs disappeared, Ed Slaughter's pool hall went with them, as did the all-night restaurants offering homemade chili or barbeque and the crowds of people dressed in their very best who brought such life to what Dietsche remembers fondly as an area "that never slept."

"Among the well-dressed shipbuilders, maids and Pullman porters," he wrote in Open Spaces, describing those who frequented the Dude Ranch in its heyday, "were Busy Siegel-like characters in sharkskin suits and broad Panama hats, in from St. Louis for a friendly game of cards or dice on the second floor. There were pin-striped politicians with neon ties, Hollywood celebrities and glamour queens in jungle red nail polish and leopard coats, feathered call girls and pimps in fake alligator shoes, zootsuited hipsters and side-men from Jantzen Beach looking to get ‘the taste of Guy Lombardo out of their mouths,' Nobel prize candidates and petty thieves, Peggy Lee's ‘Big Spender' and Norman Mailer's ‘White Negro,' racially mixed party people, dancing and exchanging attitudes, who could care less that what they were doing was on the cutting edge of integration in a city called ‘the most segregated north of the Mason-Dixon line.'"

Jazz still thrives in Portland, at clubs such as Jimmie Mak's, Brasserie Montmartre, and The Blue Monk on Belmont, but the scene is much smaller than it once was and more diffused. Jazz greats still pass through town but, more often than not, they play in venues such as Memorial Coliseum or the Rose Garden—the far-less-intimate monuments to late-20th century " urban renewal" that replaced the once-hopping clubs along Williams Avenue.

© Michael McGregor, 2004

Michael McGregor is Associate Professor of Non-fiction writing and English at Portland State University.