Depression and the New Deal

Though Portland’s population grew steadily through the late 1920s, economic opportunities slowed. Prices for timber and wheat, the mainstay of the local economy, started to decline in 1926. The collapse of the stock market in late 1929 only highlighted a precipitous 50 percent decline of residential construction for the year, which typified the turn of economic conditions along the Pacific Coast. The Chamber of Commerce hoped that street-widening projects, sewer construction, and dock repair work might create jobs. By 1931, however, Sullivan’s Gulch, below the Union Pacific Railroad tracks between Northeast Twelfth and Northeast Twentieth Streets, had its own Hooverville to shelter the unemployed. In 1931, when Portland’s sixth largest bank, Hibernia, closed its doors because its officers lost deposits in stock market investments, the conservatively run U.S. National Bank and First National Bank both faced runs on their accounts by panicky depositors.

As unemployment deepened, people resorted to traditional sources of relief. In the early 1920s, local charitable agencies had centralized fundraising through a Community Chest, whose proceeds were distributed to agencies like the Red Cross, hospitals, orphanages, homes for the elderly and the disabled. During the early years of the Depression, charity organizations like the Community Chest provided emergency funds for the unemployed and their families, and the city and county joined them to raise and distribute funds, usually through an emergency committee headed by prominent businessmen. Cities like Portland raised new money for work relief by selling bonds, which were purchased by local banks.

By 1932, homeowners feared that declining income would force them to default on mortgage payments, so they pressured city governments to lower both property taxes and city budgets. Mayor George Baker dismissed pleas by health authorities and fishermen for the city to build sewage disposal plants to free the Willamette River from pollution, because he believed citizens would not accept the costs. Leslie Scott, the state highway commissioner, proposed a sales tax, which the legislature refused to consider. With passage in 1933 of the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition, the legislature made the sale of liquor a state monopoly and declared both the profits and tax revenues to be the state’s matching funds, so that Oregon might receive federal relief grants. By 1934, private charities and local governments could return to their former role of assisting those unable to work.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt became president in March 1933, the New Deal reorganized production so that firms could make profits and empowered workers to organize for collective bargaining to increase wages. In Portland, a new relationship between workers and employers was worked out on the waterfront. To pressure shippers on the West Coast to engage in collective bargaining, the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA), with headquarters in San Francisco, planned a strike for all major waterfronts in the spring of 1934. The business elite, as well as stevedoring firms, believed that the president of the ILA, Harry Bridges, was a Communist and was preparing to “seize power.” The ILA’s goals, however, were more modest: union recognition as bargaining agent, union control of the hiring hall that assigned workers to jobs, reduction of the normal work day to spread work around, and higher wages.

After a bloody clash in San Francisco, California’s governor sent in the national guard, and labor unions called a general strike that closed the waterfront. In Portland, a process of mediation began in July 1934 under considerable pressure, because President Roosevelt was scheduled to arrive in August to dedicate the Bonneville Dam construction site. Governor Julius Meier refused to send the National Guard to forestall clashes similar to those in San Francisco, so the major stevedoring firms agreed to arbitration by the federal National Longshoreman’s Board. After a compromise that recognized the ILA as bargaining agent with control over the hiring halls, the strike was ended.

By 1935, the New Deal consolidated relief efforts through a new agency, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which intended to employ skilled workers, writers, artists, and actors on a engineering and service projects. In Portland, E.J. Griffith, a former timber broker and loyal Democratic fundraiser, put 25,000 people to work for the next seven years. His projects maximized employment and minimized the outlay for capital goods, like machinery. Portland had projects for writers, artists, and actors, as well as a Women’s Division that emphasized household crafts. The largest engineering projects were Rocky Butte Scenic Drive in the northeast corner of the city, and the beginnings of a new airport on the Columbia River. In conjunction with the Oregon Highway Department, the WPA built Wolf Creek and Wilson River highways to the Oregon Coast. Skilled iron workers were employed in a workshop on Boise Street to make doors, door handles, keyholes, and other artifacts for Timberline Lodge, a WPA project on Mt. Hood, as well as the decorative iron gates for the University of Oregon Library. Mayor Carson, however, complained that the projects deprived the city’s inhabitants of self-reliance, and urged Portland voters to reject a Public Housing Authority, which he labeled “socialistic.”

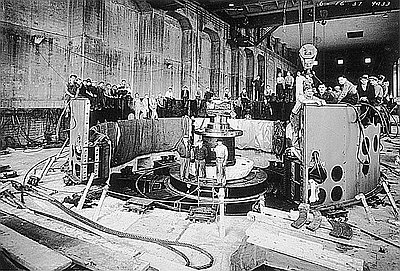

President Roosevelt wanted the federal government to build dams on the Columbia River to rejuvenate the regional economy, while Oregon’s influential Republican senator Charles L. McNary saw the vast construction project as the source of necessary jobs. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, in charge of large building projects through the Public Works Administration (PWA), distributed funds to the states to relieve unemployment, so that allocating huge sums for Bonneville meant foregoing smaller projects in Portland. Because Mayor Carson provided little leadership, Senator McNary’s priorities prevailed.

To distribute the power produced by dams on the Columbia, a compromise was reached between Governor Julius Meier, who advocated the sale of power to new publicly owned utility districts, and PGE, which wanted power sold cheaply to private companies. The compromise was embodied in the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), a government agency that would sell power produced at the Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams to both public utility districts and private power companies. The ALCOA and Reynolds aluminum companies also got contracts with the BPA for inexpensive electricity to fuel their factories.

© William Toll, 2003. Updated and revised by OHP staff, 2014.

Sections

Related Historical Records

Bonneville Dam Workers Assembling Turbine

In 1937, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) completed construction of Bonneville Dam, located forty-two miles east of Portland on the Columbia River. The dam’s turbines, connected …

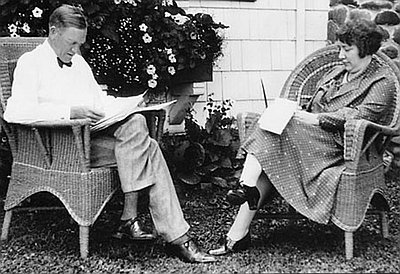

Charles L. McNary (1874-1944)

This photograph shows Senator Charles L. McNary with his secretary in 1932. Charles Linza McNary was not considered much of a campaigner. He gave one or two speeches …

Mt. Hood Timberline Lodge History

This is the front page of a history of Mt. Hood’s Timberline Lodge, written by Portland area writer and teacher Claire Warner Churchill. Churchill was a field supervisor …