- Catalog No. —

- OHS SIF 1131-B

- Date —

- c. 1900

- Era —

- 1881-1920 (Industrialization and Progressive Reform)

- Themes —

- Geography and Places, Labor, Trade, Business, Industry, and the Economy, Women

- Credits —

- Oregon Historical Society

- Regions —

- Portland Metropolitan

- Author —

- Unknown

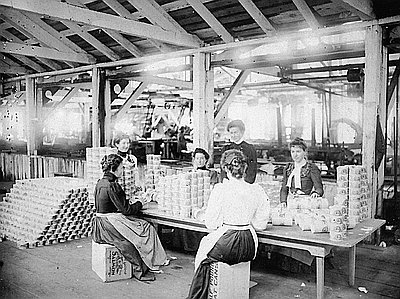

Women Workers, Pacific Coast Biscuit Company

This photograph of three women packers at the Pacific Coast Biscuit Company was probably taken sometime between 1900 and 1905. The Pacific Coast Biscuit Company operated plants in Portland that manufactured cookies, crackers, candy, and macaroni. The photograph offers a glimpse into the working conditions experienced by women working in factory settings in turn-of-the-century Portland.

In 1900, very few Oregon women worked outside of the home--just over thirteen percent compared to the national figure of twenty percent. More women, twenty-five percent of the female population, worked for wages in Portland than elsewhere in the state. Although the majority worked as domestic help or as personal servants, the second largest group, nearly twenty percent of Portland’s female laborers, worked in mercantile & manufacturing industries. At the turn of the twentieth century, work formerly done in the home increasingly moved into factories. Women in urban areas found factory work sewing, laundering, baking, and fruit and vegetable canning, for example.

A growing female workforce prompted some citizens to seek legislation to limit hours and to improve conditions. Some labor advocates viewed such legislation as the first step in acquiring similar protection for all workers, male or female. Other social reformers sought protective legislation for women as a way to ensure the health of mothers. In 1903, the Oregon State Legislature enacted a statute that limited to ten the number of hours mechanical establishment, factory, or laundry employers could ask their female employees to work. The statute also required the employers to provide seats for female employees to use during breaks.

The limited scope of the bill helped it to pass a legislature with few labor-sympathetic politicians. It did not apply to the majority of female laborers in Oregon, as it excluded agricultural work, teaching or professional work, and domestic or personal service work. Consequently, the bill had not posed much of a threat to legislators from rural areas. The increasing visibility of women wage earners in factory settings helped legislators from Multnomah County push the bill through. “Perhaps you not from Multnomah County are not accustomed to seeing girls standing for 12 to 14 hours a day,” stated House Representative Banks, making his case for the law.

Despite its limited scope when enacted, the law went on to have a significant effect on constitutional history when it withstood the Supreme Court’s scrutiny in Muller v. Oregon (1908).

Further Reading:

Johnson, Elaine Zahnd. “Protective Legislation and Women’s Work: Oregon’s Ten-Hour Law and the Muller v. Oregon Case.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oregon, 1982.

Written by Sara Paulson, © Oregon Historical Society, 2007.

Related Historical Records

-

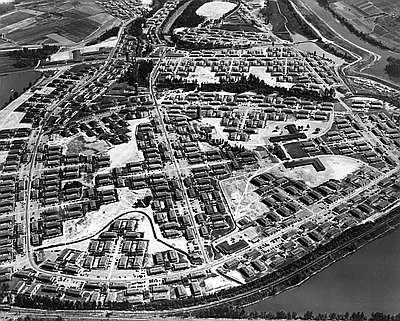

African American and Women Workers in World War II

Wartime conditions severely disrupted rural communities, creating dire labor shortages in agricultural and natural resource industries like logging and lumbering. Thousands of Oregonians left farms, ranches, and logging …

-

Women Cannery Workers

This photograph was taken by Portland photographer John F. Ford, probably between 1900 and 1902. It shows women labeling cans of salmon at the Megler Cannery in Brookfield, …